Energy markets have been on a roller-coaster ride this year. In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western countries imposed financial sanctions on Russia and embargoed its oil exports. Russia cut its gas supplies to Europe in retaliation. Major importers such as Germany had to slash their energy use and look elsewhere for supplies. Low- and middle-income nations struggled to access affordable energy. Countries including Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka faced blackouts; fuel price hikes spilled over into food markets.

As the year draws to a close, much of Ukraine’s energy system lies in ruins. Global gas and electricity prices remain sky high and energy cartels and fossil-fuel-rich states are back in the driving seat. In 2023 and beyond, the energy crisis will have profound consequences for where the world is heading and how it can get on track to a greener future. But what exactly are the consequences, and how should policymakers respond? Here we set out five areas in which researchers can — and must — deliver answers.

How will the map of global energy change?

Events of the past year have fundamentally altered Russia’s position in global energy markets, and the shape of those markets. New alliances are being built and old ones consolidated. In 2021, Europe received more than half of Russia’s oil exports and around three-quarters of its gas sales. Now, the European Union is approaching major gas suppliers such as Norway, Algeria and the United States, as well as producers of liquefied natural gas in Africa and the Middle East (see Nature 604, 232–233; 2022). In 2023, in a historic shift, EU states will club together to purchase enough gas to refill 15% of their stores. The extent to which the EU will coordinate this move with its other partners in the G7 group of advanced economies will be important to watch. Success would increase the EU’s bargaining power and strengthen political solidarity among G7 partners, which, together with Australia, set a price cap earlier this month on Russian oil exports worldwide.

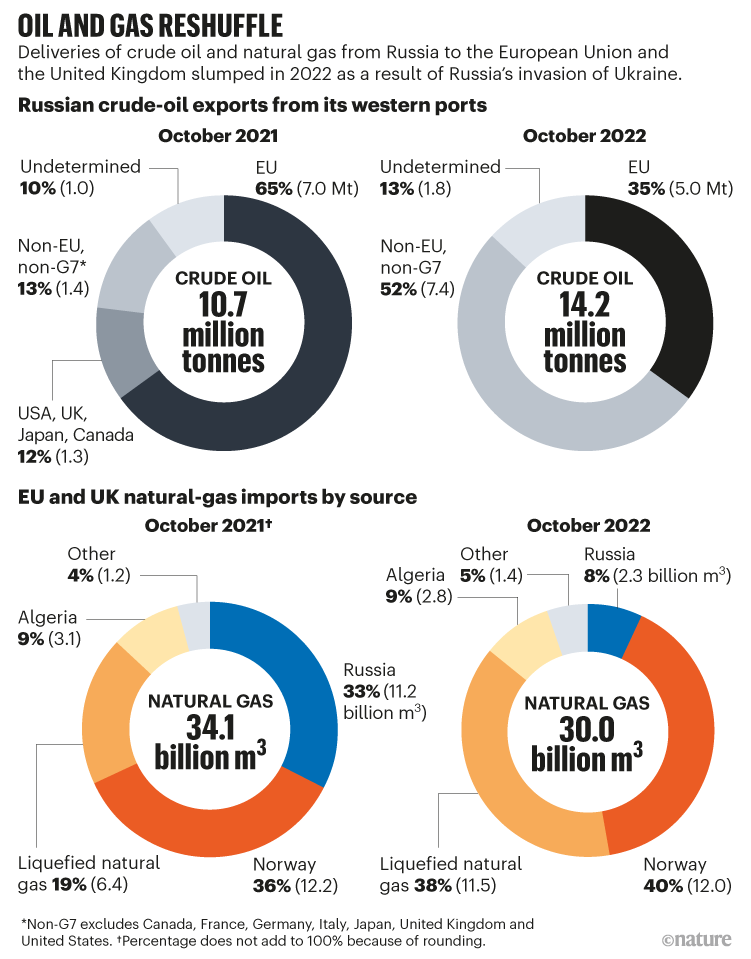

Meanwhile, Russia is shifting its lost European exports east to Asia, mainly China and India (see ‘Oil and gas reshuffle’). It might end up as a junior partner in these relationships, especially with China. Yet it could still retain or increase its influence in the OPEC+ fossil-fuel alliance, especially if Saudi Arabia continues to alienate the United States, its usual ally.

