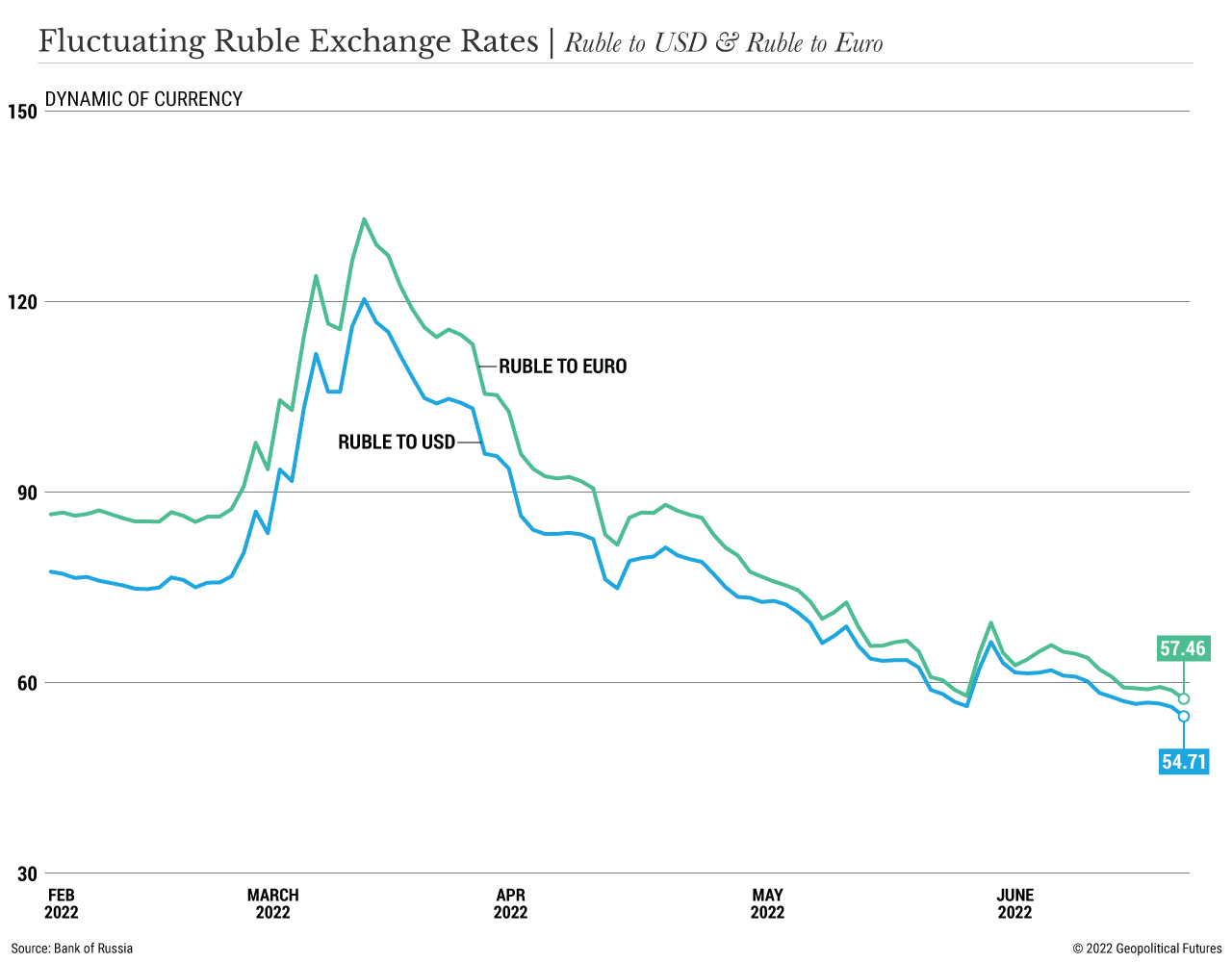

After a precipitous fall at the beginning of the war in Ukraine and the imposition of large-scale Western sanctions, the Russian ruble has surged back over the past two and a half months. From 120 rubles per dollar on March 11, the currency is now valued at around 55 rubles per dollar, and banks can buy dollars for as little as 44 rubles. But a strong ruble does not necessarily mean a strong economy. On the contrary, the ruble’s strength, combined with government and bank policies to limit the impact of sanctions, may complicate life for ordinary Russians more than sanctions.

Impact on Average Russians

Western sanctions against Russia since Feb. 24 have shredded supply chains, and many foreign firms opted to leave the Russian market, whether due to moral outrage or because of the difficulty of executing financial transactions. The list of sanctioned individuals has expanded, and many Russian banks – mostly state-owned – have been disconnected from the SWIFT international payments system. But the measures so far have had minimal effect on Russian consumers, who can find Russian or other foreign substitutes for most products and can still use SWIFT to transfer money via some private banks. More important, Russia’s oil production continues to grow, rising by 5 percent in May compared with April.

However, the most important consequence for both business and individuals was in the financial sector, which has grappled with currency restrictions, sharp fluctuations in the ruble’s value and unpredictable bank policies regarding foreign currency. It isn’t easy to find alternative means to make online purchases from foreign websites, execute money transfers, manage foreign currency accounts or exchange currencies at prices and conditions comparable to those before the war. (I personally had to give up subscriptions to Netflix, Amazon, and some newspapers and magazines, simply because I no longer have the technical ability to pay for them. Of course, Russians immediately found loopholes, but the process is typically inconvenient and expensive.)

