ENB Pub Note: This is a fantastic article from the Merchant’s News Substack by Giacomo Prandelli. We highly recommend subscribing to and reading his Substack. Stu Turley just had an interview with Giacomo, and the podcast is in production for release soon. We will keep you posted.

Everyone’s celebrating gold breaking $4,200 and silver doubling to $62 but they’re completely ignoring the setup forming in oil markets.

The best trades, in commodity cycles, aren’t the ones everyone’s already piled into. They’re the ones where the fundamentals are telling us one thing while the market’s pricing in the exact opposite.

Right now, in my view oil is that trade.

This year has been absolutely extraordinary for metals.

Gold surged 56% to north of $4,200 per ounce.

Silver? Try a 100%+ rally pushing past $61.

Copper climbed 35% toward $12,000 per metric ton.

For the first time in 45 years, all 3 metals hit record highs simultaneously.

The catalyst?

3 forces converging at once, and they’re all tied to the same mega-trend reshaping global commodity demand:

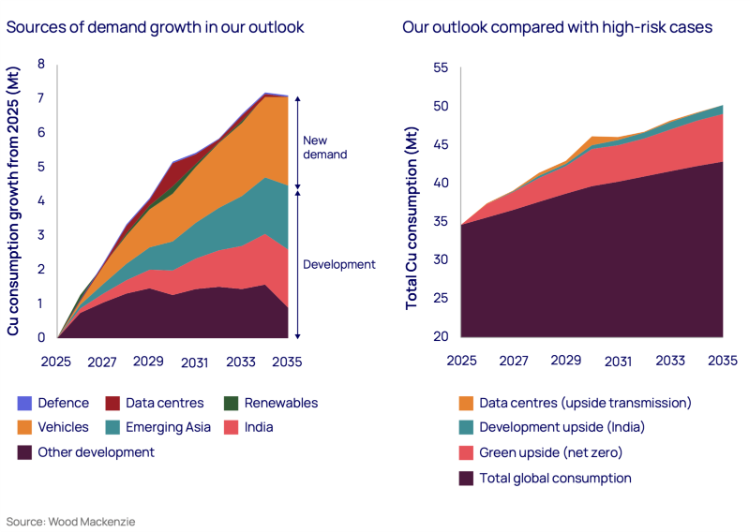

- artificial intelligence infrastructure is devouring physical materials at a staggering pace. When Microsoft built that $500 million data center in Chicago, they consumed 2,177 tonnes of copper that’s 27 tonnes per megawatt of power. A single Nvidia GB200 chip unit contains over 5,000 copper cables stretching more than 3.2 kilometers. The IEA projects data centers alone will consume 500,000 metric tons of copper annually by 2030. That’s 2% of global copper demand from an industry that barely existed a decade ago, stacked on top of surging requirements from EVs, wind turbines, and military applications.

