Nuclear and Financing – With Paul Tice

The world is in an energy-hungry stage, and we need nuclear, but how will nuclear be financed? The Energy Realities team, led by Author Paul Tice, has a comprehensive report on nuclear financing. In this episode, we dive into how new models could fund large-scale reactors and accelerate their rollout, while tackling the challenges that have stalled nuclear growth for decades.

With sharp insights from Irina Slav, Tammy Nemeth, David Blackmon, and Stu Turley plus David in rare form fresh off vacation—this discussion brings clarity to one of the most critical debates in the global energy future.

Download the entire paper here: http://energynewsbeat.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Tice.Nuclear-Power-Future.July-23-2025.Final-Proof.pdf

There are some critical parts in the report from Paul, and we recommend buying his book.

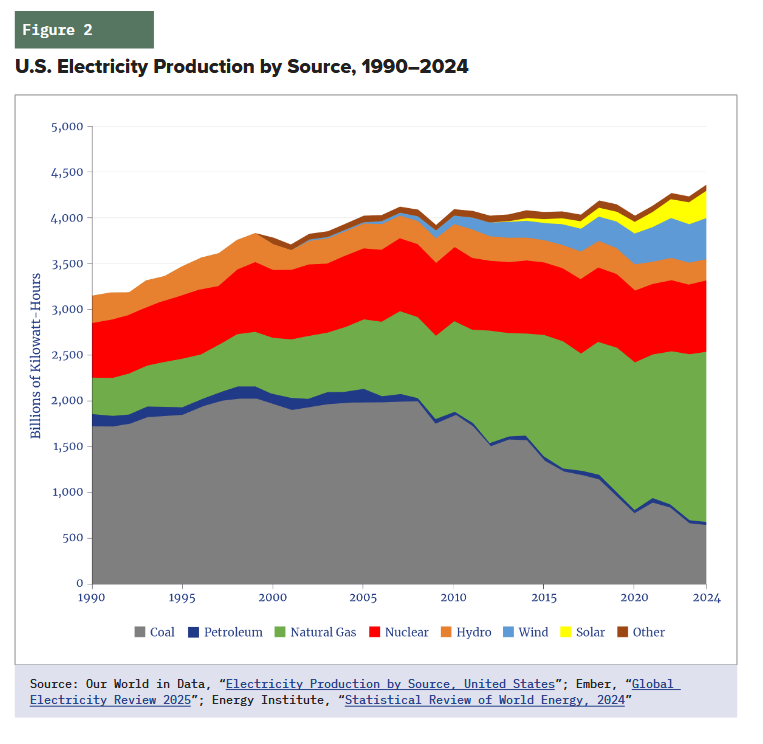

For all of the billions spent on wind and solar, they have been an “additive” rather than reformative.