Another problem Russians are facing is that, despite the strengthening of the ruble, domestic and imported goods and services are not getting cheaper. In theory, a stronger ruble should reduce the cost of imported goods, but instead prices from March and April – when the ruble was at its weakest – have proved sticky. For example, before the war an iPad Air cost approximately $1,100; the price soared during the initial sanctions panic, and at the current exchange rate it costs $2,500.

Ruble Rollercoaster

Currencies are always very sensitive to geopolitical disruption. Russia introduced a floating exchange rate, meaning the Russian central bank does not directly assign the value of the national currency. The central bank can change the exchange rate only by indirect methods – for example, foreign exchange interventions – while market conditions primarily set the value. At the start of the war, the ruble predictably depreciated sharply. In addition to high uncertainty, many Russians rushed to the banks to buy currency or change existing savings, which further increased the exchange rate. The panic was one of the main reasons for the increased price of goods.

Today, the ruble is the strongest it’s been against the dollar since 2015. This is due to two main factors: high global oil and gas prices, and capital controls. The war, proposed and enacted embargoes on Russian energy, and the throttling of Russian gas supplies to Europe (the Kremlin blames sanctions, the West blames the Kremlin) have pushed up oil and gas prices. Natural gas prices in Europe exceed $1,450 per thousand cubic meters, and Brent crude is trading at nearly $120, the highest since April 2011. Prices are likely to remain high for quite some time.

Amid this backdrop, a huge influx of foreign exchange earnings from exports of high-price commodities strengthened the ruble and gave the Russian economy a boost. Russia’s revenues from oil and gas exports are at record highs. Income from oil exports reached 4.75 trillion rubles (approximately $90 billion) in four months, half the sum Moscow expected to make all year. Previously, this foreign exchange inflow was compensated by purchases of foreign currency by the Ministry of Finance and capital outflow, but because of sanctions there’s been a drop in demand for foreign currency for imports and investment.

Moreover, Russia is requiring foreign firms from sanctioning countries to open accounts with Gazprombank to pay for gas and converting the dollars or euros into rubles, equivalent to a 100 percent sale of foreign exchange earnings. According to central bank forecasts, Russia will run a current account surplus of $145 billion this year, 19 percent higher than in 2021.

Domestically, Russia tightened its foreign exchange controls and introduced temporary changes to foreign currency transactions. To maintain the ruble exchange rate and reduce inflation, the Ministry of Finance obliged Russian exporters to sell 80 percent of their foreign exchange earnings. (Now that things are more stable, the ministry has lowered that figure to 50 percent.) Temporary restrictions on buying foreign currency were imposed on Russian citizens too. Dividing countries into “friendly” and “unfriendly” governments – as Moscow has done – has dramatically complicated money transfers even from banks not under sanctions. For residents of Russia and non-residents from friendly countries, the central bank introduced restrictions in April – cross-border transfers could not exceed $10,000 per month, a figure that grew to $150,000 in June – but the policies of individual banks muddied the waters by implementing commissions for servicing foreign currency accounts, transfers and receiving transfers, simply because the demand for dollars and euros has fallen.

Paradox

In theory, a strong ruble benefits importers and consumers alike because it makes imported goods cheaper and more accessible. It would be good for Moscow too, since import substitution is a long process that needs to be as cheap as possible. A strong ruble, moreover, helps the Bank of Russia to fight inflation, which stands at more than 15 percent. And it should help lower the prices of imported goods that some sectors of Russia still depend on – which would reduce inflationary expectations, make money cheaper and support economic growth.

But the paradox of the ruble is that as it strengthens, imports do not become cheaper and inflation doesn’t fall by much. Annual inflation dropped only to 16.7 percent in June compared with 17.1 percent at the end of May and 17.8 percent at the end of April. Under the current batch of sanctions and the uncertainty of supply chains, prices aren’t dropping even with a strong ruble. Home builders are in no hurry to sell products at a low price, guided here more by the usual principles of trade than by sanctions pressure. Real household income, meanwhile, is expected to fall by nearly 7 percent, further reducing the purchasing power of ordinary citizens.

A strong ruble, then, is bad in the short term and the long term. Russia is a vast and unevenly developed country, the maintenance of which historically requires financing and redistribution of funds. But it has to have funds to redistribute them. Total budget revenues for 2022 are expected to reach just over 25 trillion rubles, including oil and gas revenues of nearly 4 trillion rubles, even as it keeps some $155 billion in the National Welfare Fund. Taxes ensure a steady flow to these coffers, a large share of which are taxes from oil and gas companies and proceeds from the sale of energy resources abroad. Moscow’s primary job under the sanctions, then, is not only to maximize import substitution and preserve the economic situation of the population but also to make sure there’s money in the treasury through the sale of goods abroad. With a strong ruble, this becomes more difficult. That’s because exporters’ profits fall when the ruble’s value relative to other currencies increases, meaning the value of Russian exports will also decline.

Put simply, the ruble is too strong, a sentiment shared recently at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Under tough sanctions but requiring large expenditures, a rate of 70-75 to the dollar is likely the sweet spot. Moscow’s job for the next half-year is to weaken the ruble, and the government is already discussing instruments that will allow the currency to return to the range of 65-80 to the dollar, like it was before the war. But Moscow understands that in the face of severe restrictions on the movement of capital, the ruble may continue to strengthen. The central bank and the government began to soften their plans earlier than expected, but so far it has had no effect on the ruble. In the face of sanctions pressure, it will be difficult to achieve demand for the currency at the same level as before the crisis. It’s an unusual case when a strong ruble, like a very weak ruble, becomes a challenge for the Russian economy.

Source: Geopoliticalfutures.com