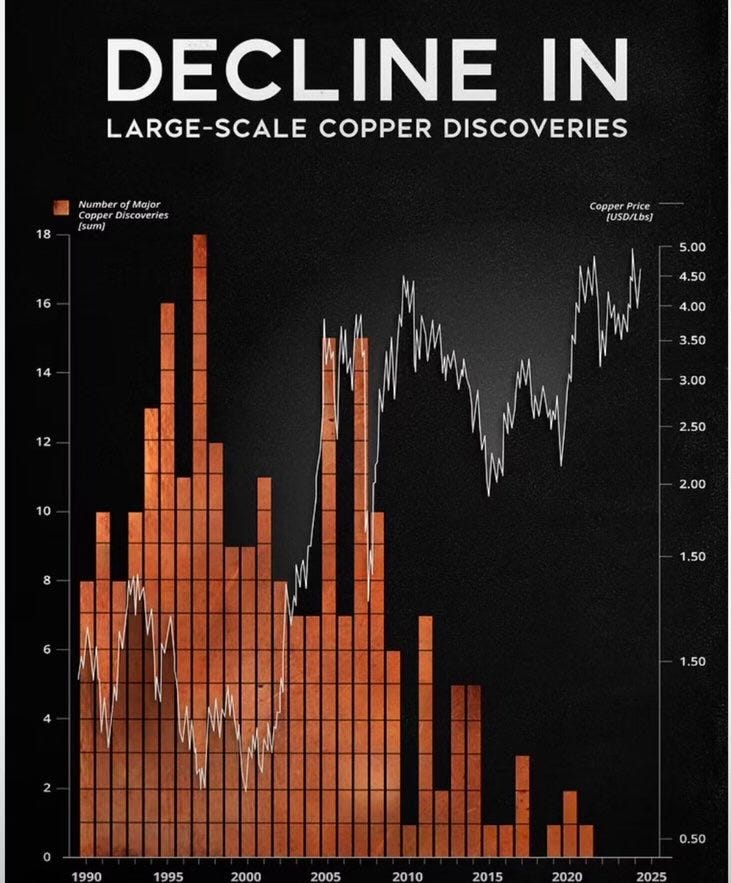

- supply can’t keep up. Copper markets are facing deficits of 124,000 tonnes in 2025 and 150,000 tonnes in 2026 according to Reuters analyst surveys. FreeportMcMoRan’s Grasberg operation in Indonesia hit challenges in September. Glencore downwardly revised their 2026 production forecasts. Mining isn’t like turning on a tap these constraints run deep into geology and processing capacity, and they can’t be fixed with a few quarters of elevated capex.

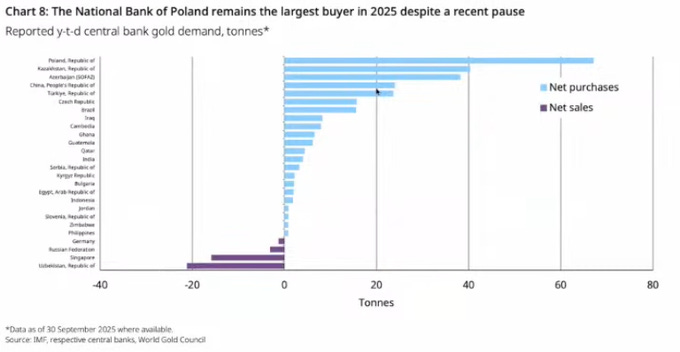

- tariff risks are triggering precautionary buying. US Commerce Secretary recommendations for 25% tariffs on refined copper imports have importers stockpiling like crazy. Central banks, particularly in emerging markets, have been persistent buyers of gold. Trade tensions and government debt concerns elevated safe-haven demand. The gold-silver ratio compressed from above 80:1 in November to roughly 68:1 by mid-December silver outperforming gold is a classic signal that the entire metals complex is on fire.

These aren’t temporary disruptions. AI infrastructure isn’t going away. Mining supply constraints take 8 years to resolve through new project development. Tariff uncertainty and geopolitical fragmentation are structural features.

The metals rally of 2025 is real, it’s justified, and it’s likely to persist.

Now Let me show you why the party happening in metals today is actually setting the stage for oil’s resurrection in 2026 and why the names positioning for this shift could deliver the kind of returns that make this year’s metal rallies look modest. (+ 💰 The Merchant’s Play)

Brent crude spent most of the year trapped between $60s per barrel.

The narrative? Massive oversupply.

The IEA revised their 2026 surplus estimate to 4 million barrels per day nearly 4% of global demand. OPEC+ accelerated production rollbacks, adding 335,000 barrels per day in July alone. The UAE is bringing 200,000 barrels per day of new capacity online annually through 2026. Goldman Sachs forecasts a final wave of supply surge pushing Brent to $56 in 2026 before recovering from 2027 onward.

Every analyst, every investment bank, every energy trader is looking at this data and concluding the same thing: oil’s going nowhere…

They’re wrong.

The critical error is that they’re confusing a short term supply glut with long term structural adequacy.

Yes, 2025 and most of 2026 will see inventory builds and weak prices. But this dynamic is masking something far more consequential major oil companies aren’t investing nearly enough capital to replace declining production from aging fields and meet rising demand beyond the next years.

Let me walk you through.

