Recent developments

Bloomberg reported on 19 February that the U.S. might hold off on sanctioning German companies involved in the Nord Stream 2 project, as the Biden administration seeks to halt the project without antagonizing a close European ally. It would instead put only a small number of Russia-linked entities on the list.

German, U.S. and international media such as Handelsblatt, Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times reported in mid-February that the administration of new President Joe Biden might be willing to make a deal with Germany on Nord Stream 2, according to government sources. It remained unclear whether Biden would even consider to do so in the face of clear bipartisan opposition in the U.S. Congress. A deal could involve waiving sanctions in turn for an agreement that Germany would shut off future natural gas deliveries through the pipeline, for example in case Russia put pressure on Ukraine.

After more than a year of threatening to do so, the U.S. had introduced first sanctions on 19 January, former president Donald Trump’s final full day in office. The administration sanctioned the Russian ship Fortuna, which later resumed pipe-laying in Danish waters on 6 February.

The pipeline was originally scheduled for completion by the end of 2019. About 2,300 km out of approximately 2,460 km had been laid by December 2019, when Swiss pipelaying company Allseas suspended activity following the introduction of U.S. sanctions legislation. By mid-February 2021, about 150 km – 75 km per strand of the twin pipeline – still had to be completed, mostly in Danish and to some extent in German waters.

In late January 2021, the European parliament called for a halt to Nord Stream 2 after the arrest of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. On the same day, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reaffirmed her support for Nord Stream 2. “My basic attitude has not yet changed to the point where I say the project should not exist,” Merkel said.

Calls to stop or at least put on hold the pipeline project had already gained traction among German politicians following the poisoning of Navalny at the end of August 2020. Norbert Röttgen, a lawmaker with Merkel’s conservative CDU, said that the completion of Nord Stream 2 “would be the ultimate confirmation for Vladimir Putin that he is pursuing exactly the right policy because the West is doing nothing, at least in the areas that interest him”.

In the first days of 2021, the regional government of the German state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, where the NS2 pipeline would land, had moved to set up a “climate” foundation to circumvent the threat of U.S. sanctions – an attempt that could turn out to be futile. The approach was widely criticised in Germany, also because the pipeline was presented as necessary for climate action. This prompted a new wave of oppositional voices in Germany, neighbouring countries such as Poland, and beyond.

The project

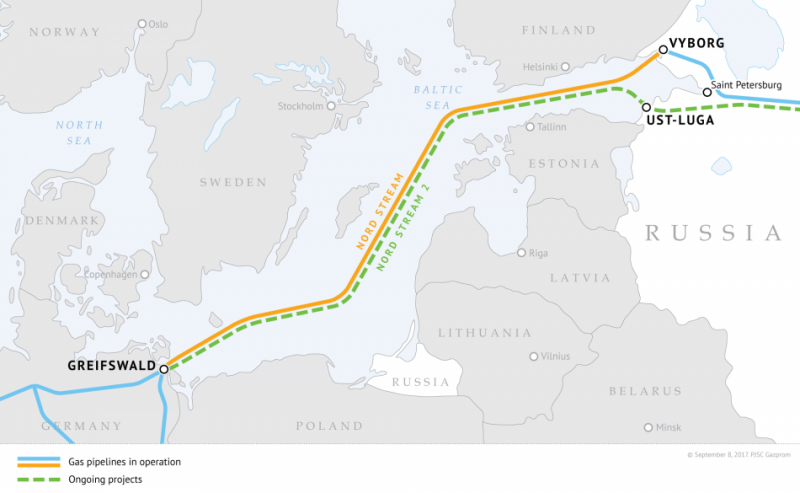

Nord Stream 2 is an underwater twin pipeline that would transport natural gas from Russia directly to Germany. At a length of 1,230 kilometres, it is to follow the route of the existing Nord Stream twin pipeline underneath the Baltic Sea. The original Nord Stream pipeline, with an annual capacity of 55 billion cubic metres (bcm), was finished in late 2012. The pipeline system’s total capacity is set to double to 110 bcm following Nord Stream 2’s completion. The pipeline crosses into the exclusive economic zones of five countries: Russia, Germany, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden.

Nord Stream 2 is being built by Nord Stream 2 AG, a consortium incorporated in Switzerland. Its chairman of the board of directors is Gerhard Schröder, German chancellor from 1998 to 2005 and the subject of fierce criticism for his ties to Russia.

