Companies don’t just suddenly drop everything to stew in their own juices.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Look, the job market hasn’t cratered yet, and doesn’t look like it’s on a path to cratering, despite whatever is happening to federal government jobs and despite all the moaning and groaning in the media and social media about the cracks in the economy, the tariffs, the recession, or whatever. Companies are still doing what they’re supposed to do: taking care of business and chasing after opportunities. They don’t just suddenly drop everything to stew in their own juices.

Is Oil & Gas Right for Your Portfolio?

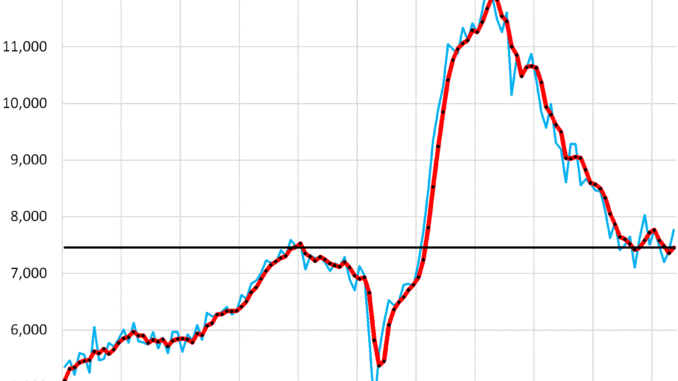

Job openings jumped by 374,000 in May from April, to 7.77 million, seasonally adjusted, the highest since November 2024, and the second highest since May 2024, and well above the high of the pre-pandemic Good Times (blue in the chart), according to today’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, based on surveys of about 21,000 work locations, and not on online job postings (fake or otherwise).

The three-month average, which irons out the month-to-month squiggles and revisions, rose by 96,000 openings in May from April to 7.45 million, right where it had been at the peak of the pre-pandemic Good Times, showcasing a solid labor market, but without the excesses of the labor shortages in 2021-2022 (red in the chart).

Most of these job openings are a result of workers having quit or having been fired, and leaving vacancies behind (more in a moment). Only a small portion of these openings represent newly created job openings.

