When the Western Virginia Water Authority began exploring an upgrade to the guts of its wastewater treatment plant in 2019, engineers knew it would entail managing extra heat-trapping methane emissions.

Aware that flaring even more excess emissions is an environmental no-no, they contacted a fellow utility, Roanoke Gas Company, with a proposition.

Now, a joint utility proposal to harvest that “homegrown” biogas is wending its way through the state regulatory review process. It calls for capturing and treating the byproduct so it can be fed into a natural gas pipeline serving about 12,000 customers including a hospital, a medical school and several large companies.

If the State Corporation Commission (SCC) approves the plan before an end-of-January deadline, it will be the initial such endeavor imagined when the Virginia General Assembly passed energy legislation earlier this year authorizing innovative gas capture.

Tommy Oliver is vice president of regulatory affairs and strategy at Roanoke Gas, which serves about 63,000 customers in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Southwest Virginia.

“We’re proud to be the first gas utility in Virginia to take advantage of the statute,” Oliver said. “As the smallest publicly traded gas company in the United States, we’re the little engine that could.”

Overall, the company figured its new $7.7 million gas-conditioning facility would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 13,700 metric tons.

It’s one piece of a comprehensive anaerobic digestion treatment process. In a nutshell, here’s how it’s supposed to work:

Digesters already collect biogas that is emitted as a byproduct of bacteria consuming organic solids pulled from the wastewater. Refurbished digesters would increase that biogas volume significantly.

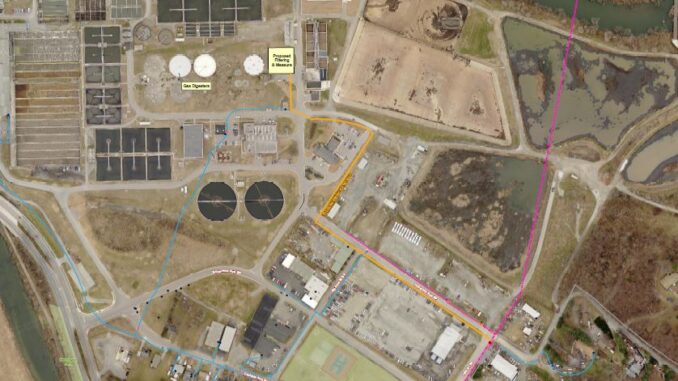

Constructing a digester gas conditioning system on the water authority’s property will allow Roanoke Gas to convert a product that is about 64% methane and 35% carbon dioxide to one that is 99% methane.

Initially, the system is configured to handle up to 280 standard cubic feet of digester gas per minute. That adds up to enough gas to fully heat roughly 300 homes on a cold day.

After that, Roanoke Gas has an option to invest more capital and proceed with a full buildout, which could handle up to 400 standard cubic feet of gas per minute, Oliver said.

“The water authority is using the gas to heat and treat the waste, but they were also flaring a lot of it,” Oliver explained. “So, then all of that heat and energy was being wasted. We can use it beneficially.”

By blending the locally conditioned gas with what’s piped in from the Chicago region and the Gulf of Mexico, Oliver said it can save residential customers 4 cents a month on their utility bills in 2023. Large industrial customers could save about $7.25 monthly.

Oliver knows the environmental community is leery about recognizing the climate benefits of what’s known as renewable natural gas. However, he said his company is intent on reining in emissions of fugitive methane because it’s such a potent heat-trapping gas.

Indeed, the lawyers representing Appalachian Voices, the nonprofit environmental respondent challenging the project, urged the commission to deny the application in a response filed on Dec. 8.

Claire Horan, an associate attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center’s Charlottesville office, is representing Appalachian Voices on the SCC docket.

Appalachian Voices, which has members in the gas company’s service territory, has participated in this case to ensure that only cost-effective climate benefits are approved, she said.

“It’s easy to be fooled by a term like renewable natural gas,” she noted in an email exchange. “But not all projects involving biogenic gas are beneficial to the environment. That’s why it’s really important to examine the details of the specific project.”

State senator: A solution legislators envisioned

State Sen. Scott Surovell, D-Mount Vernon, championed the Virginia Energy Innovation Act via Senate Bill 565 as a solution to reduce the state’s dependence on gas generated by drilling or hydraulic fracturing.

In an Oct. 4 letter to regulators, the senator from Northern Virginia recommended they approve the project because it “will benefit the environment and ratepayers.”

“Because of the Senate’s vote today, we are one step closer to making Virginia a national leader in cleaning up greenhouse gas pollution,” Surovell said in a Feb. 17 news release about green-lighting his bill.

Republican Del. Israel O’Quinn, who represents part of Southwest Virginia, shepherded nearly identical legislation through the other legislative chamber with House Bill 558.

When signed into law, the General Assembly had set a 180-day limit for utility regulators to approve or deny biogas infrastructure projects. That six-month deadline began ticking when the Roanoke Gas docket opened on Aug. 3. A three-day online hearing concluded on Nov. 22.

Horan, the SELC attorney, wrote in a post-hearing brief that setting such a tight deadline is problematic because “legislators likely did not envision, in the typical case, an incomplete [and] inaccurate application and a discovery process extending like a trail of breadcrumbs.”