Source: Bruegel

Europe will see lasting reductions in its consumption of natural gas as a result of greater energy efficiency, a switch to green alternatives and the transfer, or offshoring, of energy-intensive industries, such as steel and fertilizers, to other nations. East Asian countries will want to reduce their dependency on expensive liquefied natural gas and turn to cheaper coal. The United States is developing its renewable and fossil-fuel domestic energy resources to insulate itself from global energy tensions and price volatility.

Globally, whether investments shift from gas infrastructure to coal or renewables will have deep consequences for carbon budgets. Some long-standing axioms must be abandoned, such as the role of cheap gas as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a green energy system.

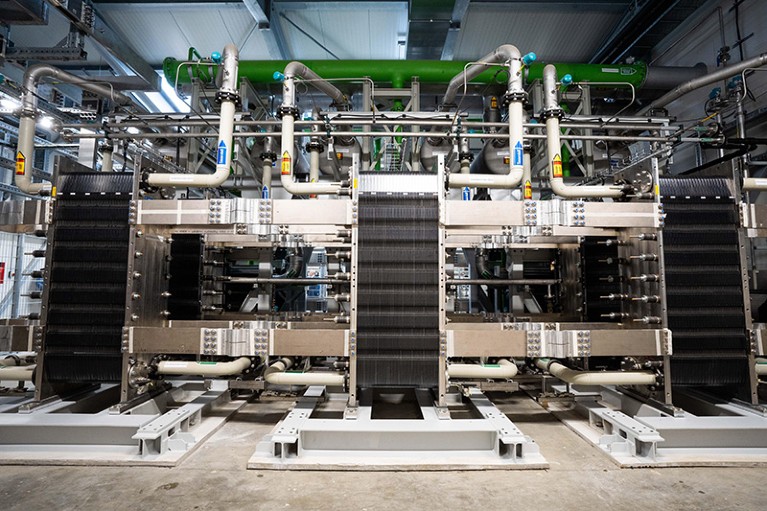

Other energy solutions are also getting a boost, notably green hydrogen — obtained from water using electrolysis powered by renewable energy. For instance, the Canada–Germany Hydrogen Alliance, announced in August, is aligning policies and investments to develop hydrogen supply chains between the two countries. The EU is refocusing its energy trade ties with African nations, including Algeria, Nigeria and Namibia, towards green hydrogen and ‘power-to-X’ technologies, which use clean electricity to make synthetic natural gas, liquid fuels or chemicals that are carbon neutral.

In 2023, researchers need to consider whether such steps are enough to compensate for lost Russian imports and avoid global supply shortages. They must assess strategies for juggling supply and demand for liquefied natural gas in a tight market, and as Chinese manufacturing ramps up after closures due to COVID-19. Energy economists and political scientists must model incentives, trade-offs and cost implications, to inform how regulatory and policy tools must be redesigned.

The technological and economic viability of new energy projects must be investigated. Some have been hastily proposed, rejigged or fast-tracked. For example, the BarMar pipeline, a joint project by France, Spain and Portugal, aims to pipe natural gas — and later green hydrogen — through an undersea network between Barcelona and Marseilles in the next 4–5 years. The technical and economic viability of such infrastructure remains to be established, however.

Russia’s ability to redirect oil and gas exports to Asia needs to be better understood. Russia can deliver oil by ship using the Suez Canal and the Arctic Ocean. Gas requires pipelines. A planned gas pipeline called Power of Siberia 2 aims to extend the connection between Russia and China through Mongolia after 2030, although sanctions on Russia could delay its construction. Researchers need to consider the degree to which infrastructural, administrative and economic bottlenecks might slow Russian exports to China and thus hinder its economy. Will sanctions work or will Russia develop home-grown solutions to dodge them?

Will sky-high energy prices boost renewables?