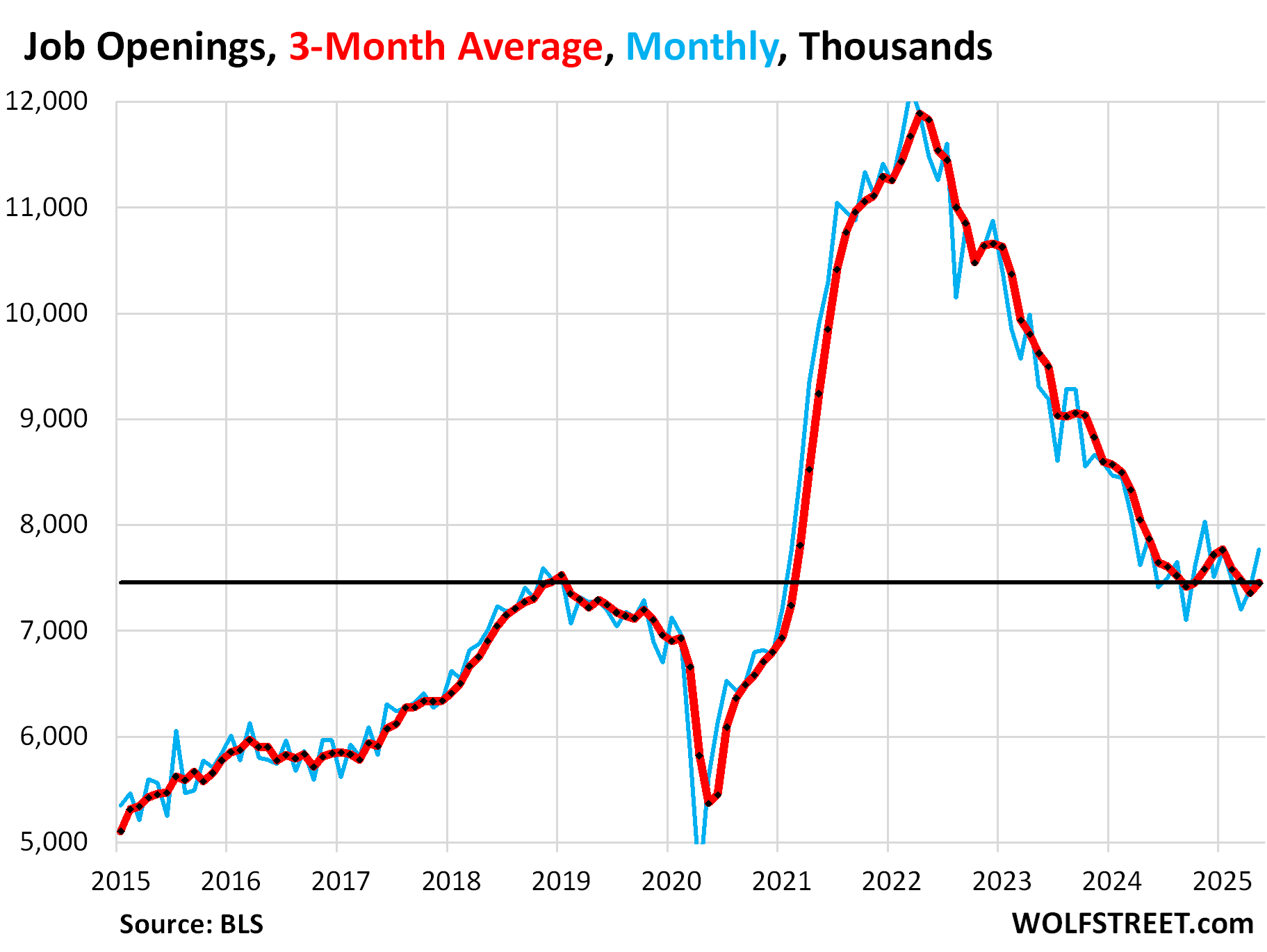

Layoffs and discharges fell by 188,000 in May from April, to 1.60 million, seasonally adjusted.

The three-month average fell by 60,000 to 1.66 million, the lowest since August 2024, and below the pre-pandemic Good Times low. The labor shortages are over, and companies are no longer clinging to whoever they could cling to, but this is a solid labor market.

These are workers who got fired with or without cause – a common feature of the US labor market – and workers who got laid off for economic reasons.

Excluded are retirements, deaths, etc.; they’re included in the small category of “other separations.” Also excluded are people who quit voluntarily to take a better job elsewhere; they’re included in “quits.”