Moscow-based, state-owned Gazprom is the project’s sole shareholder and has committed to providing up to 50 percent of the project’s financing, with the remaining funds coming from German companies Wintershall and Uniper, Royal Dutch Shell, French ENGIE, and Austrian oil and gas company OMV. According to Nord Stream 2 AG, the overall costs of the project will total around 9.5 billion euros.

The gas that the pipeline is to carry lies in northern Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, which holds nearly 5 trillion cubic metres of gas reserves, according to the Nord Stream 2 consortium. Once extracted, the gas is to be transported to coastal Russia. There, it is to pass through a compressor station – a facility that raises the pressure of the fuel – and then be fed into the pipeline. After entering into the Gulf of Finland, the pipeline is to re-emerge on land in north-eastern Germany, near Greifswald.

Russia, Germany, Finland, Denmark and Sweden have granted all the permits necessary for construction of the planned pipeline within their jurisdictions. Construction of Nord Stream 2 in Germany began in 2016 with the production of the steel pipes and continued with the digging of a trench on the seabed in May 2018. In July 2018, the first steel pipes were installed at Germany’s landfall in Lubmin.

The project’s supporters, which include the Russian government, the companies involved, and some German politicians, argue that the pipeline would both increase security of supply by connecting western Europe to the world’s biggest gas reserves and support sustainability goals by replacing coal as a less CO2-intensive complement to renewable energies. Germany is planning on phasing out its coal use in order to meets its CO2 emissions reduction targets, which will further strain its electricity grid, Nord Stream 2’s supporters contend. Proponents of the project also argue that Nord Stream 2 could provide the energy currently supplied by nuclear power plants, which are planned to be taken offline by 2022.

The United States, environmental groups, many German politicians, and several Eastern European countries oppose the project. Opponents argue that the pipeline would harm fragile marine ecosystems, jeopardise the bloc’s move to a low-carbon economy, increase European reliance on Russia for energy to a dangerous level, and empower Russia at a time that it is facing criticism for destabilising activities around the globe.

Supply

Proponents of the project maintain that, despite geopolitical concerns, Germany needs to import more gas and that the new pipeline could bring reliable and affordable supplies to the country. As the world’s biggest natural gas importer, Germany currently sources nearly all (94% in 2018 ) of the natural gas it consumes from abroad, according to the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Resources (BGR). Domestic natural gas production has been falling since 2004 and will likely cease altogether in the next decade, and further exploitation of Germany’s natural gas supplies via hydraulic fracturing remains unlikely.

Due to data privacy regulations, the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA) stopped publishing import volumes by country in 2016. However, it can be assumed that Russia, Norway, and the Netherlands continue to be Germany’s main suppliers, according to the BGR. In July 2018, a spokesperson for the German economy ministry put Russia’s share in German natural gas imports at “about 40 percent.” This was also the share for EU gas imports as a whole in 2018.

In 2015, 35 percent of German gas imports came from Russia, 34 percent from Norway, and 29 percent from the Netherlands, with the latter’s share due to drop because production in the Netherlands is being scaled back and potentially phased out by 2030. Proponents of the pipeline say that decreasing gas production within the European Union means that more of the fossil fuel will need to be imported in the coming years, much of it from Russia. This would increase Germany’s importance as a transit country to supplying the rest of the continent. German gas consumption has been on the rise since 2014, supplied largely by record imports from Gazprom. [For more on Germany’s dependence on foreign suppliers for natural gas, read our factsheet.]

