ENB Pub Note: This is an outstanding article from the Energy Bad Boys Substack. Isaac Orr and Mitch Rolling are in the National Treasure status. This is an outstanding article, and we highly recommend subscribing to their Substack. We will see about getting them back on the Energy News Beat Podcast to discuss this and other articles.

Most public discussions about solar focus on energy production, but power systems are built around reliability during peak demand. Once you look at the grid through the lens of accredited capacity—that is, capacity that can be relied upon during peak demand—instead of annual energy, the land requirements for different technologies look radically different.

This is the energy vs. capacity distinction that most solar land-use debates miss.

Last September, we were retained by Cerro Gordo County, Iowa, to provide expert witness testimony on a proposed 500-megawatt (MW) solar facility, the River City Energy Project. If you are interested in retaining us for a utility proceeding, please reach out to us by clicking here.

As part of the proceedings in the Generating Certificate Utility (GCU) docket GCU-2025-0004, we were responsible for evaluating the land-use and economic impacts of solar in Cerro Gordo County and how it would compare to a new combined-cycle (CC) natural gas (CC) facility.

For today’s analysis, we’ll focus on the land-use impacts of solar; they are worse than you think.

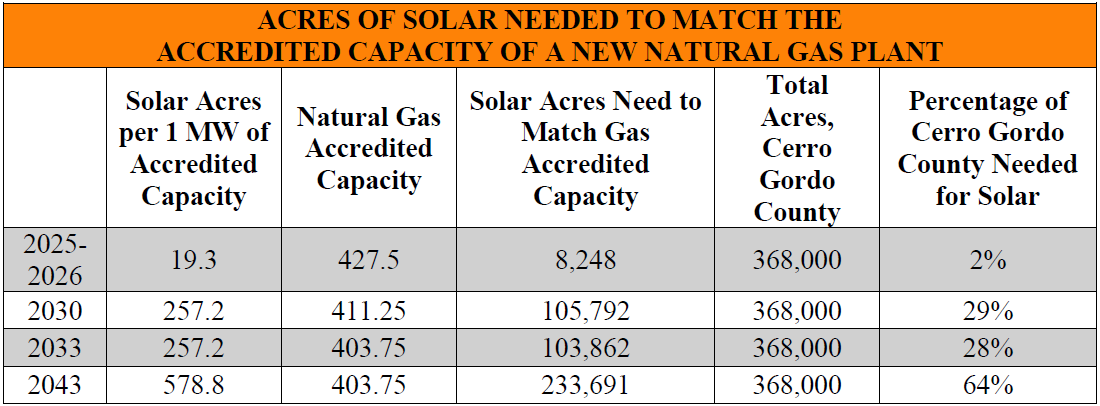

Long story short, matching the accredited capacity of one natural gas plant sitting on 58 acres of land with solar in 2030 would require over 105,792 acres of solar panels, roughly 29% of the total land area of Cerro Gordo County.

