Decarbonising the world’s energy while securing the uninterrupted availability of power sources at affordable prices is the underlying challenge at this year’s climate summit, amid ongoing catastrophic climate events and the global energy crisis.

Russia, the world’s largest fossil fuel exporter in 2021, left the world exposed to extreme energy price volatility after it launched its invasion of Ukraine in February, showcasing the global economy’s dangerous reliance on fossil fuels and slow transition to renewables.

“Energy security and decarbonisation are not mutually exclusive – actually decarbonisation is the root to better energy security,” Richard Folland, senior adviser at Carbon Tracker, told Al Jazeera.

According to Folland, “renewable-based systems can provide better energy independence by being domestically generated energy sources and reduce dependence on oil and gas from regimes such as Putin’s Russia”.

In its annual World Energy Outlook, the International Energy Agency (IEA) found the Ukraine conflict was acting as a catalyst for clean energy transition, despite some countries resorting to band-aid solutions to make up for dwindling Russian natural gas exports.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has warned the world is on a “highway to climate hell” and repeatedly hailed renewables as “the only credible path” to real energy security.

COP27 delegates, however, are advocating for diversifying power generation, including nuclear power and fossil fuels in the energy mix.

What is energy security?

Since the invasion of Ukraine sent the world scrambling to replace Russian gas supplies, “energy security” has become a well-worn phrase.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen last month said Europe was “at a critical juncture for the security and stability of the European continent”.

“We therefore also need to rethink and reshape energy security in Europe,” she said.

According to the IEA, long-term energy security is mainly making timely investments to supply energy in line with economic developments and environmental needs; in the short-term, it relates to the ability of the energy system to react promptly to sudden changes in the supply-demand balance.

The global energy crisis has in the short term caused a spike in the use of highly polluting coal to bring down fuel costs, the IEA said, but the spike is temporary as the globe transitions to cleaner energy sources.

The organisation forecasts the worldwide demand for every type of fossil fuel will peak by the mid-2020s and then decline steadily, while clean energy investments will increase from $1.3 trillion per annum in 2021 to more than $2 trillion a year by 2030.

A study by the independent think-tank E3G found that given the rampant inflation mainly caused by the high price of gas, renewable energy capacity saved the European Union 99 billion euros ($102bn) in avoided gas imports since March, a record increase of 11 billion euros ($11.3bn) compared with the same period last year.

“We would argue that if you compare the cost of wind and solar with gas, they are becoming cheaper and cheaper, so moving into that renewable space system is a win-win both in terms of costs but also in terms of emissions,” Folland said.

What path to net zero?

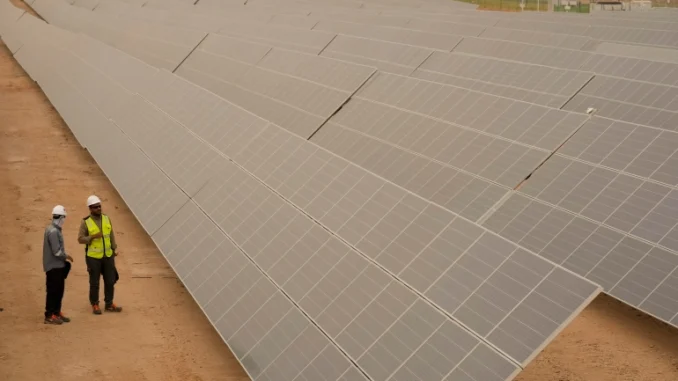

Wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles are core ingredients in sustainable energy mixes, but their rollout remains painstakingly slow.

While IEA projects investment to surpass $2 trillion per year by 2030, this amount is still half what is needed to meet net zero targets.

“Connecting renewables into our electricity grids and then [spreading] this as far across your economy as it can possibly go would do a lot of decarbonisation already,” Ben McWilliams, climate policy consultant at Bruegel, told Al Jazeera.

A dizzying array of bureaucratic hurdles and regulatory obstacles have created long delays, McWilliams said, but conceded the task ahead “is an infrastructure build-out of huge proportions” that has historically required decades rather than years.

As markets increasingly incorporate intermittent renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, some stakeholders at COP27 argued maintaining the supply-demand balance also called for the use of nuclear power plants and fossil fuel-based solutions.

Nuclear energy supporters on Wednesday took the stage in Sharm el-Sheikh to argue that atomic power offers a safe and cost-efficient way to decarbonise the planet.

“We don’t get to net zero by 2050 without nuclear power in the mix,” US Special Climate Envoy John Kerry told COP27.

The United States has earmarked billions of dollars for nuclear energy projects as part of a broader strategy to decarbonise its economy, investing in new projects including a new generation of small nuclear power plants that run on HALEU enriched uranium – which, as critics were quick to point out, is currently produced only by Russia.

Meanwhile, the EU announced last week it would sign three initial agreements for imports of so-called “green” hydrogen at COP27 with Kazakhstan, Egypt and Namibia.

As part of its strategy of diversifying natural gas supplies, it also revived the Baltic Pipe and listed the controversial EastMed pipeline as one of its Projects of Common Interest (PCIs).

While scientists say leaving coal, oil and gas in the ground is necessary to meet the Paris Agreement goals and keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), the EU has endorsed fossil gas as a “transition” fuel under its sustainable finance taxonomy earlier this year, while African stakeholders at COP27 are advocating for the need for fossil fuels to expand their economies and electricity access.

One of the lingering questions at COP27 has been whether African nations should receive financial support to produce, use and export natural gas as part of what African leaders say is a “just” energy transition that keeps economic needs into consideration.

But advocates for renewables have pitched themselves against governments, locking into fixed contracts and long-term infrastructure projects that could end up becoming stranded assets.

“It is not clear how much hydrogen we are going to need so it’s hard to make investments – you could be putting your company on the line,” McWilliams said. About half of the world’s fossil fuel assets will be worthless by 2036 under a net zero transition, according to research published by the journal Nature.

Some groups have pointed to the lack of political will as the main impediment to a full renewables rollout. More than 600 delegates affiliated with the fossil fuel industry are attending this year’s climate talks, campaigners have found, a number greater than the combined delegations from the 10 most climate-affected countries.

‘Holding us back’

Pascoe Sabido, researcher at the Corporate Europe Observatory, told Al Jazeera that locking countries into long-term investments would ultimately result in greater instability for the average household.

A report published by the organisation earlier this month found that while Shell, TotalEnergies, Eni and Repsol made a staggering 78 billion euros ($80.8bn) so far this year, more than 100 lobby meetings with high-level EU Commission officials delayed measures aimed at mitigating the cost-of-living crisis.

EU and US oil and gas lobby groups also worked with senior members of the European Parliament to push for more domestic gas production and more imports, the report found.

“What’s happening is that gas industry is locking us into energy insecurity,” Sabido said.

“The gas industry is holding us back from moving away from the fossil fuel industry and towards technologies that would allow us to have power in our own house – but that would undermine their power and their profits.”