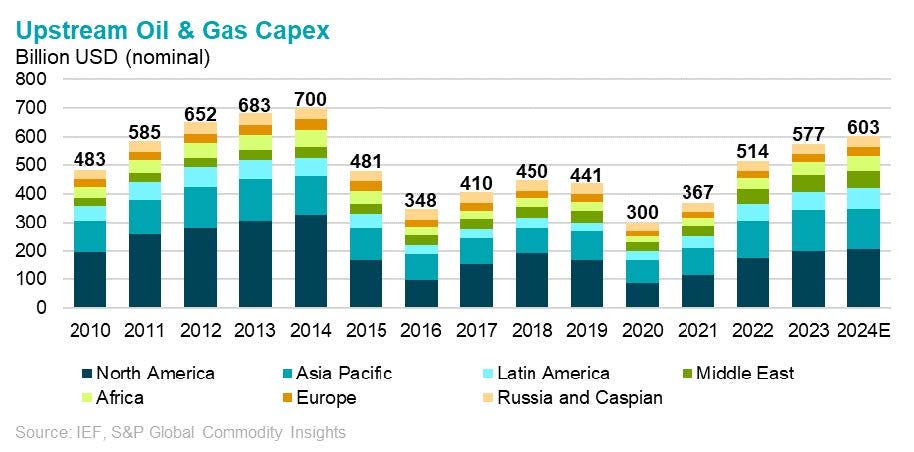

Global upstream oil and gas capex hit $514 billion in 2022 that’s $70 billion below the 2011 peak at the start of the shale boom.

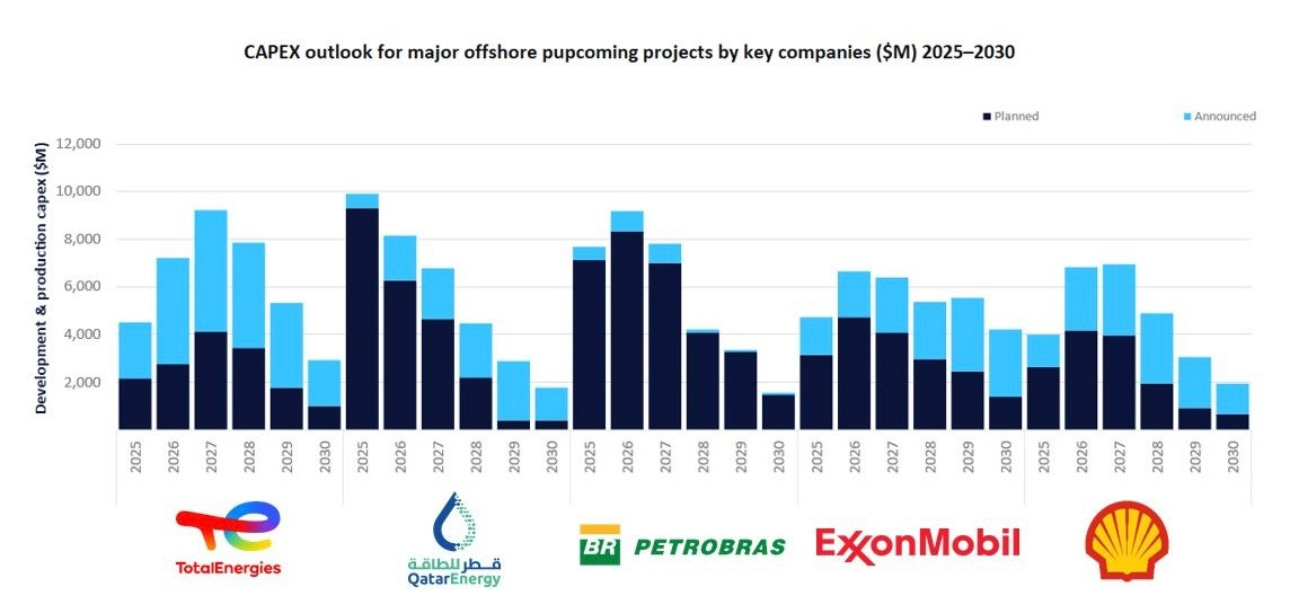

TotalEnergies announced capex cuts exceeding $1 billion annually starting in 2026, with overall guidance revised down to $16 billion for 2026 and $16 billion through 2030. BP boosted oil and gas investments to $10 billion, but that’s coming off years of underinvestment, and much of their portfolio sits above the cost curve. ExxonMobil’s guidance of $28 billion for 2026 is substantial, sure but it’s not enough to offset natural declines in existing fields and drive meaningful production growth.