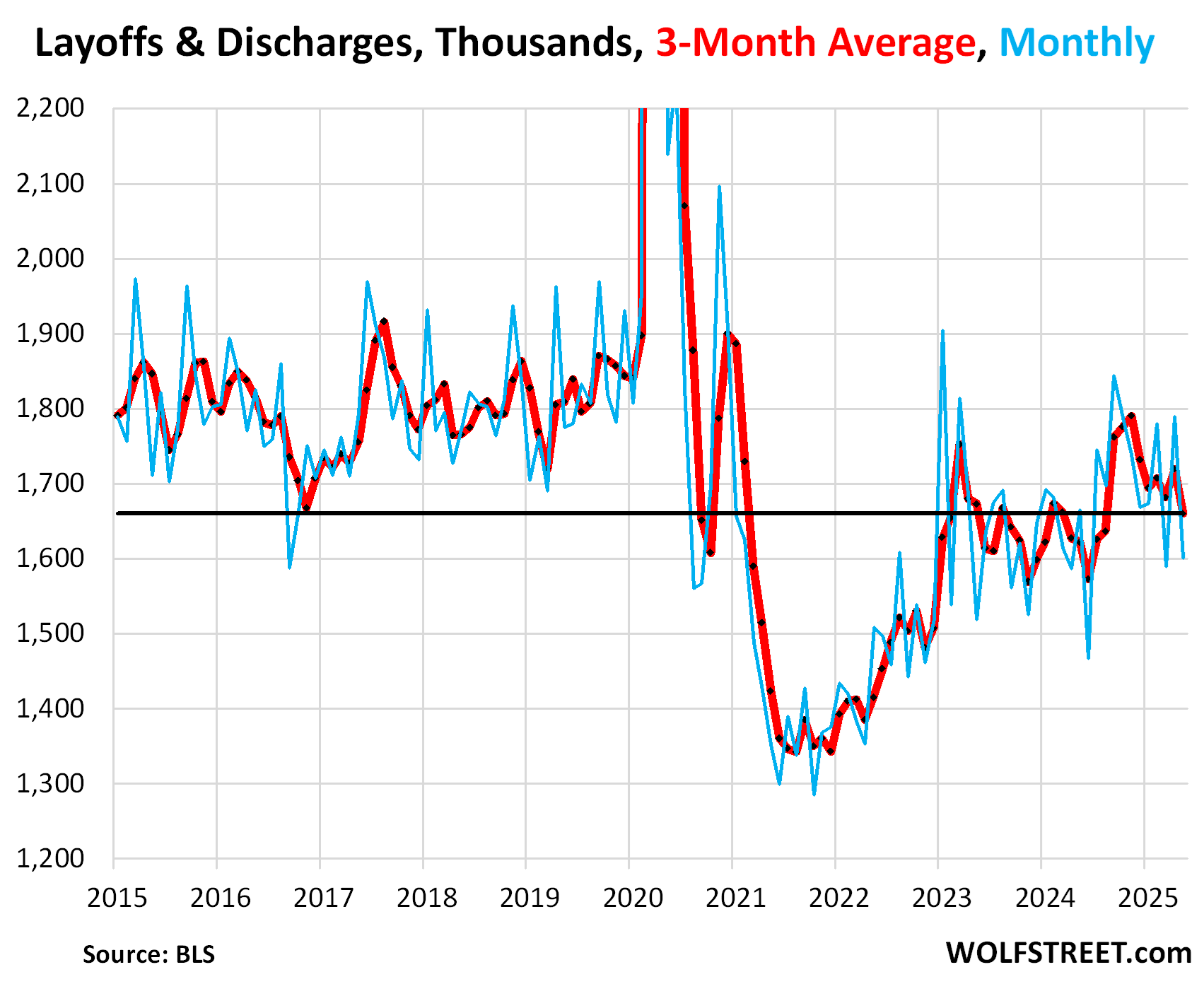

Quits rose by 78,000 workers in May from April, seasonally adjusted, to 3.10 million. These workers voluntarily quit their jobs such as to take a better job somewhere else. They do not include retirements, deaths, etc.

The three-month average ticked up by 14,000 to 3.28 million quits, roughly the same as in March. Both were the highest since August last year.

A high rate of quits is a sign of churn in the labor market. It means workers are unhappy where they are, and are confident they can find some greener grass elsewhere, or already have a new job lined up.

This still relatively low rate of quits, after the huge churn in 2021 and 2022, means that workers have found some greener grass elsewhere and that employers successfully scared workers into staying put with mass-layoff announcements starting in mid-2022.

Fewer quits means fewer job vacancies left behind, and fewer people that need to be hired to fill those vacancies. Job openings and hires are in part a function of quits.

Note the low point in quits towards the end of last year.

