ENB Publishers Note: The hypocrisy of California is sad. “Let’s save the planet” but turn a blind eye to being one of the largest reasons the Amazon rain forest is being destroyed through importing oil through California. “Among the top 25 largest corporate consumers are companies such as Costco, PepsiCo and Amazon, according to the report.”

YASUNÍ NATIONAL PARK, Ecuador — The bulldozers rumble through after sunrise, clearing out massive amounts of trees in this remote and remarkable section of the Amazon rainforest.

It’s a place where giant otters patrol the waterways and endangered white-bellied spider monkeys swing from tree to tree. Where a dazzling array of birds — upward of 600 species — nest in the dense canopy. Where more than 60 kinds of snakes and 140 different frogs and toads inhabit the ground below.

The Yasuní National Park is home to one of the most diverse collections of plants and animals on the planet. But beneath this 3,800-square-mile swath of forest lies another kind of treasure: crude oil. More than 1 billion barrels of it.

Over the past 50 years, oil companies have extracted immense amounts of crude from the Amazon, causing the destruction of rainforest crucial to slowing climate change and jeopardizing the Indigenous tribes who rely on it.

Now, a state-run oil company that subcontracts its field operations to the Chinese is building a road to reach what will be a new section of wells deep inside Yasuní.

“It hurts me to see the little that is left of our rainforest inside this protected area,” Nemo Guiquita, a leader of the Waorani tribe, told NBC News during a boat trip through the national park. “We should be fighting to protect our rainforest in Ecuador, but instead they are granting more oil concessions.”

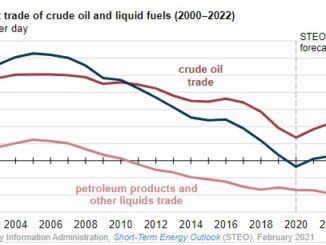

The oil extracted from Yasuní and the wider Amazon is exported around the world, but 66 percent goes to the U.S. on average and the vast majority of that to one state in particular: California, according to a new report shared exclusively with NBC News.

The report by the environmental groups Stand.earth and Amazon Watch found that on average 1 in every 7 tanks of gas, diesel or jet fuel pumped in southern California last year came from the Amazon rainforest. Among the top 25 largest corporate consumers are companies such as Costco, PepsiCo and Amazon, according to the report.

“This is no longer one of those things where we’re supposed to have sympathy for a crisis that’s happening somewhere else,” said Angeline Robertson, a senior researcher at Stand.earth and the lead author of the report. “It’s occurring in California, and it’s linked to Amazon destruction.”

Oil boom and bust

Oil drilling in the Ecuadorian Amazon began in the 1960s with the promise of bringing prosperity to the coastal South American nation. A symbolic first barrel of crude oil was paraded through the streets of the capital city, Quito, as if it were a national hero.

Ecuador’s economy soared over the next decade. But by the 1990s, the oil boom had faded, and the country entered a severe recession, resulting in a flurry of deals with foreign oil companies and eventually mounting debt.

Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso, who was sworn in this past May, has vowed to double the country’s oil production. Perhaps nowhere is expected to be impacted more than Yasuní National Park.

The park in eastern Ecuador — which sits at the confluence of the Andes foothills, the western Amazon basin and the equator — is about the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

It contains more varieties of trees in a single hectare (2.5 acres) than in all of the U.S. and Canada combined. Yasuní is also the home of the Waorani people as well as two uncontacted tribes who live deep inside the forest: the Tagaeri and the Taromenane.

Oil exploration began here in the 1970s, but in 2007 then-President Rafael Correa proposed a novel plan to protect the rainforest from drilling. He called on the international community to donate about $3.5 billion — roughly half of the revenue Ecuador estimated it would have earned from mining the oil under Yasuní. But the plan was abandoned six years later, after Ecuador raised less than 10 percent of the target figure.

“The world has failed us,” Correa said in 2013 as he announced a lifting of the moratorium on oil drilling in Yasuní.

The move to drill hundreds of new wells in the national park requires the building of roads and other infrastructure that is likely to accelerate deforestation, environmentalists say. Construction of an initial road inside the park is now less than 1,300 feet from the “no-go” zone designed to protect the uncontacted tribes, according to the report.

Kevin Koenig, the climate and energy director for Amazon Watch, noted that forests like this one play a vital role in mitigating climate change. Forests absorb immense amounts of carbon, which helps to reduce the rate at which carbon dioxide builds up in the atmosphere.

“It’s a recipe for climate disaster to be looking for new oil and felling standing forest to get at it,” Koenig said. “It’s sort of a double whammy that everybody should be really worried about.”

Gas flares

Nemo Guiquita, the Waorani leader, has been fighting the expansion of oil drilling in her tribe’s ancestral homeland for years. She said her grandmother, Nayuma, was the first Waorani to make contact with the outside world 60 years ago.

“The rainforest for us is home,” Guiquita said. “It’s our life, our pharmacy, our everything.”

More than 400 gas flares dot the scarred landscape in the Ecuadorian Amazon. They spew clouds of chemicals into the air from the burning off of natural gas produced from oil wells.

In January, an Ecuadorian court ordered oil companies to cease the use of gas flares after a group of Amazonian girls filed a lawsuit alleging that the flares contaminated the air and water in the area and contributed to more than 200 cancer cases among their community.

Javier Solis, a lawyer who represents one of the local communities, said the government has yet to set a date for the removal of old flares. Solis escorted an NBC News videographer into a section of forest outside Yasuní to see what he described as one of the Amazon’s biggest oil flares.

“The contamination can reach a circumference of 300 meters [330 yards], and this affects the groundwater and rivers used by nearby communities,” Solis said.

For the rest of the story please go to NBC News.