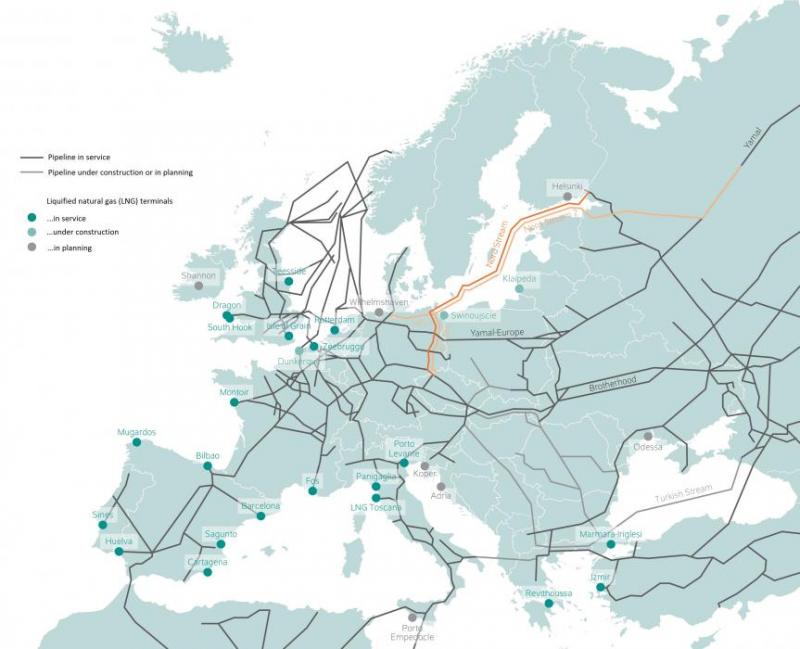

However, environmental think tank E3G has found that, even in a scenario in which the German power sector were to rapidly switch from coal- to gas-generated electricity, Nord Stream 2 would be unnecessary. As the report notes, “from a security of supply point of view, there is no need for new import capacity into Germany, like Nord Stream 2.” Instead, the think tank writes, imports via existing liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and pipelines would suffice to meet expected future needs.

Gazprom also constructs TurkStream, a 31.5 bcm twin pipeline at the bottom of the Black Sea, to supply both Turkey and south-east Europe with Russian natural gas. Commercial supplies via the first line commenced in early 2020, the second line is under construction.

Further complicating the debate, there is uncertainty regarding how German gas demand will change in the future. Whereas the BGR writes in a 2017 study that domestic natural gas use will grow, FNB Gas, the association of Germany’s gas transmission system operators, looks at two scenarios: one in which demand will grow and one where it falls over the next decade. The Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur) bases its plans for the development of the natural gas transmission network on FNB Gas’s scenario frameworks. [For more on the role of natural gas in the German energy system, read our dossier.] The German government makes few statements on expected total future gas demand, but emphasises that the fuel will play a more important role and that imports will also grow in importance as European domestic production declines.

Projections for future EU gas demand also vary widely, with some calling into question the need for additional import capacities. In a 2018 paper, the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) wrote that the energy consumption forecasts on which Nord Stream 2 is based “significantly overestimate natural gas demand in Germany and Europe” and that there will be no supply gap if the pipeline is not built.

In a 2017 study, energy research and consultancy organisation ewi Energy Research & Scenarios wrote that Nord Stream 2 would also help bring down gas prices in the EU. “When Nord Stream 2 is available, Russia can supply more gas to the EU, decreasing the need to import more expensive LNG. Hence, the import price for the remaining LNG volumes decreases, thereby reducing the overall EU-28 price level,” wrote ewi.

Environment

Nord Stream 2’s proponents and opponents also disagree over the pipeline’s environmental benefits and drawbacks. Supporters say that the pipeline could help Germany meet its carbon emissions reduction goals. [For more on Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions and climate targets, read our factsheet.]

Nord Stream 2 AG argues that replacing coal with natural gas benefits the climate because, when burned, natural gas emits less carbon dioxide than coal. However, depending on the volume of methane that leaks during the gas’s extraction, processing and transportation, precisely how much more beneficial for the climate natural gas is remains unclear. [For more read the article Unravelling the climate footprint of U.S. liquefied natural gas]

Even if natural gas were friendlier to the climate than coal, some climate change activists nevertheless believe that the project should be abandoned. In their view, the combustion of natural gas contributes to global warming, and the construction of a multibillion-euro pipeline represents an investment that will “lock” Germany – and the EU – into fossil fuels “for decades.” “If EU member states are serious about their commitments to tackle climate change, they should use every tool in the box to stop Nord Stream 2,” Marcin Stoczkiewicz wrote in Climate Home News in April 2017. Marine conservation groups also oppose the energy project, arguing that laying new pipelines under the Baltic Sea would lead to detrimental effects on ecosystems. The Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) had tried unsuccessfully to halt construction before local courts and the Federal Constitutional Court.

Geopolitics and security

The United States has long been an opponent of the pipeline and already-fraught transatlantic relations have continued to deteriorate over the project. The administrations of both Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump have clearly expressed their opposition to the pipeline, and the country introduced sanctions in December 2019, forcing pipelaying vessels by Swiss company Allseas to stop working on the project and leading to a months-long delay. Threats of more sanctions in mid-2020 now endanger the completion of the pipeline.

