Today’s Capital Record episode with guest Aswath Damodoran helps explain the emptiness of ESG.

Few institutions on the right have been as committed to exposing the danger of the modern ESG movement as National Review Capital Matters. In fact, today’s episode of the Capital Record features my interview with Aswath Damodoran, a leading academic in the field of corporate finance and valuation who has become a fierce critic of ESG (a form of “socially responsible” investment that measures companies against environmental, social, and governmental benchmarks). A few points I find worth highlighting for those interested in a deeper dive on the subject:

- The claim that ESG comes at “no cost” — that investing in a way that meets these environmental, social, and governance tests involves no trade-offs — ought to ring some alarm bells. Basic laws of economics tell us that there is no such thing as a free lunch. As Damodoran puts it, “constrained optima cannot beat unconstrained optima” (this should be so elementary to any first-year business student, it hurts). It would be one thing if ESG zealots were claiming that although we have to accept lower returns or more difficult business conditions, it is worth it in exchange for the alleged environmental, social, and governance benefits that investing subject to ESG constraints will provide. But alas, that’s not what most of them have been saying. Instead, they claimed they would make the world a better, more “sustainable” place by forcing restrictions on others, and that no sacrifice would be involved. These intelligence-insulting claims are a great place to start one’s critique.

- But on top of the pretense that the law of trade-offs can somehow be ignored, there is an even bigger problem, given that this is an agenda effectively designed to reshape the entire economy: There is absolutely no agreement on what ESG is measuring, doing, or solving. Ambiguity and incoherence are hardly rare phenomena, but they generally do not attract trillions of dollars of capital, with ramifications to match. We are seeking to redefine the entire parameters of business with absolutely no consensus on what the aim or standard is.

- It would be impossible to define the aim of ESG when we cannot even define the “ESG” of ESG. What do we mean by environmental standards? By what tactics? When we force Exxon to sell certain fossil-fuel business lines, are we lowering carbon emissions, or merely transferring the operation of those carbon businesses to another operator (and almost certainly, one with far less safety and clean-energy capacity than Exxon)? Who gets to define what is “social” good? And what exactly is the “G” there for? Do we believe the Silicon Valley darlings of ESG indices practice good “governance”? Good for whom? This is a massive movement that has absolutely no clarity around the morals and standards that define it, yet it operates with the zeal and religiosity of an ecclesiastical denomination.

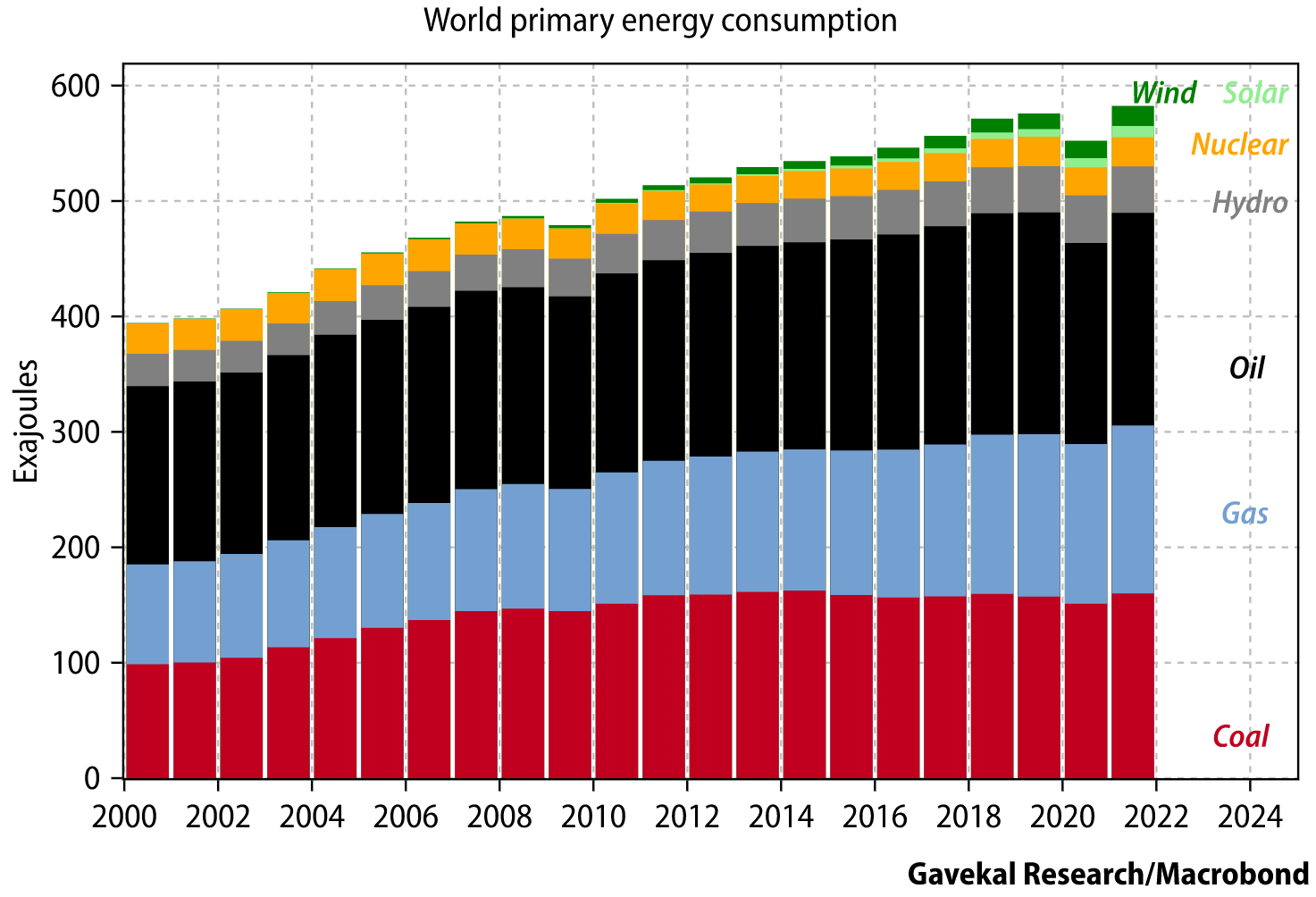

- If much of the “E” is centered around reducing carbon emissions, is it possible that it will do more harm than good? Would we have more renewables in the future without hampering the cause of capital formation at those companies most equipped to develop renewable strategies? Attempted central planning in one country is not going to make a difference globally, and so far, it hasn’t. Renewable energy, despite decades of green-policy investment across at least the Western world, has barely made a dent in fossil-fuel use worldwide, as the graph below shows. The reason: If something can’t happen, it won’t.

5. Fundamentally, and I cannot say this emphatically enough, ESG is a pharisaical way for people to feel virtuous and good without having to do anything at all. The lack of individual sacrifice being made by those who push so hard for ESG is damning. The sacrifices that are being made are being made by the shareholders in the companies (or the underlying shareholders in the funds that invest in those companies), now expected to measure up to ESG’s standards. Virtue is not something exhibited at no cost to the individual; agency, sacrifice, and cost are part of character and justice. The ESG movement has put the cost on other actors, abusively so, and feigned progress and moral superiority.

I encourage you to listen to the podcast with Professor Damodoran. The ESG movement is beginning to falter, and that is not merely because of a bull market in energy and bear market in Silicon Valley. An intellectually and morally bankrupt movement is finally being exposed, and the entire economy will soon be better off for it.

Source: Nationalreview.com