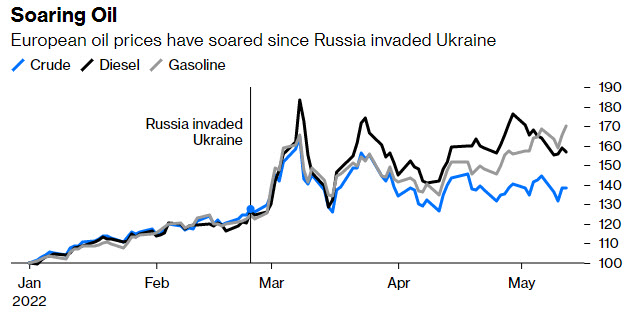

Sunday is the day when European Union regulations prohibiting dealings with Russian state energy companies come into effect. That should trigger a further decline in the volume of crude and refined products bought and traded by European companies, but it won’t bring flows to a halt.

Even when, or if, the EU finally imposes sanctions on the purchase of the country’s oil, it won’t stop “Russian” crude leaving Russian ports, nor the products made from it from fueling European cars and trucks.

There are several reasons why.

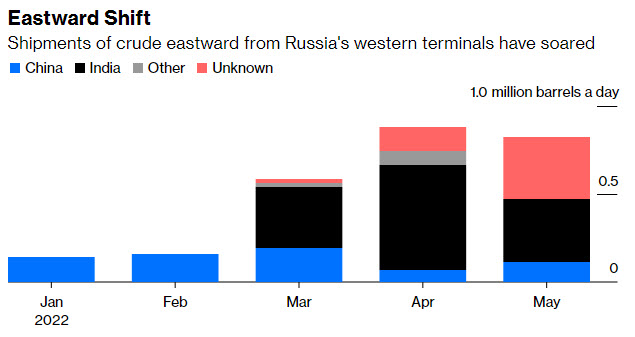

Russia will do what it can to keep shipments moving. Crude will continue to flow to China and India, and in growing volumes. Seaborne shipments will depend increasingly on Russian ships. State-owned Sovcomflot PJSC operates a fleet of more than 100 oil tankers, ranging from so-called Medium Range vessels, able to carry 40,000 tons of refined products to regional markets, all the way up to the largest crude carriers that can haul eight times as much over huge distances.

Destinations based on signals from tankers at the time of compilation. These may change. May figures are for the first 13 days.

The vessels used on Russia’s overseas trade have largely been shunned since the UK added Sovcomflot to its list of sanctioned entities, prompting international insurers to distance themselves from the shipowner. The company’s largest ship, the 340,000 deadweight ton supertanker Svet, hasn’t carried a cargo since delivering a consignment of Angolan crude to China in February.

Insurance for Sovcomflot ships plying the route to India will probably be provided by the Russian state, rather than the mutual insurance associations, or P&I clubs, that typically perform that role.

But the trade from western Russia to Asian markets has soared since the invasion of Ukraine and looks set to increase further. Cargoes have also started to be discharged at Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates, where the crude can either be refined, or stored, blended and resold.

There will also be exemptions for crude that transits Russia, mostly from Kazakhstan, but also in much smaller quantities from Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. I dealt with the case of CPC Blend crude from Kazakhstan here, but traders will be still be able to lift what looks to outsiders like Russian Urals or Siberian Light crude. This isn’t an attempt to evade sanctions.

While most of the molecules in those cargoes will have been pumped from the ground in Russia, the legal provenance will be elsewhere. Kazakhstan, for example, pumps crude into the Russian pipeline system. That crude is blended with volumes from Russian oil fields to make the standardized exports grades — REBCO (Urals) and Siberian Light. Kazakhstan is then allocated the same amount of crude as it put in the system to be loaded onto tankers at Russian ports.

Even though the financial transaction is between the buyer and Kazakhstan, the cargo looks Russian. It is branded as a Russian grade and loaded at a Russian port. That may cause all sorts of reputational risks for companies, like Vitol Group, that handle Kazakhstan’s Urals exports.

While Europe may stop buying Russian crude, it’s unlikely to be able to avoid diesel fuel made from that crude. The direct diesel trade between Russia and European countries may halt, but product made from Russian crude in overseas refineries will still arrive at European ports. Russian crude processed in overseas refineries ceases to be Russian. Diesel produced at, say, an Indian refinery is Indian diesel, no matter whether the crude came from Saudi Arabia, Russia, or anywhere else. Products are made to tight specifications required in consuming countries and there is no mechanism to determine where the crude they were produced from originated.

The purpose of the EU measures already imposed and the proposed sanctions it is trying to get adopted by member nations is not to stop oil coming out of Russia, per se. It is to stop, or at least greatly reduce, the revenue Russia earns from exporting oil. At the same time, the world continues to need at least some of that oil to keep flowing if we are to avoid another surge in prices.