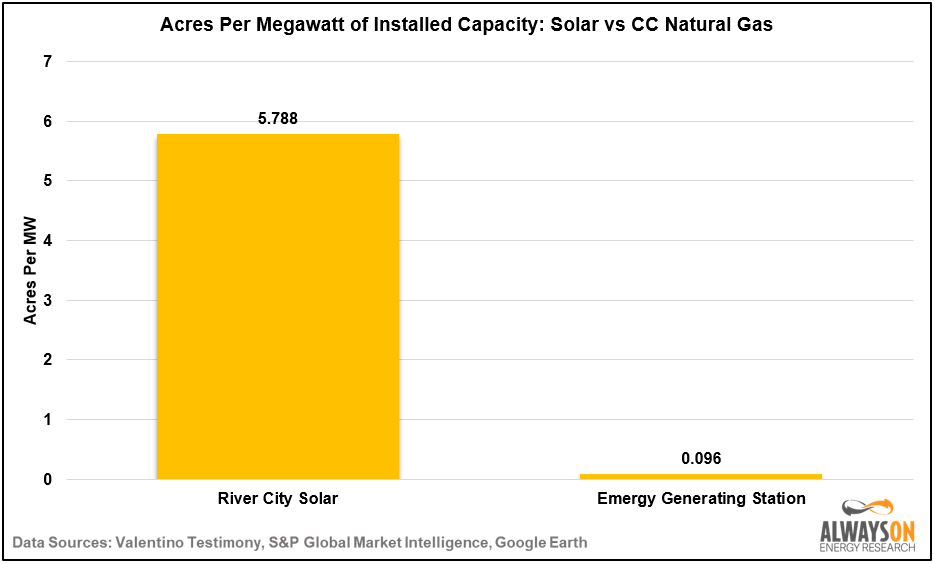

In contrast, the Emery Generating Station, a nearby CC natural gas plant also located in Cerro Gordo County, has a total rated capacity of 602.8 MW and sits on a total of around 58 acres. Including the power plant and the parking lot, land use for this CC plant equates to 0.096 acres per MW of installed capacity.

This means the proposed Ranger Power solar facility would require 60 times more land per MW than a CC natural gas plant of equal size.

The disparities in land use become more evident when the reliability and resource adequacy attributes of each resource are considered.

Today’s Key Word is Capacity Value. Do You Have Any?

In testimony in favor of the proposed solar project, River City Witness Waylon Brown stated the Ranger Power project is expected to garner a “about 50 percent capacity credit in spring, summer, and fall,” from the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (“MISO”).

However, Mr. Brown’s stated values are not at all reflective of the projected capacity values that will be attributed to wind and solar in the coming years because MISO is revising its capacity accreditation methods to better reflect the reliability contributions of all resources on its system during periods where the system is most likely to experience loss of load hours.

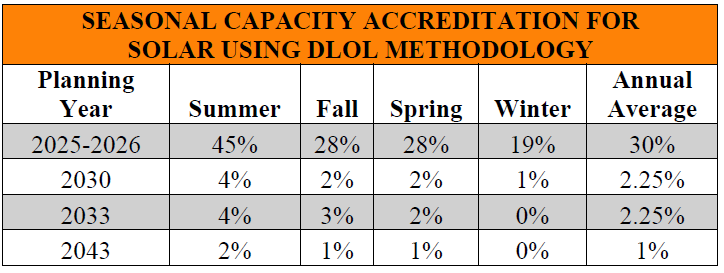

The shift away from Effective Load Carrying Capacity (“ELCC”) to Direct Loss of Load (“DLOL”) accreditation will have important implications for the reliability metrics assessed for each resource class.

Table 1 shows the indicative seasonal capacity accreditations that solar facilities would receive in the 2025-2026 planning year using DLOL, and the DLOL assumptions used in 2030, 2033, and 2043 in the MISO 2024 Regional Resource Assessment and Technical Appendix.

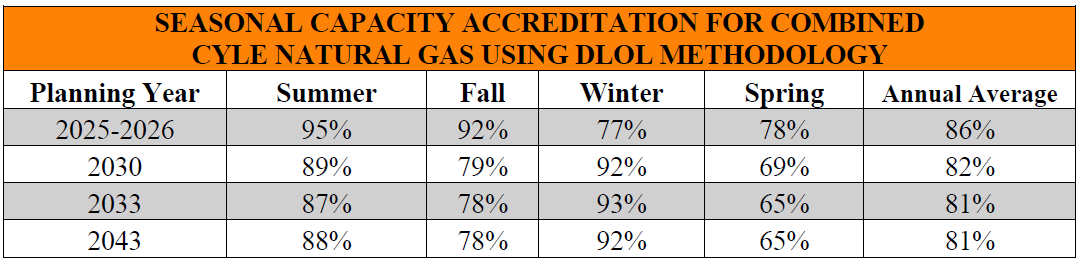

MISO documents also show the projected capacity accreditations of combined cycle natural gas facilities using DLOL during the same period. Annual average capacity accreditations are expected to be 86% in the 2025-2026 Planning Year, 82% in 2030, 81% in 2033, and 81% in 2043 (See Table 2).