“The Commission should not allow the statutory deadline to stand in the way of a thorough and accurate analysis of the benefits of this Project, and that is not possible on the record as it stands today,” she stated.

She faulted Roanoke Gas for falling short on three specifics laid out in the statute. Chief among them was the company’s lack of detail to clearly show that a drop in emissions is reasonably anticipated, mainly because of poor calculations.

Andres Clarens, a University of Virginia civil and environmental engineering professor, pointed out those faulty assumptions in October testimony on behalf of Appalachian Voices.

The professor’s calculations estimated that the proposed biogas facility would reduce carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by, at most, 3,744 metric tons — far less than the gas company’s estimate.

Relatedly, Horan said, Roanoke Gas had stated that greenhouse gas emissions would drop by 11,534 metric tons if the biodigesters were refurbished but the gas conditioning facility was not built.

That indicates the climate might benefit more from the project being denied, she explained, adding that those benefits would come at zero cost to gas company ratepayers.

“The [Virginia Energy Innovation Act’s] purpose cannot have been to force utility customers to pay after-the-fact, for twenty years, for climate benefits that have already been realized,” she concluded.

Climate benefits questioned

Horan also cited two reasons the biogas project isn’t in the public interest. Thus, she advised commissioners to reject a proposal that offers few, if any, climate benefits, at a potentially exorbitant cost.

Even if Roanoke Gas submits a new application, Horan said, approval “should be contingent upon the Company showing non-trivial and cost-effective climate benefits with a reasonable degree of certainty.

“But the Company has not yet met that burden.”

In tandem, she said ratepayers shouldn’t be forced to bear a financial burden if a market-driven funding mechanism — renewable identification numbers (RINs) — doesn’t measure up to the expectations Roanoke Gas has set.

At the behest of Congress in 2005, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s federal agency created the RIN program to reduce carbon pollution mainly in the transportation sector.

Briefly, every equivalent gallon of renewable fuel is assigned a RIN so its origination, use and trading can be tracked. RINs, a type of currency, work in a similar fashion to renewable energy credits.

Roanoke Gas has hired a broker, Innova Energy Services, to handle the RINs and selling of the environmental benefits of the biogas as allowed under the renewable fuel standard.

An SCC staffer had voiced substantial doubts as to whether the gas company would even be able to generate revenue from the sale of environmental benefits of biogas.

Dan Cox, chief financial officer and founding member of the Renewable Natural Gas Coalition, countered those concerns.

“RNG produced using biogas from a wastewater treatment plant is a highly desirable RNG [resource] given that it has a low lifecycle carbon intensity, allowing end-users to demonstrate high levels of [greenhouse gas] reduction,” he told the commission in a Nov. 14 rebuttal.

Through 2021, renewable natural gas powered about 64% of the country’s vehicles that run on natural gas, he added, noting that there is significant remaining capacity in the transportation sector.

Despite that reassurance, Horan said RIN prices are too volatile because they not only vary not only year to year, but also continuously during any given year.

Falling short on RINs means “Roanoke Gas will have to recover the resulting lost revenue from captive ratepayers — and the effects will be significant,” Horan said.

John Warren, director of the state Department of Energy, included a caveat about RINs in a Nov. 11 letter that otherwise supported approval of the Roanoke project because it “represents an innovative approach to generating affordable and reliable energy while also realizing environmental benefits.”

Due to RIN eligibility issues identified by SCC staff, “it would be appropriate for the Commission to require further confirmation from the company in this area before granting approval,” Warren wrote.

‘Great project all around’

While Appalachian Voices called for commissioners to reject the current application, the nonprofit didn’t dismiss it as meritless.

Horan mapped out three specific changes the SCC should undertake so the biogas project is more palatable to overarching climate and ratepayer needs.

Briefly, she recommended crediting all RIN revenues to Roanoke Gas customers, imposing a 20-year performance guarantee for gas production, and reworking provisions with the water utility so the digester rehab program achieves the level of leakage reduction and biogas volume claimed by the gas company.

Roanoke Gas challenged the need for those changes in a Dec. 8 post-hearing brief filed by attorneys with Richmond-based GreeneHurlocker.

The project is in the public interest, primarily because it will reduce emissions of planet-warming gases, counsel wrote, with the “majority of the reductions … in the Roanoke area, which will improve the air quality and livability of the Roanoke Valley.”

Numbers attorneys included in the post-hearing brief showed potential greenhouse gas reductions ranging from 5,200 metric tons to 13,700 metric tons, based on three different biogas throughput scenarios.

Roanoke Gas also maintains that its proposed plan to split RIN proceeds — 75% to customers and 25% to the company — is fair.

“Notwithstanding Staff’s misplaced concerns about the potential sale of RINs,” counsel wrote, “the only difference between the Company’s and Staff’s proposed revenue requirement and rates is dependent upon whether the Commission approves” the sharing arrangement.

Oliver, employed by Roanoke Gas for four years, is no stranger to the goings-on at the state regulatory agency, which hired him in 1989.

In November 2018, he retired as the commission’s deputy director in the Division of Utility Accounting and Finance.

He is delighted the biogas project would allow Roanoke Gas, in operation since 1883, to be a pioneer on two fronts.

“We would be the first in Virginia to sell this gas to our own customers,” he said. “And, we think we’ll be the first gas utility in the country to have this in our rate base. It’s a great project all around.”