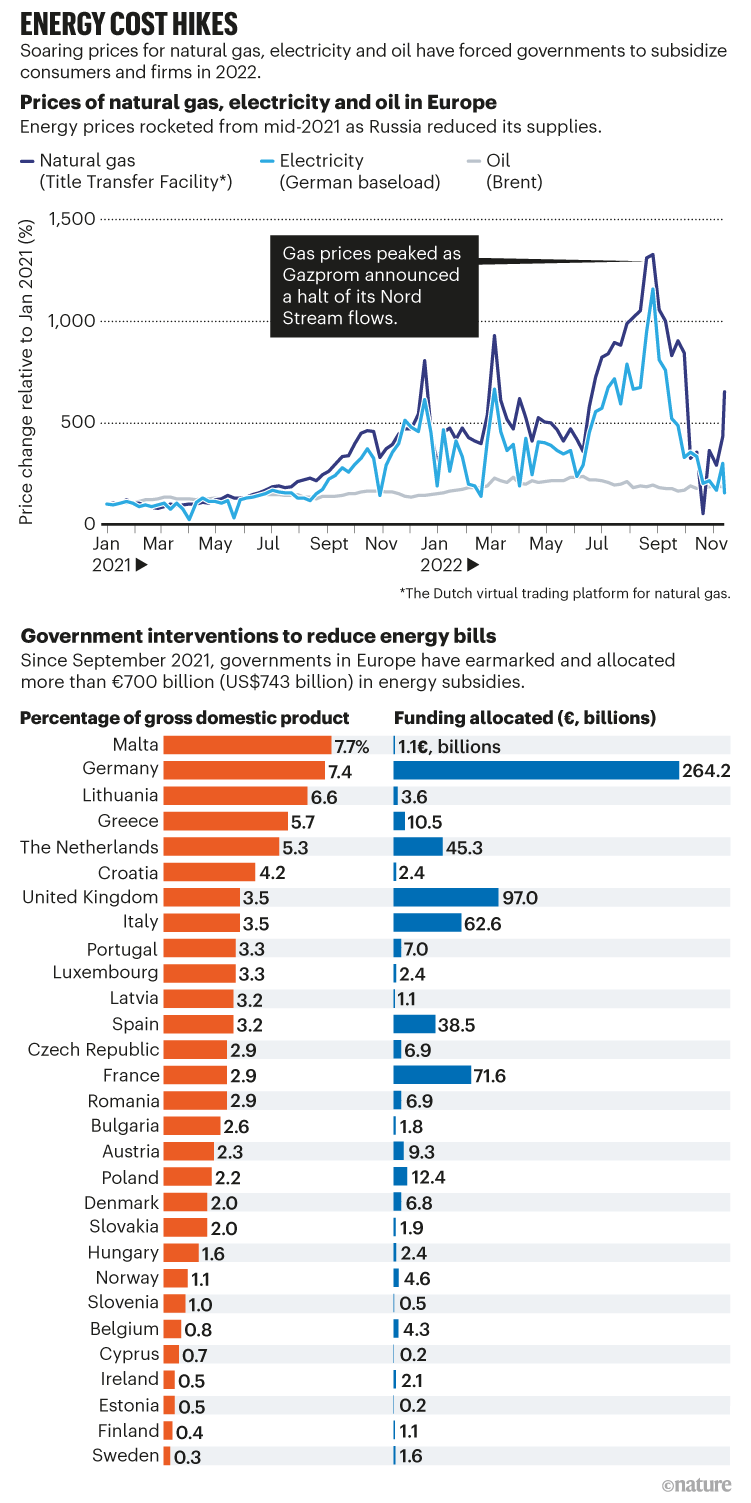

The extent to which countries can fast-track the switch to green energy is a key question for 2023. High global oil and gas prices (see ‘Energy cost hikes’; upper panel) offer an incentive for households and businesses to install solar panels and heat pumps to lower their energy bills, as many did this year in Europe. EU policymakers fast-tracked permits for installing renewables, and simplified regulations around retrofitting buildings to be more energy efficient. The United States this year passed its Inflation Reduction Act, which includes subsidies for manufacturing clean technologies domestically, which should boost uptake. Researchers need to see how these policy shifts pan out amid strengthening economic and political headwinds.