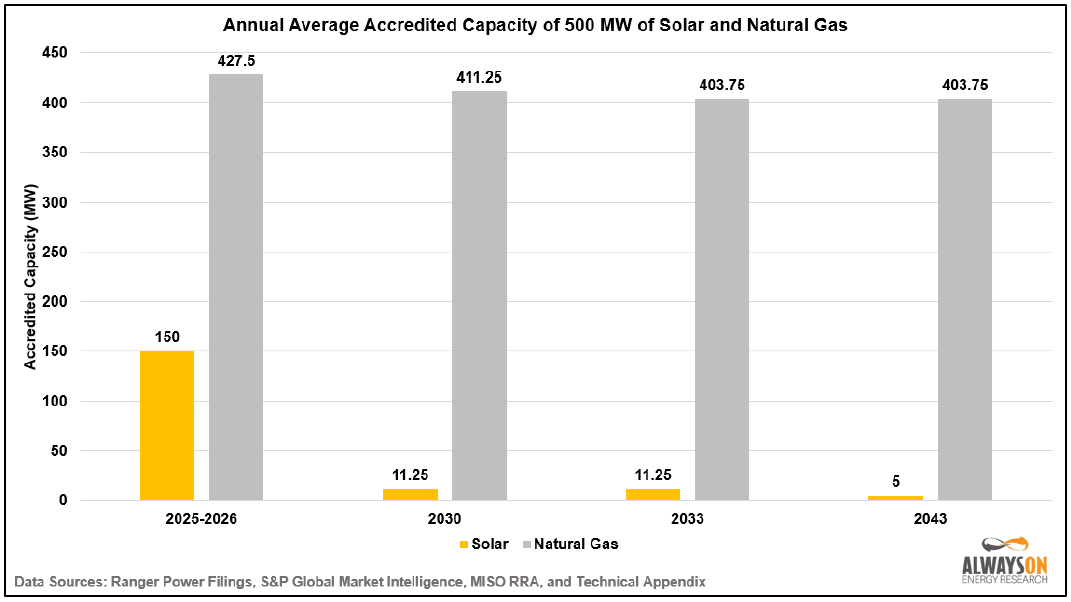

Comparing the proposed Ranger Power project with a new 500 MW combined cycle natural gas facility yields substantial differences in the accredited capacity awarded to each 500 MW facility. Figure 2 adjusts the total installed capacity of each resource by its annual average capacity value to determine the annual average accredited capacity each project would provide to the MISO system.

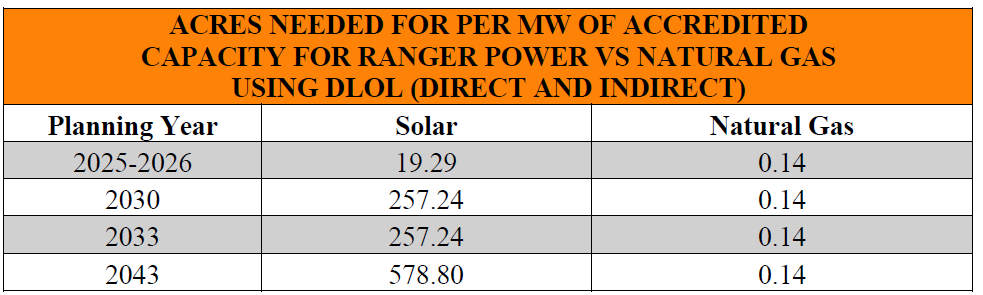

By dividing the total acreage of the proposed Ranger Power project and a new natural gas plant by its accredited capacity from Figure 2, we can determine the number of acres needed to provide one MW of firm accredited capacity to the MISO system in each Planning Year, shown in Table 3.

The low capacity value attributed to solar using the DLOL metric would necessitate 19.29 acres of solar panels for one MW of accredited capacity in the 2025-2026 planning year, compared to 0.14 acres for a combined cycle natural gas plant. In 2030 and 2033, it would require 257.24 acres of solar panels for one MW of accredited capacity, growing to 578.80 acres in 2043.

In comparison, natural gas would require 0.14 acres, 0.14, and 0.14 acres in 2030, 2033, and 2043, respectively.

In the interest of maximizing the efficiency of land used for electricity generation, it is illustrative to compare the acreage needed to provide the same capacity value of the proposed Ranger Power facility and a new natural gas plant.

Figure 2 above shows the accredited capacity a new gas plant could expect to receive under the DLOL accreditation metric. Table 4 below displays the number of solar acres needed to match the capacity value of the hypothetical combined cycle natural gas plant in each illustrative planning year and compares this total to the land area of Cerro Gordo County.

Matching the accredited capacity of one natural gas plant with solar in 2030 would require over 105,792 acres of solar panels, roughly 29% of the total land area of Cerro Gordo County.