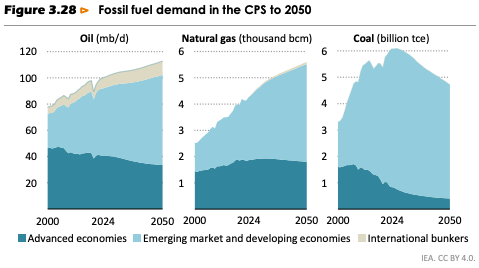

Meanwhile, demand keeps rising.

The IEA projects global oil demand increasing by 800,000 barrels per day in 2025 and another 900,000 barrels per day in 2026. OPEC’s even more bullish, revising their 2026 demand growth forecast to 1.4 million barrels per day.

If demand increases by 900,000 barrels per day in 2026 while production from existing fields declines by 1.5% annually due to natural depletion and that’s a conservative estimate given aging reservoir portfolios across major producing regions you get a supply deficit within some years. It’s not a question of if. It’s a question of when.

The industry can’t sustainably operate in deficit mode. Inventory draws become exhausted. Spare production capacity fills. And prices must rise to equilibrate supply and demand.

Goldman Sachs explicitly projects the market shifting to a supply deficit in the second half of 2027, with Brent recovering to $70+ by 2027 and potentially $80 by end 2028. Their reasoning? Low 2026 prices will depress non-OPEC supply while demand continues advancing steadily.

But here’s the insight that separates this thesis from consensus: 2026’s depressed prices are the catalyst for the next cycle.

When prices fall toward $56 per barrel, non-OPEC producers particularly small and mid cap operators dependent on positive cash flows constrain capital investment and defer production growth projects. The IEA itself notes that at lower price levels, producers lack investment incentives to develop the long cycle projects required to offset natural declines.

This creates a self-reinforcing dynamic:

low prices suppress investment → investment suppression reduces future supply growth → reduced supply growth eventually necessitates higher prices to clear markets.

Ask yourself this question: if major integrated oil companies and national oil companies are limiting capex to 2015-2018 levels while demand is rising, where will incremental oil production come from in 2027 and beyond?

💡 It won’t, absent substantial price appreciation that justifies additional investment.

Global hydrocarbon production, excluding OPEC members with low-cost expansions in the Middle East, faces production declines of 2-4% annually from existing fields as reservoirs mature. Only new project startups and OPEC+ capacity expansions can offset these declines and meet incremental demand.

The problem? New project sanctioning has collapsed. Companies aren’t approving sufficient major greenfield developments to fill the supply gap emerging in 2027.

Increasing supply to maximize revenue might be the optimal strategy for an oil-producing country. This heightens the risk of another market reset occurring somewhere between in 2026.

A market reset.

That’s Wall Street speak for prices are going to get crushed, then they’re going to explode.

💰The Merchant’s Play:

So how do you play this?

You focus on companies with 2 characteristics:

- low cost production profiles that generate cash flow even when prices compress in 2025-2026,

- combined with strategic growth assets that will ramp production end 2026 precisely when supply constraints become the market’s dominant driver.

2 names stand out based on their unique positioning in the supply constrained market ahead.

ExxonMobil:

ExxonMobil represents the most compelling growth story in global upstream oil and gas, and it’s all about timing.

The company’s Guyana operations are genuinely transformational. Total production capacity is expected to reach 1.7 million barrels per day by 2030, growing from approximately 616,000 barrels per day in 2024. The Yellowtail, Uaru, Whiptail, Hammerhead, and Longtail projects will deliver incremental production ramps between 2025 and 2030, with Yellowtail beginning operations imminently upon arrival of its FPSO vessel from Singapore.

This production cadence is critical ExxonMobil will be adding meaningful volumes precisely when the market transitions from oversupply to deficit, positioning the company to capture premium pricing on incremental barrels.

Beyond Guyana, ExxonMobil is doubling Permian Basin production to approximately 2.3 million barrels of oil equivalent per day by 2030. The Permian expansion provides flexible, short cycle production that can be ramped or decelerated based on price signals critical optionality in a volatile market environment.

With capex guidance of $28 billion annually through 2030, ExxonMobil is the largest single capital deployer in the global oil and gas industry. Their combined Guyana Permian production growth will deliver over 3 million barrels of additional production capacity through 2030 that’s roughly 3% of global demand growth, a substantial share of the incremental barrels required to fill the supply gap opening in 2027.

