Six months after the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening started, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk by just over $400 billion, less than 10% of its massive expansion in the post-covid era when it nearly doubled in just days $4 trillion to $7 trillion, and then grew another $2 trillion over the next year.

Digging a bit deeper into the balance sheet composition, we find that high-powered money-equivalents, i.e., reserves, are just over $3.1 trillion, while the far more inert reverse repos (which are a byproduct of extremely excessive liquidity creation and/or counterparty and risk avoidance) are a more modest $2.13 trillion…

… with reserves declining by $1 trillion in the past year, as reverse repos actually increased by half that number.

And while one can debate the nuances of an $8.5 trillion Fed balance sheet, or the reserve/reverse ratio relationship until one is blue in the face, one thing is certain: now that the world has been in an “ample reserve” framework since the launch of QE1, there are certain things that are not supposed to happen: one of them is the use of the Fed’s emergency USD swap line. If, however, such an instrument is used, as was the case in mid-October, we can immediately deduce that some bank is suffering a crushing USD-funding squeeze (one whose risk is greater than the risk of being slapped with the stigma of using a FX swap). That’s precisely what happened with Swiss bank giant Credit Suisse, which we subsequently learned was being crushed by an $88 billion bank run, and only the secret backdoor bailout of the SNB and the Fed kept it solvent (preventing a far greater financial crisis).

Another instrument that should never be used in an ample-reserve world, is the Fed’s Discount Window: this “archaic” secured rescue loan arrangement, one in which banks obtain emergency liquidity from the Fed in exchange for loans, is a legacy of the pre-Lehman era, when its mere usage was enough to spark a terminal bank run for any recipient bank. One can argue that the launch of QE was specifically designed to reduce and/or eliminate the use of the discount window by US banks (after all, the post-2009 tidal wave of Fed-created reserves effectively assures that every US financial institution is swimming in money). That, together with the famous “discount window stigma” effect when the mere speculation one is using emergency loans from the Fed was enough to spark a bank run, is why there were zero discount window borrowings until March 2020 when the entire financial system almost collapse again, yet when a relatively modest $50BN in discount window borrowings forced the Fed to unleash multiple daily multi-trillion repo operations, and hundreds of billions in daily and weekly liquidity injections in the form of QE. Yes, the discount window usage in 2020 quickly faded away but not before the Fed’s balance sheet doubled again, from $4 trillion to $8 trillion.

The problem is that if one fast forwards to today, the discount window is again being used aggressively, and in the last week was just over $6.2 billion, after peaking at $9.5 billion, two weeks ago, the most since June 2020.

The spike in Discount Window usage has even stumped JPMorgan whose rates strategist Teresa Ho wrote last Friday (her full must-read thoughts available to pro subs) echoed our thoughts above on the “Ample reserve” framework, noting that “there are still over $3tn of reserves and over $2tn of cash at the Fed’s ON RRP, so in no way does this suggest there are systemic liquidity concerns. Indeed, that wholesale funding rates have remained well-behaved even heading into the final weeks of the year suggests as such”, and yet “it is surprising that in spite of the available amount liquidity in the system, usage at the discount window still increased. Borrowing at the discount window is often seen as a last resort for banks in terms of sourcing funding, and hence there is an implicit stigma associated with it. Whether that stigma is justified or not is an open question.”

Some more details from JPM:

This year’s uptick in the discount window is associated with primary credit–available to banks that are in “generally sound financial condition,” with no restrictions on the use of funds borrowed under primary credit according to the Fed. The loan must be collateralized with eligible securities (generally investment grade or AAA for securitized securities) and/or loans (generally performing, to domestic entities only). In March 2020, to encourage the use of the discount window, the Fed narrowed the spread of the primary credit rate relative to the general level of overnight rates and extended the line of credit up to 90 days, prepayable and renewable by the borrower on a daily basis. Since then, the primary credit rate has been set at the upper bound of the fed funds target range.

So what’s behind the spike in discount window borrowings? According to JPM, there are several theories.