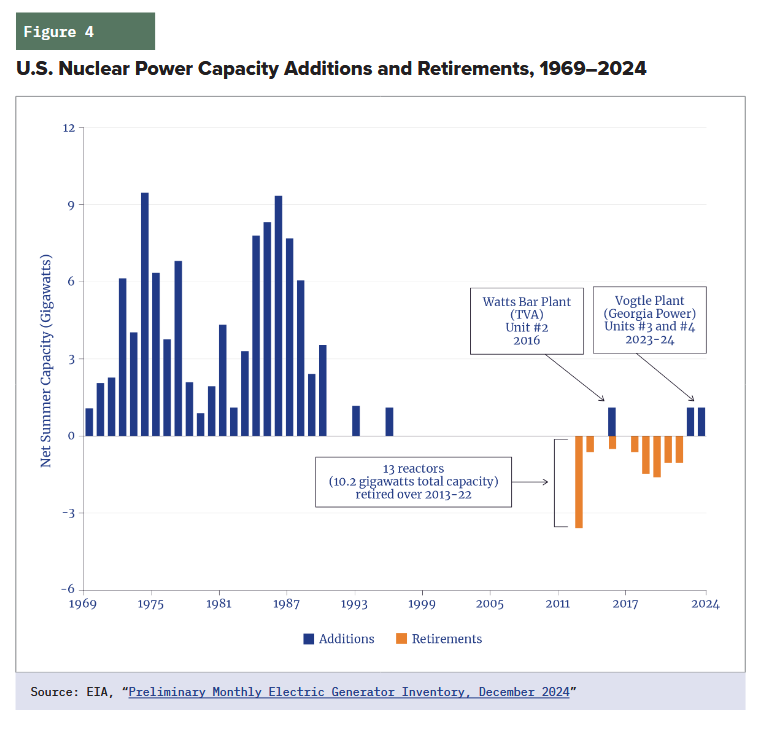

Tammy and Paul brought up some great points on Figure 4 and the lessons learned from the Vogtle Plants.

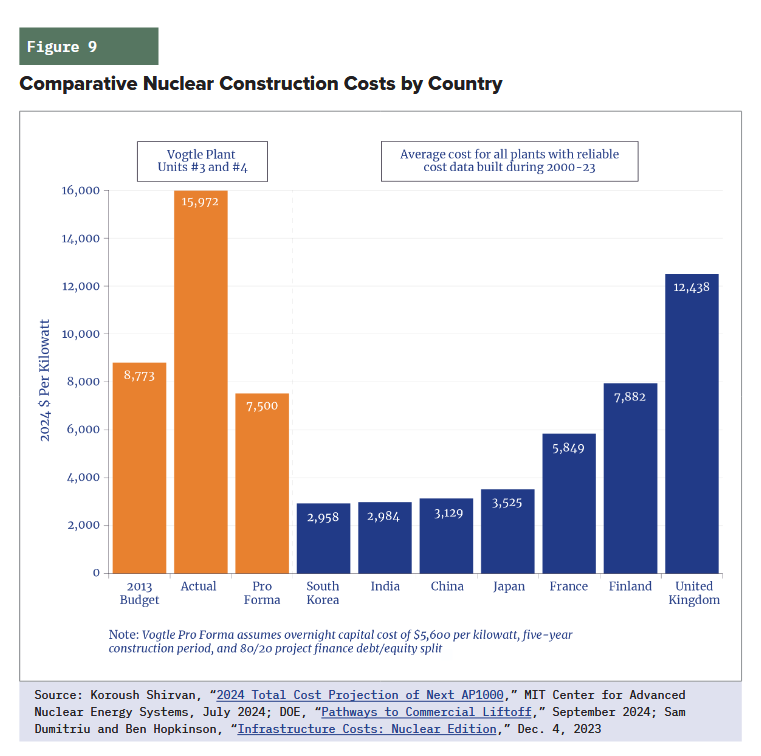

And when we spent some time on Figure 9 about the costs per country. China is ahead of the United States and is getting closer to exporting nuclear reactors as a service. This is how you build Energy Dominance globally by exporting reactors. You build a long-term client and revenue stream.

I am arranging for Paul to come on the Energy News Beat podcast and do a deeper dive on a few of the topics.

Thank you, Paul, for stopping by Energy Realities today!

Highlights of the Podcast

00:13 – Introductions

03:06 – Executive Summary of Nuclear Proposal

06:38 – Why Nuclear Development Stalled

11:27 – Nuclear Construction Costs Worldwide

14:21 – Cost of New Nuclear Reactors Today

18:11 – Regional Shifts in Nuclear Development

22:24 – Modular Reactors (SMRs) vs. Large Reactors

29:38 – Rising Energy Costs & Grid Strain

33:25 – Nuclear in Bulgaria

40:45 – Financing Models for Nuclear

52:29 – Federal Land & State-Level Regulation

57:07 – Private Equity Role & Future Path

59:30 – Closing

Nuclear and Financing – With Paul Tice

Video Transcription edited for grammar. We disavow any errors unless they make us look better or smarter.

Tammy Nemeth [00:00:17] Hello and welcome to the Energy Realities podcast. We have a full slate of people today. David Blackmon is back from his mini vacation. Hey David, how you doing?

David Blackmon [00:00:31] I feel tanned, rested, and ready to go, although I guess I’m just burned, not tanned.

