The recent damage to the Nord Stream pipelines is yet another twist in the saga of Europe’s energy crisis. Accusations of sabotage flowing freely between Russia and the West stand in stark contrast to the stunted supply of natural gas.

While neither pipeline is actively transporting gas to the continent, the ruptures add to an increasingly tense stand-off, even within Europe as policymakers mull how precisely to intervene to alleviate the pressures of high gas prices and prepare for a winter without Russian gas.

Here are five charts from BloombergNEF on Europe’s path ahead.

1. No Russia, no problem?

Russia has squeezed its supply of gas to Europe in recent months, with flows via the key Nord Stream 1 pipeline having been halted since the end of August. Amid the prospect of the Kremlin turning off the taps completely, Europe is faced with the question of whether it will have enough gas to make it through the upcoming winter.

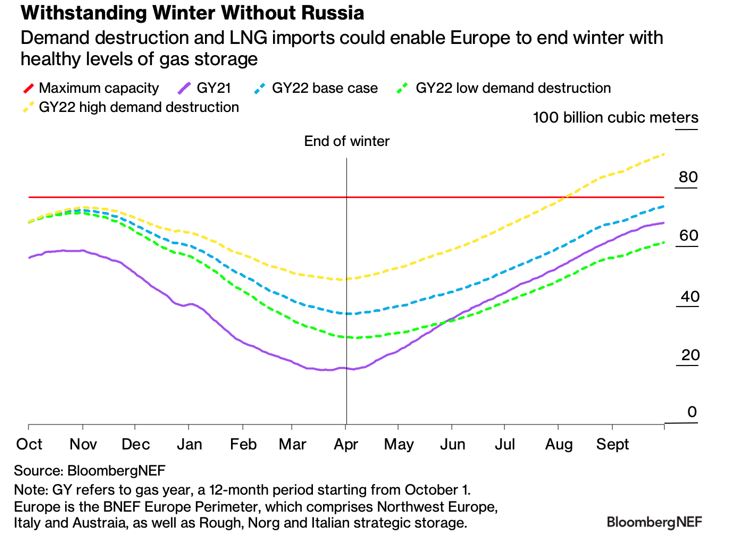

Contrary to widely held fears of an impending shortage, it looks like the region will be able to withstand a Russian gas cut-off, if – and it’s a big if – elevated prices drive sufficient demand destruction and also enable it to attract a high proportion of spot liquefied natural gas flows.

Under BNEF’s base case, total gas demand in the “Europe Perimeter” – Northwest Europe, Italy and Austria – is forecast to be around 17% lower this winter than the 2016-2020 average, if the weather is in line with the 10-year norm. With this level of demand curtailment and assuming no Russian gas arrives in Western Europe from October 1, storage in the Perimeter would end winter with more than enough breathing room at 37 billion cubic meters, or a healthy 49% full.

Even in a worst-case scenario, in which there is no piped Russian gas and low demand destruction, BNEF estimates Europe would still have enough gas to endure the coldest winter of the last 30 years without depleting its inventories.

Looking further ahead, the region could be well-positioned for winter 2023-24 as well. BNEF’s base case sees the Perimeter almost completely refilling its gas storage next summer to 94% full by November 1 – above the European Union’s 90% target.

On top of reduced demand, this outlook rests on Europe continuing to outcompete Asia to secure adequate spot LNG. While Europe has benefited from buyers in Asia being deterred by high prices, the tussle for cargoes could intensify if Asia sees a colder-than-normal winter or hotter-than-usual summer. Europe is set to become more reliant on the spot LNG market as more than 8 million metric tons worth of contracts expire in 2023, increasing its pull on flexible supply.

2. Demand destruction is key

Demand destruction is essential to Europe making it through the winter without Russian gas. However, there is considerable uncertainty over just how much demand will be eroded – such high and sustained gas prices have never been seen before, and at the same time, policymakers are exploring ways to both curtail demand and shield consumers from high prices.

The projected 17% reduction in gas consumption this winter under BNEF’s base case is slightly higher than the 15% cut targeted by the EU as part of its “Save Gas for a Safe Winter” plan. The drop is mostly attributable to residential and commercial users.