Now, Let’s Do All of Iowa

According to MISO’s Planning Resource Auction results for the 2025/26 Planning Year, Load Zone 3 covers basically Iowa, slivers of Southern Minnesota, and a tiny part of Northern Illinois.

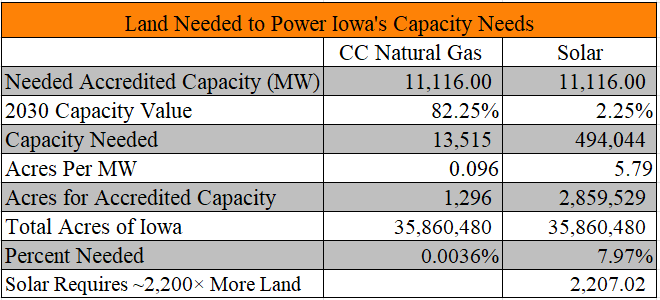

According to the MISO documents, this region has a peak summer planning reserve margin requirement of 11,116 MW.

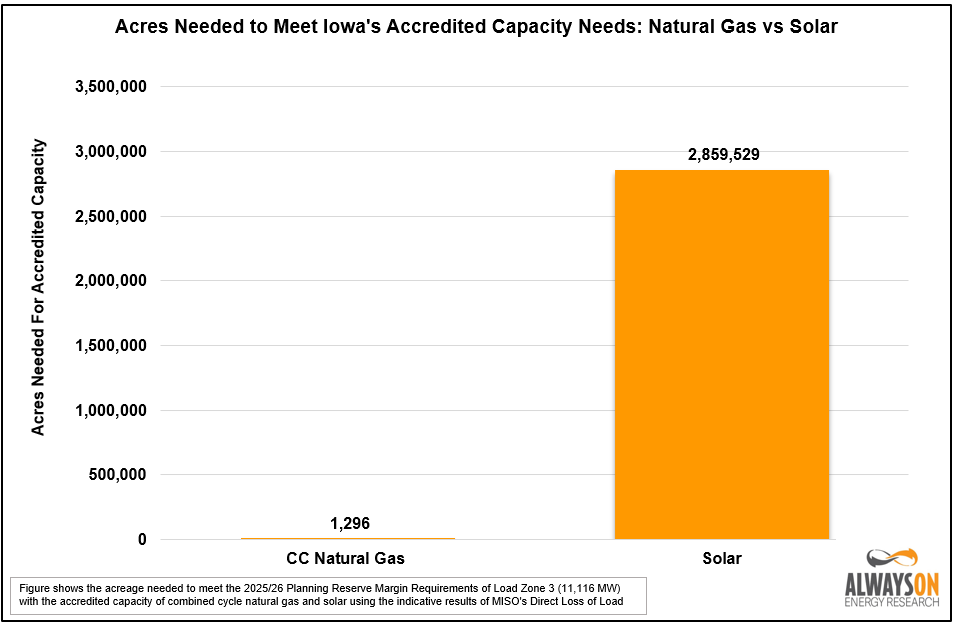

If we were to meet this with natural gas, it would require 1,296 acres of land, which is 0.0036 percent of all the land in Iowa. In contrast, meeting this capacity obligation with solar would require 2.86 million acres, or roughly 8 percent of the state’s total landmass.

For the math majors at home, this means it would take 2,207 times more land to meet Iowa’s capacity needs with solar than with natural gas. Just for fun, let’s look at how this looks in a bar chart.

The most obvious retort to the information in this graph is “no one is going to depend on solar to provide all of the capacity needed to meet your peak demand and reserve margin.”

However, as we saw in Witness Brown’s testimony, solar advocates have been crowing about the capacity value of the resources without acknowledging that it is about to drive over a cliff under DLOL, rendering it essentially useless as a capacity resource.

Conclusion

Solar can provide energy to the power system, but it is becoming increasingly clear that its value as a capacity resource is diminishing quickly. This has obvious implications for reliability, but it will also impact utility planning and land use issues that are playing out at utility commissions across the country.

Fear not, your tireless Energy Bad Boys will continue applying this same capacity-based framework to other states and technologies in upcoming analyses. All we ask in return is for you to share, subscribe, and give us all of your money.

Be the first to comment