Tammy Nemeth [00:00:39] That’s excellent. I heard you had a great time and didn’t get seasick even though you circumvented a hurricane.

David Blackmon [00:00:46] Yeah, we were kind of circling around Aaron the whole week last week in Bimini and a few other places, Dominican Republic, and had a lot of fun. It was just wonderful. And now I need to take two weeks to give my liver a rest before I’m full speed again.

Tammy Nemeth [00:01:04] Okay, we’ll go easy on you today. Hi, Irina. We have Irina Slav here today from Bulgaria. How are you?

Irina Slav [00:01:15] I’m afraid the weather is not as hot, autumn is coming and I’m happy.

Tammy Nemeth [00:01:20] Yay, not so hot. No. And maybe the forest fires will be under control. Yeah, it’s rain, so that should be all right. Yay. And we’ve got Stu Turley somewhere in, are you in Texas or Oklahoma today?

Stuart Turley [00:01:37] I’m back in Oklahoma after being in Texas last week, so you gotta love it. I’m looking forward to not being on the backhoe this week.

Tammy Nemeth [00:01:50] Hey, I’m sure all that construction work helps keep you limber and focused on being able to think about what’s happening over the news cycle, which is crazy these days.

Stuart Turley [00:02:01] Absolutely. That’s why I have a welder so I can try to put the stories together with a weld.

Tammy Nemeth [00:02:07] Awesome. And there’s me, Tammy Nemeth. I’m in the UK today. And we have a very special guest. We have Mr. Paul Tice, who is a senior fellow at the National Center for Energy Analytics. He’s also an adjunct professor at NYU Stern School of Business. He is a 40-year veteran of Wall Street and the author of this amazing book, The Race to Zero, How ESG Investing will to the global financial system. I think almost all of us have one. And so today, Paul’s here to talk to us about his super innovative proposals in his recent report, a strategy for financing the nuclear future. Hi, Paul, welcome to the program.

Paul Tice [00:02:51] Morning guys, it’s a pleasure to be with you guys.

Tammy Nemeth [00:02:56] So, Paul, just to kind of start out, can you give us like a real quick executive summary of your paper and what you’re proposing here?

Paul Tice [00:03:06] Sure, so there’s obviously been over the last year, I would say, even towards the tail end of the Biden administration, you know, more public support for nuclear, which is good. We have issues in the grid, obviously in terms of reliability, and we’ve pushed a lot of wind and solar, which are intermittent into many of the regional grids, including ERCOT, including up here at PGM, where I live in New Jersey. And eventually that’s gonna lead to problems when demand is not going to be growing one to two percent. It was fine over the last 10 to 20 years when electricity demand in the U.S. Was basically flatlining, right? But in a growing environment, clearly renewables don’t work, right. And so we had to get back to dispatchable sources of power and nuclear which has been dormant for decades needs to be part of that discussion. So there has been more public support for nuclear, Bye. That mainly is about SMRs, which are small and modular reactors. We haven’t built any of those, right? So that’s still kind of a science experiment to see if it works at scale and it’s economic. And then there’s also a movement to restart some of these morph ball nuclear power plants with PPAs from mainly the tech industry. But no one is actually talking about restarting large scale nuclear reactor construction. And so what’s the obstacle to that? And as we go through in the paper, I think the problem is the financial risk is just too extreme with regard to building a large nuclear reactor. And by that, I define it as greater than one gigawatt reactor. The perception is that it’s too financially risky. And the sponsors traditionally of nuclear reactor construction are electric utilities in this country. Right? So if they’re afraid to undertake it now, we need to understand why. And as we propose we think it’s time that we find a new class of sponsors who are better skilled to handle all of the financial and development risk at the front end of a nuclear reactor’s life and then probably turn it over to a utility to operate it for the next 75 years. Utilities are very good at keeping the lights on and and operating nuclear plants. They’re really bad if you go back over the last 60 years at building them on time and on budget.