The first revolves around increases in funding pressures among small banks as QT continues in the background. To that end, it’s possible that, regardless of stigma, to raise liquidity, some small banks are finding rates at the window economically more attractive than either accessing the fed funds market or borrowing from FHLB, particularly if they are able to borrow term at the discount window. Indeed, the primary credit rate was set at 4.0% (pre-FOMC), which was 17bp above EFFR but 30-70bp below where they can borrow in 1m and 3m FHLB advances. Furthermore, JPM notes that the timing of the increase appears to have been somewhat correlated to the crypto market, particularly in November after news of the FTX fallout emerged.

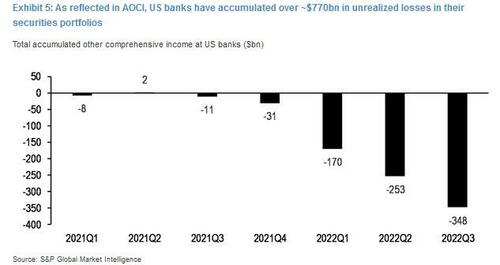

There is a second plausible theory: this year’s aggressive Fed tightening has generated substantial losses on banks’ securities portfolios. As reflected in AOCI, where changes in the market value of bonds in AFS portfolios are captured, US banks have cumulatively lost ~$770bn YTD (Exhibit 5). These losses, while unrealized, have significantly reduced banks’ equity, and in some cases reduced to a level such that tangible common equity has fallen into negative territory. This is the case particularly among smaller banks. Based on S&P data, JPMorgan found that ~30 banks, most of which have total assets of <$1bn, reported negative tangible common equity as of 3Q22, an increase from 11 banks in 2Q22, and 0 banks in 1Q22.

Why does this matter? Well, as JPM explains, FHFA currently has a requirement that directs FHLBs to use tangible equity–which includes unrealized gains and losses on AFS securities–in assessing a bank’s credit worthiness for purposes of issuing advances. In the event that a bank does not meet the required tangible capital levels, it could be denied access to the FHLB advance system unless a primary federal regulator says otherwise. (As a side note, the industry is trying get FHFA to amend the assessment framework from using tangible capital to regulatory capital, which would exclude market swings). As a result, to the extent the small banks need liquidity and they cannot turn to the FHLB system for borrowing, they might have to resort to the discount window for sudden, unexpected liquidity needs.

Translation: there are ~30 banks that are effectively insolvent and are only kept alive thanks to the Fed’s emergency funding. Whether or not these banks fail, and whether their failure leads to a cascade of adverse events, remains to be seen. Unfortunately, absent a chain of defaults which reveals who the crippled banks are, we won’t know for sure the entities behind the discount window spike until the Fed releases transaction data on the discount window two years later.

Finally, it is also worth noting that the substantial losses on banks’ securities portfolios – thanks to the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes – are creating not only capital issues, but potential liquidity issues as well. As we have discussed previously, with QT occurring in the background, liquidity is being drained from the system, deposits are declining (albeit predominately at large banks so far), funding pressures are gradually rising, and borrowing costs are increasing.

To the extent sudden liquidity needs arise, there is a question as to whether banks would have to sell their securities to meet their liquidity needs, which in so doing would negatively impact banks’ capital levels. Also, LCR is calculated based on the market value of banks’ HQLA portfolio as a percentage of their net cash outflows under 30 days. All else equal, losses on banks’ securities portfolios would contribute to a deterioration in LCR (i.e., the numerator shrinks). As a result, banks would have to lever up to increase their HQLA to remain compliant with LCR rules. Here, JPM believe this has been one of the reasons contributing to the rise in FHLB advances this year. That is, banks have been raising liquidity via FHLBs not necessarily because they have lost liquidity and need to replace it, but rather in anticipation of potential liquidity needs in hopes of not having to sell their securities and to maintain/improve their LCRs.

If all that sounds like a lot of financial jargon, then please ignore it – unless the discount window usage spikes again in coming weeks, it is likely that whatever event prompted one or more banks to quietly demand a bailout from the Fed, will pass. On the other hand, the message sent from the spike in discount window usage is ominous: no matter how one spins it, it suggests that as many as 30 small banks are now insolvent, and could represent the weakest link that – like the relatively small Terra/Luna implosion cascaded to the collapse of FTX and the wholesale deleveraging of the entire crypto ecosystem – leads to an violent and painful deleveraging of the entire US financial system.

The full must-read JPM note available to pro subs in the usual place.

Loading…