The world is not divided between “democracies and autocracies”. Washington’s approach to China is dangerously confrontational. The Ukraine conflict is about getting Russia to the negotiating table. Unilateral sanctions are not legitimate. The United States is instigating a trade war against Europe. NATO should stop opposing European defence.

To say that France doesn’t see eye-to-eye with the US on most topics would be a serious understatement. Yet, during last week’s high-profile state visit by French President Emmanuel Macron to “his friend Joe” in Washington, both partners put on a great act, giving the impression they were living in the land of milk and honey.

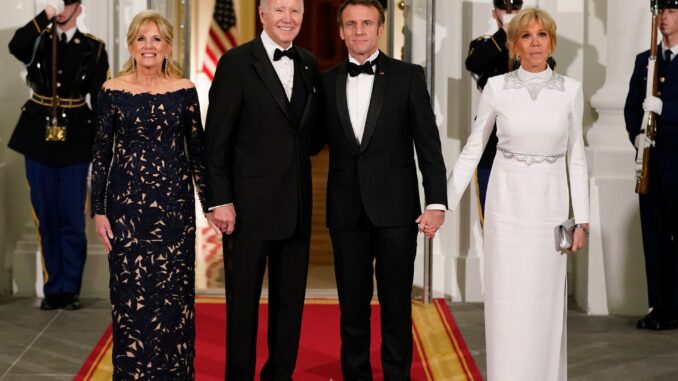

President Biden should be credited for pulling out all the stops. He arranged for “his friend Emmanuel” to have the first state visit of his presidency, a distinctive honour for France. Amidst much pomp and regalia, we were carefully treated to long displays of chumminess between the two leaders, including effusive backslapping and a friendly dinner outing in DC with their spouses.

At a joint press conference, Biden even seemed to have made efforts to curb his notorious propensity for droning on out of consideration for Macron’s time in the limelight.

There were also a couple of meatier morsels for French diplomats to go home with as proof that they had held the line of being “allied but non-aligned” with the US, and that they had pushed Washington in the right direction. Biden stated that he would be ready to meet with Vladimir Putin to end the Ukraine conflict, a reversal of his earlier position and a nod to Macron’s efforts to keep diplomatic channels open with Russia’s leader. Since then, the White House has signalled that the conditions were “just not at a point” for such a meeting to take place yet.

The US president promised to look at what he called “glitches” in his signature multi-billion Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which significantly hurts the European electric vehicle industry through “buy American” restrictions and massive state subsidies to US companies. A day earlier, the French president had denounced the package as “super aggressive” and posing the risk of nothing less than “fragmenting the West”.

Their joint communiqu? painstakingly listed the two countries’ shared positions on everything from Ukraine and the security of Europe to Iran, the Middle East, climate change, “the importance of African voices in multilateral fora” and a commitment to strengthening the global financial architecture.

But there was one notable omission: How to deal with China, which Biden has identified as the biggest threat to US interests and security.

“China represents the most consequential challenge to the global order and the United States must win the economic arms race with the superpower if it hopes to retain its global influence,” the current US National Security Strategy states. If that’s indeed the case, surely it should figure in a statement meant to demonstrate the closeness between Washington and Paris?

Except, the approaches of the two countries couldn’t be further apart.

While the joint communiqu? does mention “China’s challenge to the rules-based international order”, it only states that the two countries have pledged to “coordinate their concerns” – an indirect acknowledgement that they are currently anything but coordinated. This shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Paris has always been highly suspicious of the Biden doctrine that defines the present era fundamentally as “a contest between democracies and autocracies”. Viewed from France, this black-and-white framework is seen as overly ideological, geopolitically inapplicable and transparently self-serving. “A lot of people would like to see that there are two orders in this world,” Macron stated during a trip to the G20 in Indonesia last November. “This is a huge mistake, even for both the US and China. We need a single global order.”

It is no secret that France and several other European countries have been less than enthralled by what they perceive as Washington’s overly aggressive stance towards China, including the escalatory rhetoric about a possible conflict in the Taiwan Strait.

It’s not that France has any illusions about the inescapability of the rivalry between the world’s two biggest economies, or about China’s hegemonist moves in the Indo-Pacific in recent years. But Paris believes that differences should be managed within the existing multilateral framework, and aimed at lowering, not heightening, tensions.

At the G20 summit, the French president stressed that China had clearly distanced itself from Russia over time and could play an important mediating role in the Ukraine conflict. He also stressed that Beijing was committed to the existing world order and that President Xi Jinping shared his commitment to the United Nations – a transparent rebuke to the US position that systematically casts Beijing as a revisionist power intent on displacing the West.

The following day in Bangkok, Macron’s comments were even more pointed: “We are in the jungle and we have two big elephants, trying to become more and more nervous,” he told the audience. “If they become very nervous and start a war, it will be a big problem for the rest of the jungle.”

France has long been a proponent of a multipolar order in which big powers balance each other and agree to play by common rules. This suits both its traditional Gallic diffidence towards US hegemony and France’s self-perception as a “middle power with global influence”, according to the famous expression coined by Hubert V?drine, a former foreign minister. “We don’t believe in hegemony, we don’t believe in confrontation, we believe in stability,” Macron had told his Asian audience last month.

To Washington’s ears, it may have sounded self-serving, but the reality is that for most of the world, this is a much preferable alternative to a new cold war between two economic and military hegemons.

The public show of bonhomie between Biden and Macron can’t hide those deeper tensions. Their teams have hailed the French president’s visit to Washington as a success. But in terms of addressing the biggest risk factor in international relations – the possibility of escalation between the US and China – the results were of a far more modest kind: the big nothing burger.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.