Tammy Nemeth [00:05:34] That’s awesome, and an awesome summary. And I’m wondering, Stu, if you could bring up slide seven, which shows the… So on this chart, for the people who are just listening, it’s figure four in Paul’s report, where it talks about, it shows this graph of the US nuclear power capacity additions and retirements from 1969 to 2024. And there’s like this huge gap between probably around 1995 till about 2013 or so, where nothing was built. And so there was like this huge influx of nuclear power plants being built, then there’s nothing. And now we’re seeing retirements and there’s only been a few built since 2013. So Paul, why is there that gap there, that sort of drought of nuclear plants?

Paul Tice [00:06:38] Yeah, I think nuclear as an industry is unique in that you have not seen the normal development of any industry where they get better over time, they learn from the process, there’s a normal learning process which should lead to economies of scale and lower cost over time and quicker delivery. We’ve never seen that with the commercial nuclear space, mainly because of regulation, I would argue. You know, I think… The NRC has been, you know, safety concern to a fault over the years. And with every operating incident anywhere in the world, it has led to an overreaction in terms of their regulations and their approval process. So if you go back to the heyday of the industry, which was the 70s, you started in the 60s, into the 70’s, and then the 80s, we had Three Mile Island in 1979, when I was a when I was a teenager in high school. Long time ago, and you can see the overreaction by the NRC. So there’s another chart here we could talk about in a few more minutes, but in the 70s, the track record was pretty good for the industry about completing nuclear reactors, and these weren’t small reactors, they were close to one gigawatt in average size, and the average cost of completing them pre-Three Mile Island was less than $2,000 per kilowatt, and the averaged time was six years, right? Post Three Mile Island, the time to complete them doubled, mainly because of regulatory reviews, and the cost more than doubled. They went to $7,600 per kilowatt. And those are inflation adjusted, $20, $24, right? So something happened. So clearly I think regulation has been the main problem and that persists to this day. But after the 1980s, when we completed the last batch of reactors that were in the pipeline, And a lot of them were canceled right after Three Mile Island. So we would have had much more capacity now if we didn’t have that shock that occurred in the late 70s. And that was also obviously followed by Chernobyl in 86, which again, extrapolating out from a nuclear incident in the Soviet Union really has no relevance to the US. But that’s been the norm over the years. And any nuclear excuse to basically go negative on the industry, the environmentalists clearly have been there. As well as the regulators who should at a certain level be supporting the domestic industry. And in Fukushima in 2011, you saw that same reaction. And that led to actually, you know, countries, including Germany, opting to shut down nuclear reactors. So a very extreme response to what was basically a tsunami-related incident, right? So I think regulation is something that the Trump administration is addressing, and they need to really work on that. In order to kind of break some of these other ancillary log-gems that we have. But you know, the industry went dormant, you know. Starting in the 90s, we had an attempt under Bush, the younger, at a renaissance, right? They passed the Energy Policy Act in 2005. There were 31 orders for new reactors, large reactors. 20 years later, we only built two of Again, Fukushima happened after that last attempt at a renaissance. And then we also found out that the NRC was still a problem, right? Because even though they attempted to streamline the process by coming up with a combined operating and construction license, thinking that would make it easier, that actually made the change order process more rigid. And so it delayed it more. So, you know, the two units that were just completed in the last two years, right, so. You know, 20 years they were originally planned. Back in the 2000s, and we just completed the only two new generation reactors down in Georgia in 23 and 24, right? And those came in at the highest cost ever on an injustice basis. So that sticker shock I think is playing through a lot of people’s minds within the industry. Certainly the people that hate nuclear are using it to their advantage to say it’s cost prohibitive to of nuclear in this country. Even though it’s being done in other developed countries at a much more efficient rate. So I think we need to analyze exactly what’s gone wrong. Regulation would be a big start. And then also I think, you know, the sticker shock from Bogle is something we have to really get behind because I don’t think we’re going to get electric utilities to step up at this point and in the paper we go through all the issues around why.