Source: Bruegel

Western countries are ramping up domestic manufacturing of green technologies to be less reliant on China, a geopolitical competitor. Russia’s war has amplified growing unease about China’s leading position in clean technologies and its control over key raw materials used in them, such as rare earth minerals. This year, the United States passed the CHIPS for America Act to strengthen its domestic semiconductor industry, which is central to all electronic products. The nation has also banned imports from China’s Xinjiang region — a manufacturing powerhouse for solar panels — in response to reports of forced labour there.

But the jury is out on the feasibility and value of such ‘reshoring’ — returning the production and manufacturing of goods back to a country. In areas such as solar power, China has for decades invested billions of dollars in becoming the dominant processing hub. Rather than replicating that, a smarter strategy for European countries and the United States might be to focus on developing the next generation of technologies, including sodium batteries or thin-film, non-silicon solar panels.

Countries with reserves of key metals and minerals such as cobalt and lithium also need attention. They might not necessarily experience a ‘gold rush’: as the Middle East has seen for oil, resource wealth can foster conflict. Exports in foreign currency can depress the domestic economy, as has happened in Nigeria and Venezuela. Researchers need to assess the economic and social impacts of such ‘green extractivism’ in low- and middle-income nations.

The widening gap between low-carbon leaders and laggards should be monitored. Investment imbalances are dire: in 2021, developing and emerging economies received a mere 8% of all clean-energy investment — most of the rest went to industrialized countries and China1,2. There are implications for economic development3: if investors steer clear of countries with coal-based energy systems, many low- and middle-income nations will find it harder to catch up and industrialize. More money needs to be made available to them. So far, national pledges to the Green Climate Fund have come up short. What’s needed are more initiatives such as the Global Climate Alliance4, proposed at the COP27 climate conference in Egypt last month. These commit rich countries to contributing to a climate financing pool using funds generated through carbon tax programmes and other methods. The pool is then distributed between low- and middle-income countries, depending on their climate commitments.

Ultimately, the nature of the decarbonization transition is a political choice. Does the world tackle the transition as a global commons challenge — requiring joint efforts from development banks, financial institutions and clubs of governments from the G7 to the G20? Or as a green race — accepting winners and losers and the consequences, including poorer prospects for countries that fail to attract ‘clean’ capital? Researchers need to supply evidence to help decision makers.

How will the industrial landscape shift?

High costs and limited supplies of energy will reorganize industries, including processes and locations. This will take time, but decarbonization is being brought forward by years as structural changes are put in place — and the effects are already being felt.

Some energy-intensive manufacturing sectors, including for aluminium, fertilizers and other chemicals, are starting to move to places offering cheaper energy, such as the United States or the Middle East. Other industries are innovating. European steel makers are investing in converting to green hydrogen and teaming up with energy companies to build large wind-to-hydrogen facilities. Car makers are turning to chassis made of ‘green steel’ forged using renewable energy, and to wheels made of ‘green aluminium’ produced using low-carbon methods.

Workers manufacture photovoltaic modules for solar panels in Jiangsu province, China.Credit: CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty

In the longer term, facilities for steel, aluminium and power-to-X technologies will increasingly be sited in areas rich in sunlight, wind, hydropower and biofuels. Regions such as North Africa, Western Australia, the North Sea fringe or parts of the Middle East could emerge as economic powerhouses. Established manufacturers at the end of a gas pipeline or near a coal mine will lose their competitive edge. Deindustrialization — a much-feared threat to advanced nations, given its repercussions for employment and economic growth — is a real risk, and might heighten social tensions and political backlash against decarbonization.

Researchers need to inform new business models to help heavy industry to adjust swiftly while remaining competitive. These models will need to be rapidly refreshed as conditions and practices change. For example, petrochemical refineries will survive in the long run only if they switch to low-carbon liquid fuels and can commercialize them. How can costs come down, and what sort of public support might help to bring viable clean products to market quickly?

