From Garfield Reynolds, Bloomberg Markets Live reporter and analyst

The fate of pension funds at the heart of the recent gilts meltdown is a chilling warning for any bond investors trying to rely on historical data during these unprecedented times.

Global markets were already bruised and volatile even before the sudden massive policy misalignment between the UK’s government and central bank set off wild moves in the third-largest developed bond market.

But the key lesson for investors lies in those pension funds and how they came to matter so much. First of all, there are almost certainly other land mines hidden across the investment landscape, created by the extremes in monetary and fiscal policy of the past few years. It can hardly be a coincidence that pension funds looked to derivatives to provide long-term returns after a range of drivers, most notably a Covid-induced wave of quantitative easing, sent 30-year gilt yields to extreme lows on a nominal and especially an inflation-adjusted basis.

Meanwhile, investors keep getting drawn in by the juiciest yields they’ve seen since before the global financial crisis. That sort of appetite is an enormous risk if inflation stays high — especially given policy makers’ fear of avoiding a repeat of the 1980s, which will make them slower to cut interest rates than in the past.

Elevated inflation is in many ways merely a symptom of the deeper challenges facing the global economy, but it’s so potent it threatens to obscure a number of unprecedented shifts taking place.

First, deglobalization. The tariff wars and then the pandemic disrupted the once-core assumption that growing world trade would go on driving up growth and pushing down costs.

Then, the China-US relationship turning into a zero sum game. The two largest economies are competing to be king of the heap rather than enjoying a complementary relationship.

The major war on Europe’s doorstep is unleashing a level of global uncertainty rarely seen, complicated by the transition to a multipolar world from the bipolar one of the Cold War.

Climate change, starting with the direct impacts of the barrage of extreme weather events. But also the acceleration of a transition from fossil fuels, driven by those “natural disasters” and the man-made catastrophe of Russia’s invasion.

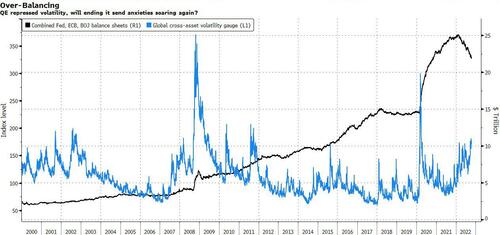

Then there are the central banks themselves. Never in the history of modern markets have global policy makers bought such a large proportion of their own bond markets, repressing yields and distorting trading conditions. Now the plan is to unwind all of this and, of course, central bankers have been carefully modeling their way toward that transition based on historical data that mostly covers the era before the massive growth in QE took place.

Here’s hoping any such modeling doesn’t run into the sort of reality check that hit UK pensions.