At oil prices recovering toward $75 per barrel this production growth translates directly to earnings per share expansion and enhanced shareholder distributions. The company’s committed to a 4% annual progressive dividend while maintaining share buyback capacity even at lower oil prices. You get paid to wait, then you get paid again when the thesis plays out.

Shell:

Shell offers a more balanced profile combining LNG growth, liquids stability, and exceptional cash returns.

The company’s targeting 5% annual LNG sales growth through 2030, with current sales capacity of 66 million tons annually positioned to expand materially as existing projects ramp and new capacity additions achieve first gas. Shell sold 66 million tons of LNG in 2024 they’re the largest single trader in the world.

More critically for the 2026-2027 thesis, Shell’s targeting over 1% annual upstream production growth through 2030 while maintaining liquids production at 1.4 million barrels per day. That’s an explicit commitment to production stability despite capital discipline.

The Dragon field development in Venezuela is the timing asset everyone’s overlooking. Shell’s expediting Dragon’s development to achieve first gas in 2026 one year ahead of schedule with production anticipated to support Trinidad’s Atlantic LNG facility and provide supply for Shell’s global LNG business. This timing aligns precisely with the supply constrained period of 2027, when LNG prices are expected to elevate amid global demand growth and tight natural gas supply.

What distinguishes Shell is the structural cost advantage the company’s targeting over 1 million barrels per day of additional production capacity through 2030 at an average breakeven cost of $35 per barrel. That means Shell’s production is among the lowest-cost in the industry and will generate exceptional returns across a wide range of price scenarios. Combined with $6 billion in cumulative OPEX reductions achieved by 2028, Shell’s positioned to generate sector leading free cash flow during both low-price and recovery periods.

Shell has reduced capex guidance to $21 billion annually for 2025-2028, representing disciplined capital allocation focused on high return projects in LNG, deep water oils.

Here’s how I’m thinking about this trade:

Phase 1 (2026): Compressed price environment eliminates marginal producers but benefits low cost operators through free cash flow generation and dividend growth. Both ExxonMobil and Shell generate substantial cash even at low $60 Brent. You get paid solid dividends while everyone else is panicking about the oil glut.

Phase 2 (2026-2027): Growth capital deployed in Guyana, the Permian, Dragon LNG, and low cost projects triggers earnings growth precisely when price recovery materializes. Both companies have committed to production growth when supply demand fundamentals require incremental barrels to clear markets.

Phase 3 (2028+): The supply deficit that Goldman and others are forecasting becomes the market’s reality. Prices potentially push toward $80+ per barrel, and both companies are producing materially more oil and gas than they are today at higher prices.

This contrasts sharply with market expectations of perpetually weak oil markets. The market’s priced in ongoing oversupply well into the 2030s despite overwhelming structural evidence to the contrary.

ExxonMobil offers the more aggressive growth profile with Guyana production scaling to transformational levels this is the play if you want maximum exposure to the supply recovery thesis. Shell provides the more balanced profile combining LNG growth, liquids stability, and exceptional cash returns this is the play if you want income plus upside optionality.

