I watched this stuff last time, amazed by the lack of inflation. Sure, “This time it’s different,” but those are the four most costly words on Wall Street.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

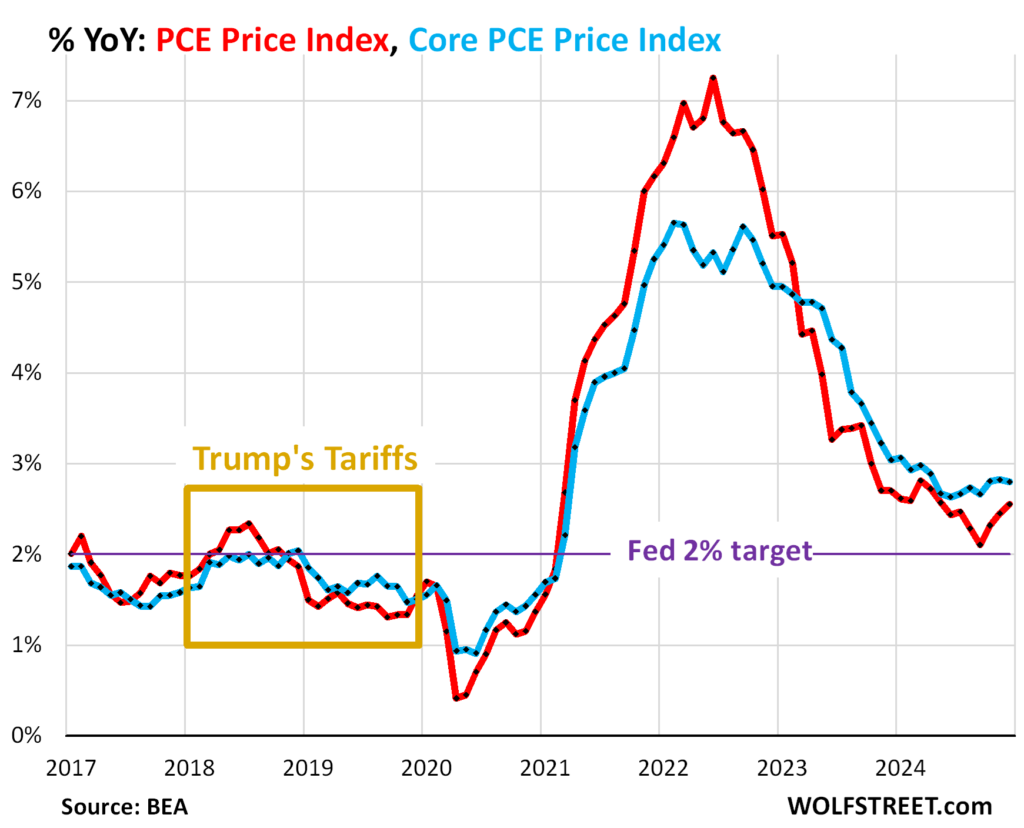

President Trump has now started implementing his promise to impose new or additional tariffs on goods from various countries, starting with China, Canada, and Mexico. Trump already imposed tariffs in 2018 against various countries. Now, once again, the media are all over how prices are going to jump for consumers because tariffs are a “regressive consumption tax,” and how tax receipts from tariffs won’t go up, etc. etc.

Now we’ll look at what tariffs did and didn’t do last time. One, they didn’t trigger inflation, which stayed below the Fed’s target. Two, they more than doubled tax receipts from customs duties. And three, they hit stocks, and the S&P 500 tanked 20% in 2018.

Sure, “This time it’s different” – but those are the four most expensive words on Wall Street.

Inflation did not accelerate.

We reported on the tariffs back then, also expecting price increases, thinking that companies would be passing on their increased costs. But that didn’t happen. They tried, but couldn’t. And the Fed-favored “core” PCE price index (blue) remained below the Fed’s 2% target and then decelerated further.

The reason that inflation remained cool and cooled off further in 2018-2019 was that durable goods inflation was essentially zero.

Tariffs are not applied to imported services; they’re applied only to imported goods. And those tariffs should have shown up in durable goods inflation because a lot of durable goods are imported, or their components are imported, and were tariffed.

The PCE price index for durable goods remained negative throughout that time…

…while the CPI for durable goods – CPI usually tracks a little higher than the PCE Price index – moved in a range of -2% to +1% year-over-year. The chart below shows the price level, not the year-over-year change, and it’s a little clearer about there essentially not being any inflation in durable goods at that time:

This lack of inflation in durable goods despite the tariffs throughout the period until the pandemic price spike surprised many of us observers. But there are reasons for it.