Little is known about future supply chains for green technologies. Production and transportation costs for green hydrogen need to be worked out. Ammonia is a promising way to transport such fuel over long distances, but the commercial prospects of this remain in question.

Ultimately, the pace and shape of the green industrial transition will depend on how countries organize production, labour and state interventions (such as subsidies) in their economies. Liberal-market countries, such as the United States or United Kingdom, might radically innovate their way out of the fossil-fuel age. But how will they manage legacy industries, such as coal, steel or chemicals? Corporatist economies, such as Germany or France, are good at implementing incremental industrial change through collaborations between public authorities and organized labour5. Will they thrive, or will their economies be slowed by keeping alive old sectors that might then become liabilities? Researchers should help governments to decide which sectors deserve subsidies, which face a bleak future and how energy transformations can be incentivized.

What will the lasting economic impacts be?

The coming year will bring clarity about trends in ‘deglobalization’ and economic nationalism. Some economists predict that reshoring will slow the global energy transition as markets fragment. Researchers also need to watch what happens to the global division of labour that drove the development of clean technologies and slashed the cost of solar panels in the first place — a blend of innovation in the United States, Chinese investments in manufacturing and subsidies in Europe. If countries act in isolation and do so purely competitively, this virtuous circle might break.

This year, governments made huge financial interventions in energy markets, well beyond crisis management. Since last September, European governments have earmarked more than €700 billion (US$743 billion) in energy subsidies to ease the pain for families and businesses facing record prices (see ‘Energy cost hikes’, lower panel). Energy companies also received support; some were nationalized, including in Germany and France. The EU Energy Platform, which will pool purchases of natural gas (and later hydrogen), amounts to a cartel in the making. Researchers need to ask whether these events are temporary exceptions or lasting reorientations. What’s at stake is the idea of open global markets driving the effective allocation of scarce resources, rather than top-down state planning.

A hydrogen generation plant in Wunsiedel, Germany.Credit: Nicolas Armer/dpa/Alamy

The energy crisis is exacerbating social inequality within and between countries. Vulnerable households and low- and middle-income nations have been hit hardest by energy cost hikes. The repercussions are deep. The energy crisis might yet spill over into a fiscal or debt crisis — the debt burden of developing countries has reached a 50-year high in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (see go.nature.com/3hnrcky). Vulnerable economies could see their industries contract. Spiralling state support for ailing sectors empties public pockets and dwindles foreign exchange reserves, with the risk of increasing risk ratings for financial borrowing.

Researchers must evaluate the implications for national policies and multilateral aid, lending and development policies. They should shed light on the extent to which increasing energy poverty, energy price shocks and energy-induced inflation weaken social cohesion and threaten political stability. Rich nations can also be affected, as protests in the United Kingdom and Czech Republic attest.

How will the energy crisis affect climate action?

The ramifications here are potentially severe. Low- and middle-income nations are uneasy with Western responses to the energy crisis; rich countries that are turning to coal to replace Russian imports while calling on poorer nations to do their utmost to decarbonize seem hypocritical.

As budgets take a hit, rich countries will fall further behind on their climate finance targets (see Nature 598, 400–402; 2021). Climate initiatives that divide nations into trading blocs — such as climate clubs that manage tariffs on embedded carbon in imported goods, as proposed by the G7 — might create tensions between rich and poor nations if they are not properly aligned with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in global climate action6.

Social and political scientists and economists need to identify which bilateral, regional and multilateral mechanisms are best placed to foster climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building as pledged under the Paris climate agreement. A re-examination is needed of cross-border carbon measures6.

Following support at the COP27 climate meeting, research will also be needed into the design of a global ‘loss and damage fund’ to compensate countries for the direct impacts of climate change. What form such a fund should take, what types of activity it should support and how it can be funded by rich nations and under what conditions, all need to be decided. Otherwise, tensions between nations will grow and risk stalling climate talks — losing time we do not have.

The energy crisis is an opportunity as well as a challenge. As the clock ticks over into 2023, researchers must deliver answers to protect the green-energy transition.

Source: Nature.com