Stuart Turley [00:11:27] Paul, this is an outstanding paper, by the way. And I don’t mean to be nice to you on a Monday morning, but holy smokes, Batman, look at this bad dog. This chart is comparative nuclear construction cost by country. And for our podcast listeners, you take a look at what you were just talking about, the Vogel plant at 15. Thousand nine seventy two per kilowatt and you take a look at south korea india and china and they’re all in the three thousand to three thousand dollar range holy smokes batman you know you take look at the ua e which i came in i believe around the five thousand dollar range. I have to go fact check that one. But France is at 5,000. They have roughly, I believe, 50 some odd reactors, but they’re only capable of running at about 50% because of their maintenance issues. They stripped out their maintenance over the past several years. Look at the United Kingdom. They’re right up there with the US. Way to go, United Kingdom, follow the United States, woo! Holy smokes, that’s a lot of money.

Paul Tice [00:12:53] Yeah, I think I think the UK has the same problems that the u.s. Has in terms of Government regulation, I I think there’s probably more antipathy towards nuclear over in Europe. I think that’s fair Tammy and arena can tell me if I’m wrong there, but you don’t be You know the countries that have lower the cost and the completion time are those that haven’t had an arrested development of the industry. The government has been very supportive. Korea would be a good example. China, obviously, because the entire economy is government related. So when you have government support, including financial support, and you don’t have government regulators getting in the way, you know, it tends to lead to better execution. And with any large infrastructure construction project, time is money. So if you double the completion time. It’s going to effectively double your financing cost, right? And that’ll be embedded in the final cost. And you saw that with Vogel, right, it was originally both those reactors, which were AP-1000, the Westinghouse design, and we’re arguing that we need to be more, to build more of that specific reactor design, because we’ve already built it. We’ve learned from Vogel if we’re willing to acknowledge the lessons there, and we need build what we know, right. We can’t spend any more time de-risking other reactor designs, whether large or small, because we’re just going to lose time then, right?

David Blackmon [00:14:21] Paul, we have a couple of really good questions from viewers here. One from Tom Butz, with inflation impacts, do we know how much a new nuke would cost? I guess in the U.S. Is what he’s asking about. What’s the average cost today, do you think?

Paul Tice [00:14:40] Well, the, you know, just extrapolating out from Bogle, if you want to go back to this one, this is levelized cost here, but if you go back, right, so this You know the The orange chart which Stu was focused on with the

David Blackmon [00:14:57] Keep going. No, not that. It’s the one where you had the UK and the US about the same level. Where is that?

Paul Tice [00:15:08] Right, so this is basically using inflation adjusted prices for all of the numbers shown here, right? So the orange is Fogel, the original budget, you know, the actual number that came in for both, and then a pro forma which would X out. All of the non-recurring factors that elevated the price of Vogel and we should go through all of the things that were non- recurring around the Vogel project which shouldn’t come into play down the road and then these are reported from other countries. We think the data is fairly reliable but again when you’re dealing with a country like China for example you have to take every number that they report economically or construction wise with a grain of salt but the delivery times are tougher to fudge. So there, clearly, they’re seeing better execution. So I think these are achievable numbers in the current inflation environment. I mean, there are bottlenecks that we have to basically restart the industry and build it up again, because it’s been more than a year since we completed the last unit at Vogel. And we don’t want to have that little expertise that we started to build out. You know, going overseas, because there are more AP1000s being built overseas than in the U.S. We have no orders right now, which highlights kind of the problem that we have in terms of everyone’s afraid to build one of these. So I do think the numbers that we have in the paper, which just came out two weeks ago, are achievable, you know with some wiggle room, right? You should be able to build a new reactor at an overnight capital costs, not including financing, somewhere in the range of $6,000 per kilowatt. And then if you embed on financing, and we think a project financing cost would still be cost effective, that gets you probably to 7,500 to 8,000 per kilowatt. I think anything under $10,000 per kilowatts, utilities would be fine with that. I think the regulators who would have to approve the purchase of that brand new nuclear reactor at that price would be okay with it. Again, it would be half of what we just spent on Bogle. And certainly, you can justify those economics if you look at a reactor that has an 80-year operating life that basically has a 95% capacity factor.