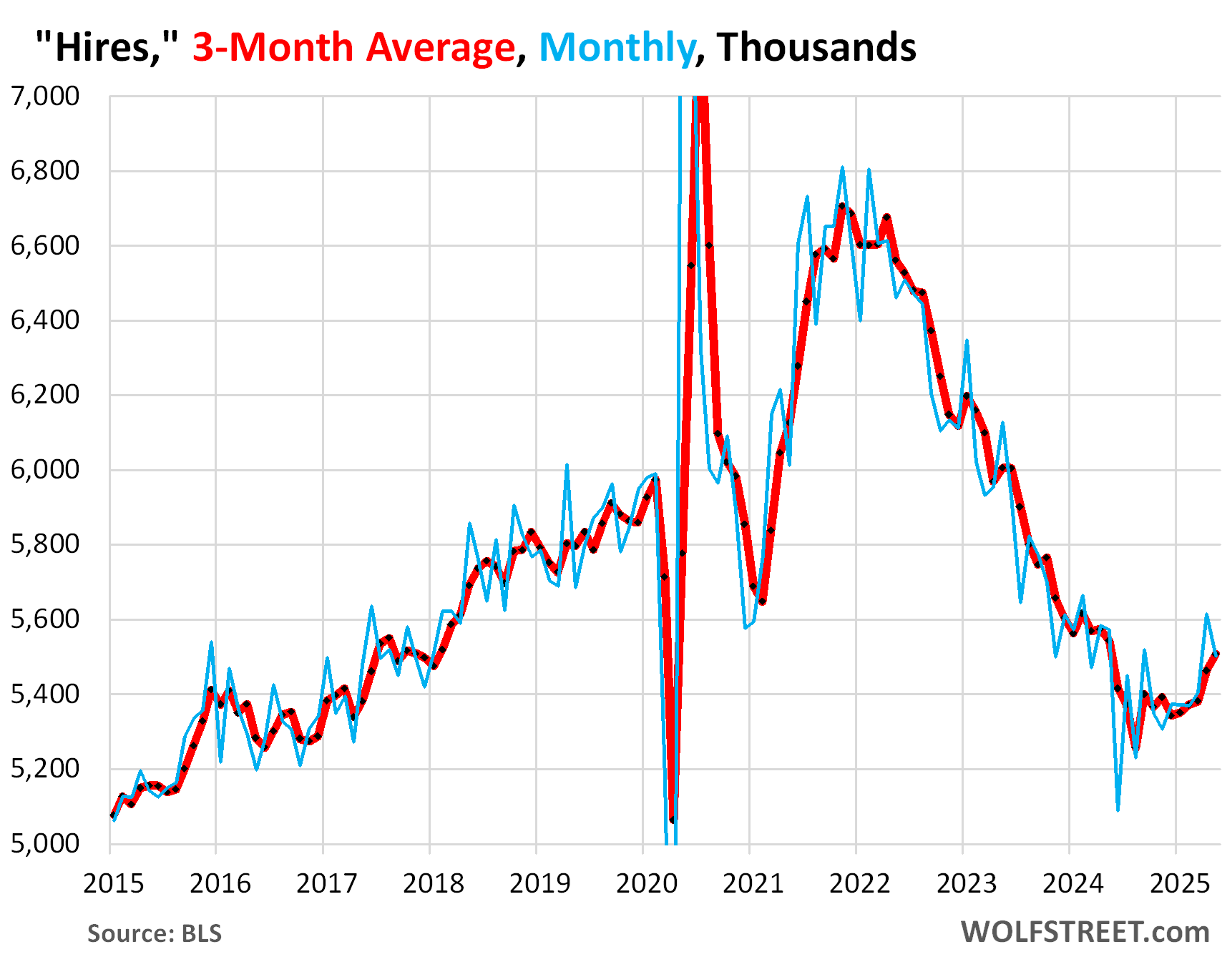

Hires declined by 112,000 in May from the spike in April, seasonally adjusted, which had been the largest hiring spree since February 2024. The total number of workers hired in May, at 5.50 million, was the second highest since September 2024.

The three-month average, jumped by 81,000 in May from April, to 5.51 million hires, the highest since May 2024, and the fifth month in a row of increases.

Most of these hires replaced workers who’d quit their jobs or who were discharged or laid off for whatever reasons. Only a small portion were hired to fill new jobs.

Fewer quits and fewer discharges mean fewer hires are necessary to fill the job openings left behind.

What we’re seeing here in these underlying data of the labor market is a solid and dynamic labor market, but without the immense and costly churn in 2021 and 2022, when people quit left and right to go after better jobs, when the whole labor market was reshuffled in a span of two years. What we’re looking at today are not the dynamics of a labor market headed for a recession; and so that recession stays on the back burner.