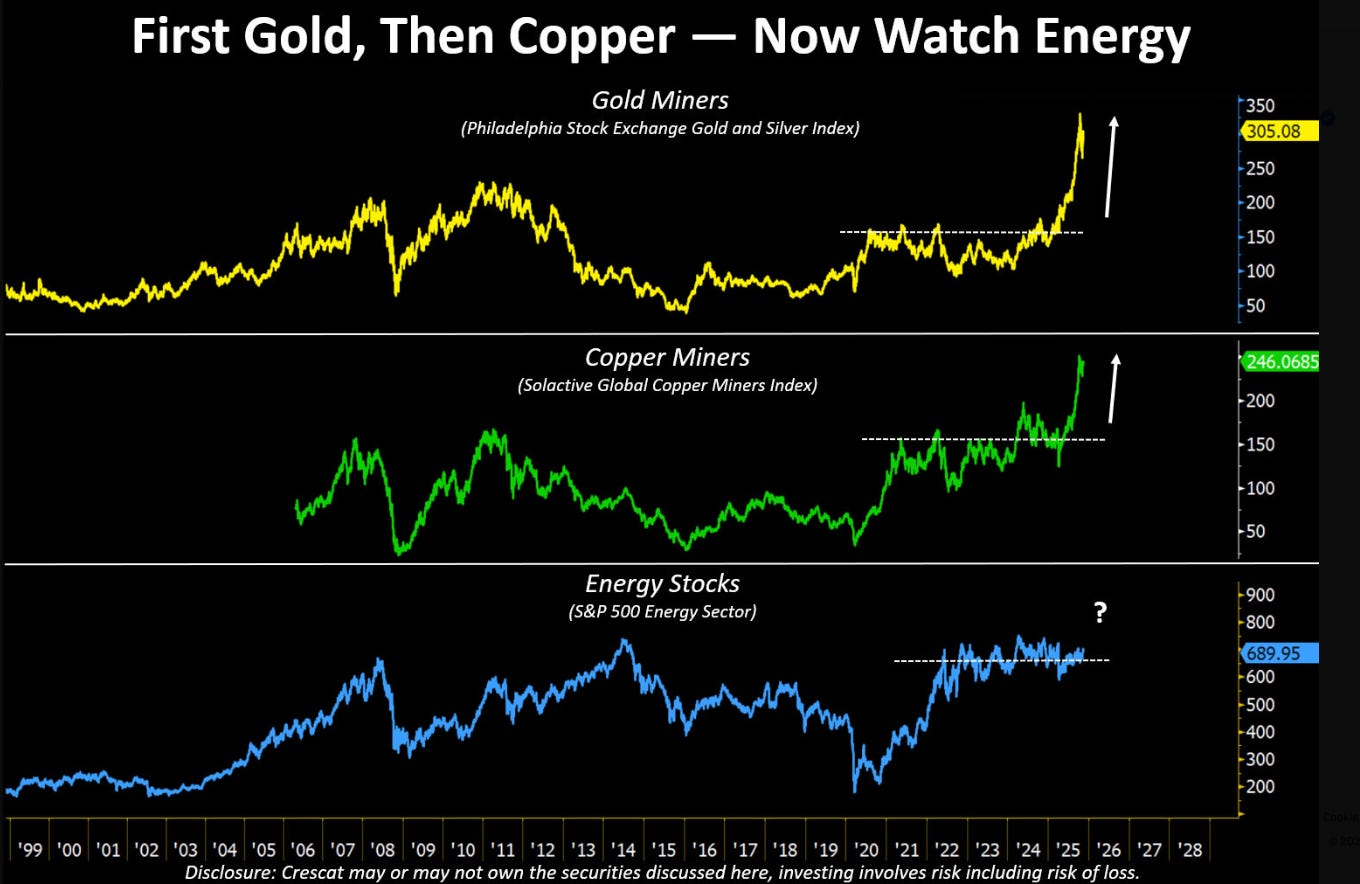

Remember how we started this conversation? Metals rallied in 2025 because AI infrastructure created structural demand that supply couldn’t meet, amplified by mining disruptions and tariff uncertainty.

Oil’s about to follow the exact same playbook, just on a delayed timeline.

Structural demand growth? Check 900,000 to 1.4 million barrels per day annually.

Supply constraints? Check capex discipline and underinvestment in long cycle projects.

The catalyst for higher prices? Check 2026’s low prices will suppress the very investment needed to meet 2027-2028 demand.

The metals rally of 2025 isn’t just a parallel story to oil it’s a preview. When physical supply can’t meet structural demand, prices adjust violently. We’ve seen it in gold, silver, and copper this year.

We’re about to see it in oil next year.

The best part? While everyone’s chasing metals at all time highs, oil’s sitting unloved at multi year lows. The setup is perfect. The timing is everything. And the names positioned to capitalize offer both downside protection through their low cost structures and meaningful upside leverage to the supply recovery that’s coming.

This is about recognizing that the structural forces driving today’s metal rally are about to drive tomorrow’s oil rally and positioning in the names that will capture that transition.

The divergence between metals and oil in 2025 will likely reverse in 2026-2027 as the supply demand dynamics flip. The market’s making the classic mistake of extrapolating the present into the future indefinitely.

Don’t make that same mistake.

Be the first to comment