David Blackmon [00:17:27] And another one from Patrick Devine, with the dearth of nuclear plants since Three Mile Island, is there a silver lining being the shift in the national load centers beginning to shift more west than east? Could mean nukes being built more where needed now than in the past? And I guess the other part of that is when you get to the Midwest and Texas and you know, uh, not the west coast, but in between the two coasts, you’re looking at friendlier regulatory environments now as well, probably at least at the state level. So are you, do you foresee a shift, a kind of a regional shift in nuclear development in the future?

Paul Tice [00:18:11] Well, I mean, most of the population is not in the Plains area of the country. Right, yeah. So that’s a fair point. So I think we need to put, and that may be one reason why we’re not seeing a lot of data centers being put in Kansas or the Plain. Relatively, I think that’s true. You know, Virginia is very concentrated with data centers, you know, we have them up here in New Jersey. A lot of those are related to the financial industry over the Hudson in New York. So they may follow the load from these data centers, but I would argue that we shouldn’t have dedicated reliable energy, nuclear or otherwise, just for the tech sector. We can’t have a bifurcated grid where our data needs are 24-7 satisfied. And then the rest of us have consumers as well as other industries. Have to depend on a grid that has way too many renewables in it and has the risk of outages, kind of in Mad Max fashion, right? So we have to have, I think all the nuclear that we build should be used to firm up the existing grid, right. And I think it’s a good sign that some of the tech companies like Microsoft as well as Metta, when they signed the PPA, to restart a couple of these nuclear plants. It’s not a direct PPA. So they’re helping to restart it with their purchase agreement. But that power will go to firm the grid. They can claim whatever crazy zero emissions credit they want to with regard to their carbon profile. Whatever gets us to the right place, I’m fine. And I do think that we should see more support from. From the environmentalists and the climate activists are nuclear, right? I mean hands down it’s matchable zero emissions energy so it beats wind and solar you know any day of the week and you know if we could just dispel this rumor that it’s not cost effective and it’s prohibitively expensive which I think is easy to do then we should see others from the left joining on board. And I think the fact that the tech companies was clearly skew liberal in terms of their management, them being on board with nuclear, I think, will help. I think build some momentum there.

Stuart Turley [00:20:42] I just had a couple of interesting interviews with the CEO of a nuclear company as well as the interview with the folks that are really working with the Stargate data center. And I think modular reactors are going to help delineate nuclear into the big power plants, which I think we need. And I like, I love your phrasing of having the big nuclear plants stabilize the grid. But what I’m seeing, Paul, is that we’re seeing behind the meter is becoming very critical for businesses in the United States. And it’s either you pay for your own power and you pay for your own. Behind the meter services, modular reactors, several of them are planning on building 100 reactors the size of a truck, you know, every a year. So I think that that is going to be the way around the regulatory issue and get that cost per kilowatt hour down will the modular reactors. I don’t know how people are going to stomach paying for the big boys again, even though I think that that’s something that needs to be an export as a service. I believe the U.S. Has two Westinghouse orders potentially going into Poland. I need to go check that. I don’t know for sure.

Paul Tice [00:22:24] Yeah, no, there are orders overseas for the AP-1000, Poland, Bulgaria would be one. There are obviously four operating in China. I think they also have an order book there to add more units. But none here. Westinghouse has announced over the summer, I think it was back in July, that they would like to build 10 AP-1,000s here, but they have no order book for those 10, right? I think it’s a good sign and obviously. You know, their business would benefit from a reestablished U.S. Industry, especially since, you know Trump has put out this stretch goal of quadrupling our generation capacity for nuclear over 25 years. I mean we’re not going to get there, but the fact that we’re going to shoot for it I think is a very good thing. So and we’re gonna, you now, come close at all, we’re really going to have to get started on that. But I’m fine, you know, get all the above is fine as an energy policy with an asterisk, I think when it comes to the grid, it should be only dispatchable power, right? We need to stop coming up with a different standard for renewables. But with nuclear, you know, if SMRs are the approach for certain industries, you smaller reactors, I would be agnostic about that. I think that’s perfectly fair. I have a natural gas generator here because I don’t trust New Jersey’s transmission grid, right? A strong wind on a sunny day and my power is out for four days, right. Just, you know, don’t wanna have to deal with the food going bad all the time, right, so I think SMRs would be in that category, but still, again, we haven’t built any of these things. We’ve just approved like 10 new designs, new scale’s been talking for years, oh. Just wait, we’re going to build something. And until you actually build it, it’s just like a large nuclear reactor. You don’t know what the economics will be. I think the jury’s still out about whether it’s going to be a savings from a kilowatt.