It’s hard for companies to raise prices and not lose sales. There is lots of competition in the US, including from domestic production. Companies, including retailers, raised their prices, but then lost sales and couldn’t sell at those prices, and their inventories piled up because Americans hate, hate, hate higher prices, and then these companies had to roll back their price increases in order to salvage their revenues. And in doing so, the companies and their suppliers ate those tariffs lock, stock, and barrel.

Customs duties more than doubled in less than two years.

Tax receipts from tariffs soared to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $80 billion in Q3 2019, from under $40 billion before 2018. The pandemic with its shortages and import hang-ups then mucked things up, but by Q1 2021, when Biden took over, customs duties were back at $80 billion and continued to rise through Q2, 2022, reaching nearly $110 billion.

This chart shows two things: One, the surge of customs duties under Trump. And two, it’s not something Trump invented. Customs duties had been collected before, and Trump just added to them, and they continued to be collected under Biden. Now the new tariffs will add to those customs duties already being collected.

We don’t know how much in customs duties the new tariffs will add to the existing customs duties, and the current amounts are not huge by government-deficit standards, but with the huge US government deficit, every $100 billion counts.

The stock market tanked in 2018. Tariffs are good for the US economy because they change the math for domestic production, and the primary, secondary, and tertiary effects of producing in the US are great for employment, tax receipts, household incomes, etc. But tariffs are not good for the S&P 500. Stocks got hit last time.

The reason why tariffs can hit stocks is because tariffs are a direct tax on Corporate America’s gross profit margins on imported goods.

But even for the S&P 500, new tariffs are just a one-time hit. So if the new tariffs cause a company’s gross profit margins to decline from 20% to 19% in 2025-2026, that’s it; they would not decline every year, but just once after tariffs are implemented, and then remain stable.

It’s not the end of the world for stocks. Crazy overvaluation is a far bigger problem for stocks. In 2018, QT-1 was also beginning to bite, and the Fed was nudging up its policy rates at snail’s pace. A mix of things came together in 2018, and the S&P 500 tanked 20%. But it didn’t last long.

Some basics about tariffs.

I posted this list before. But it’s important, so here it is again:

- Tariffs have two roles: raising taxes (which the US desperately needs); and changing the economic math for domestic production.

- US “trading partners” have used tariffs extensively to raise taxes and to protect and support their own industries at the expense of US production and exports. The US has used tariffs, they all have used tariffs to raise taxes essentially since the beginning.

- Tariffs are applied to the cost for the importer. If a big US retailer buys T-shirts by container loads from a factory in Bangladesh that it intends to retail in the US for $9.99 each, and if the tariff on this product is 25%, the importer (the retailer) is going to have to pay 25% in taxes on the cost from the factory. If the factory charges $1 per T-shirt, the tariff amounts to 25 cents.

- Tariffs are a direct tax on the profit margins of foreign producers and US importers. Whether or not they can charge more for their products without gutting their sales to pass on the tariffs is decided by the market. And if they can pass on a portion or all of the tariffs, it would be a one-time bump.

- Companies are already charging the maximum amount they can and still obtain their sales goals. If they raise prices to pass on the tariffs, sales may fall. Whether or not the retailer can raise the price of the T-shirt to $10.24 without pulling the rug out from under the desired sales volume is decided by the market, not by the retailer, and the retailer may find that it has to eat the tariffs.

- US importers may negotiate the purchase price to where the foreign factory eats part of the tariff, in which case foreign producers pay the taxes to the US government.

- Domestic production reduces transportation expenses, loss of Intellectual Property (a huge issue in China), supply-chain uncertainty and lead times (catastrophic issues during the pandemic), and other costs and risks. Tariffs tilt the balance further in favor of domestic production.

- Foreign manufacturers can avoid tariffs by producing in the US. All major foreign automakers that sell in the US already manufacture vehicles in the US. In terms of “US content,” Honda models are right behind Tesla on top of that list. Tariffs will further encourage US production, including of components and assemblies.

- Many producers have cut prices in the US over the past two years, either directly or through incentives to reach their sales goals, including automakers (here) and homebuilders (here). In this environment, they will eat 100% of any tariffs because they cannot pass on any additional costs.

- Industrial robots cost about the same anywhere. Products can be and are manufactured in the US price-competitively when advanced automation reduces the labor-cost component. Tariffs add some pluses to that math.

We give you energy news and help invest in energy projects too, click here to learn more

Crude Oil, LNG, Jet Fuel price quote

ENB Top News

ENB

Energy Dashboard

ENB Podcast

ENB Substack