Residential consumers account for approximately 40% of winter gas demand in the Europe Perimeter and small changes to their behavior could have a sizable impact on the region’s gas balance.

“Reducing heating temperatures by 1 degree Celsius could save around 6% of this demand,” says Stefan Ulrich, a European gas analyst at BNEF. “In fact, households could likely turn down their heating by even more given that average EU thermostats are set at more than 22 degrees Celsius, some 3 degrees Celsius above the now-recommended level for public buildings.”

As well as wearing an extra layer or two, reducing the amount of time that heating is switched on during the day and optimizing efficiency could also save significant amounts of energy.

“All in all, reasonable actions taken by households and commercial buildings could reduce total Perimeter gas demand by up to 10%, but possibly even more,” says Ulrich.

3. The long-term plan to ditch Russian gas

Looking beyond the pressures of the upcoming winter, the European Commission has laid out how the bloc can end its dependence on Russian fossil fuels in the longer term in the form of the REPowerEU plan.

Building upon the Fit for 55 package, the new strategy envisages the EU more than halving its gas consumption across this decade and diversifying its supply via biomethane, LNG and other pipeline flows. The aim is to be weaned off Russian gas by 2027.

The ambitious gas-use cuts hinge on scaling wind and solar power, with REPowerEU increasing the bloc’s 2030 target for the share of renewables in the energy mix from 40% to 45%.

This feeds into wider measures to lower the gas consumption of buildings through heat pumps and improved energy efficiency, accelerate the production and deployment of green hydrogen, and delay the phase-out of coal and nuclear power plants.

Germany has already revived 8.8 gigawatts of coal and lignite capacity to reduce the need for gas-fired power generation, and Italy has brought 2.3GW of coal back online. In the short term, the return of coal is expected to boost emissions from Europe’s power sector both this year and the next, which would make three consecutive annual increases.

4. Renewables ramp-up needs more support

The EU Commission estimates that 780 gigawatts (GW) of solar and 510GW of wind power needs to be installed across the region in 2030 to meet the objectives of REPowerEU. However, while renewables build in the EU is expected to grow, spurred on by the energy crisis, BNEF currently forecasts only 343GW of solar and 625GW of wind capacity will be deployed by the end of the decade.

Making up that solar shortfall will require countries to accelerate their plans relative to previously set targets.

“Fortunately, this shouldn’t be too difficult,” says Jenny Chase, head of solar at BNEF. “From January to August 2022, China exported over 60GW of modules to Europe, presumably on orders from buyers. We expect only about 41GW to be actually built this year due to bottlenecks in labor and other components, but the interest is there.”

Chase points out that governments need to “work to debottleneck planning, permitting and grid connection processes to make more large solar projects feasible at suitable sites.”

It’s a similar story for wind. “Long offshore wind development timelines make it difficult to boost capacity quickly, while accelerating onshore build will require streamlined permitting,” says Oliver Metcalfe, head of wind at BNEF. “Governments are looking at ways to speed up these processes, but progress has so far been elusive.”

5. High power prices to linger

As Europe continues to rely on gas to generate electricity, high gas prices have translated to record power prices and the peak may be some way off yet.

Taking Germany as an example, BNEF doesn’t see the average wholesale power price maxing out until 2023 – at €275 per megawatt-hour ($270/MWh), from around €209/MWh in 2022. As well as high gas prices, upward momentum is anticipated from tight coal supply and lower electricity imports due to an ongoing shortfall in hydro and French nuclear output.

The good news is that German power prices are forecast to fall to €70/MWh by the end of the decade thanks to the rapid deployment of wind and solar, and an expected rebalancing of the gas market. The decline is even faster and further when accounting for the country’s new “Easter Package”, which seeks to frontload the build-out of renewables this decade.

Still, in the long term, power prices are projected to rise through to 2050, hitting around €90/MWh, due to the saturation of intermittent renewables, reliance on gas plants for dispatchable capacity, and increased power demand from the electrification of transport and heating.