As do others, the American government contends that completion of the project would increase European reliance on Russia and imperil the continent’s security policy at a time when Russia is facing intense criticism for its alleged interference in Western democracies, aggression in Eastern Europe, and support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Secretary of State Pompeo called Nord Stream 2 one of “Russia’s malign influence projects”. In addition, the US has become a major exporter of LNG it aims to also sell to European customers. [Also read the article Coronavirus crisis highlights risks of U.S.-European LNG deals diplomacy]

Nord Stream 2 board chairman and former German chancellor “Gerhard Schröder supports Russian energy exports that in turn finance Russian war exports,” Reinhard Bütikofer, German member of the European Parliament and Green politician has said, while Norbert Röttgen, German conservative politician and chairman of the foreign affairs committee, has commented: “In my view, the federal government’s language regime that, as a private economic project, Nord Stream 2 has nothing to do with politics is unacceptable and provocative.”

For years, the German federal government had said that Nord Stream 2 is a purely economic project and that the state should not interfere. In April 2018, however, Chancellor Angela Merkel acknowledged concerns by the Ukrainian government and said the pipeline “is not just an economic project, but that, of course, political factors must also be taken into account.” Still, the government has remained in favour of the project.

Opponents’ geopolitical argument rests on the premise that because Gazprom is a state-owned enterprise, purchasing gas from the company funnels money directly to the government that is then used to commit nefarious activities both domestically and around the world. Money from gas and oil exports allow “today’s leaders in Moscow [to] do what they like doing most: enrich themselves; halt reforms; and grow the military, the FSB (Russia’s Federal Security Service) and the police apparatus,” journalist Gerhard Gnauck wrote in an opinion piece for Welt Online.

Finally, many countries in Eastern Europe, such as Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine, oppose Nord Stream 2, partially because of expectations of a loss of transit fees and partially because of fears that their economic and physical security would be jeopardised were the project to be completed. The EU Commission has also expressed worries that Nord Stream 2 neither aligns with the energy and foreign policy interests of many of its member states nor complies with the bloc’s long-term strategy to achieve an Energy Union. Nord Stream 2 “could impede the development of an open gas market with price competition and diversified supply to the EU,” the Commission wrote.

As the debate over the merits and drawbacks of Nord Stream 2 rages on, Germany continues to push forward – although not fast enough, in the eyes of some – with its Energiewende project, in which the country aims to both decarbonise its economy and stop using nuclear energy. To achieve the country’s goal of becoming nearly carbon-neutral by mid-century, Europe’s biggest economy will have to virtually phase out all fossil fuel use.

The federal government says that it aims to reduce its dependence on energy imports – for which increased energy efficiency and renewables expansion make an important contribution – but also that natural gas will make a “significant contribution to Germany’s energy supply over the coming decades.” It points out both that gas is a cleaner alternative to oil and coal and that flexible gas-fired electricity generation can play an important role in balancing out fluctuating renewables feed-in. [Read more in the CLEW dossier The role of gas in Germany’s energy transition.]

When asked in a parliamentary inquiry by the Green Party about how Nord Stream 2 aligns with decarbonisation targets, the federal government did not give a concrete reply. It named Germany’s goals and wrote: “How the profitability of Nord Stream 2 would develop against this backdrop is first and foremost for the pipeline investors to assess.”

“Germany’s international energy policy will continue to aim to diversify energy suppliers and transport routes as much as possible,” the government wrote in its 6th energy transition monitoring report. In the reply to the Greens’ inquiry, the federal government wrote in May 2018 that Nord Stream 2 “as an additional supply route for natural gas from the Russian Federation contributes to improving natural gas supply security in the European Union.”

The German government also says that the pipeline is in line with the goals of article 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, namely ensuring supply security, promoting the interconnection of energy networks, and ensuring the functioning of the energy market.

Even if the project does eventually benefit Germany economically and in terms of climate protection, many argue that the country may have to grapple with concomitant damage by alienating many partners. In the words of Kirsten Westphal, an energy analyst at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs: “In commercial terms, there is a case to be made for Nord Stream 2. In political terms, however, it is clear that Germany will pay a heavy price.”

Journalism for the energy transition

3 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.