Stuart Turley [00:24:27] Nanonuclear reactor founded by J.U., and I just interviewed James Walker, the CEO, and they have two locations already approved, one in Canada, one the United States, and their design is going to be for also ships as well as small modular nuclear for small cities and those kind of locations where they can drop them into coal plants. Know, and start going into data centers that way. They have their approval process going, working with Chris right now. And as they get them approved, they’re also getting their, they’re building not only the two new nuclear sites that they’re the test sites, They’re also building their factory at the same time. So for me that was what I was absolutely huge to hear that they’re building their factory at the same time so they can get mass production of these things.

Tammy Nemeth [00:25:32] Well, I think Paul’s point is, I think he’s accurate there. I think we have to draw a distinction between the hype and commercialization. So there’s a lot of hype right now where, like he said, there’s these 10 ideas. And Stu, your guys sound really interesting that they’re building this factory at the same time. But until you actually have it commercialized, like the big ones are already commercialized. How long does that take? And it’s one thing to say, okay, we did this in a lab. We got this great pilot project going, but it’s a big leap from pilot to commercialization. And who knows how long that’s gonna take. And I think, Paul, I think your point is that we don’t really have all that time. We already have this design that works. We’ve worked out the bugs. Why do we wanna set this aside? Why don’t we build more of this now that we’ve kind of worked out this, the problems.

Paul Tice [00:26:27] Yeah, and I think the other problem you have is that everyone’s got their own SMR design. And one of the faults of the industry over the last 50 or 60 years is that we have way too many reactor designs and bells and whistles. We have, right now, there are 94 operating nuclear power plants. At the peak, there were more than 100. We have 50 different commercial designs. So we’ve taken this diversification goal, which I think is important when you’re talking about a strategic asset like your nuclear power, and we’ve take it to an extreme. And I think we’re doing that now with SMRs because we’re approving what? More than a dozen probably, and everyone’s gonna be slightly different. And our ability to replicate that, even though they’re building a factory, which is good, that’s showing a commitment. But once they build the first couple of units, then we’ll know if there are problems with some of these modular components. With Vogel, they found out that they fabricated a lot of the components in a factory. And then once they had it on site, they realized they were problems. Their ability to rework those components was hindered by the fact that it had been done offsite. So that actually added to the delay. I’m not sure if they would be of the same scale problem that you have with SMRs. But it’ll be a learning experience. And I think that will delay the process. And it could elevate the cost. And the other thing, too, I made this point to Tammy the other day. Everyone loves SMR. And you don’t see the environmentalists really pushing back on it. But wait until we start actually building some of these things. And then we’ll see if they actually are OK having more nuclear assets even though they’re smaller. Spread out further across the country. I’m sure the backlash is coming there. But, you know, I think right now people are just waiting to see if that’s going to build any of this.

Stuart Turley [00:28:29] Paul, one of the big questions I have is talking to all the data center and AI guys that I’ve been talking to. I’ve had a few people that I got even in the pipeline here. Metta is constructing their 10 billion, four million square foot artificial AI data center. Holly Ridge, it’s gonna be natural gas. And your point of natural gas is on point. You can get them and stage them in in here. I love the way your thought process was on this paper, and that is we’ve got to get the finances fixed on these big boys. But I’m afraid the data centers are going to be hogs. They’re going to self-serving hogs, and I think that Metta is going to one of them because they’re just dropping this into Louisiana. And what, like New Jersey and back east, you’re seeing the inflation happening because of data centers of higher electricity prices caused by the demand.

David Blackmon [00:29:38] I think that’s overstated, don’t you? I mean, the electricity costs in the Northeast have been skyrocketing for 20 years now. And there’s a lot of different causes. They’ve really been…

Stuart Turley [00:29:51] They’ve really skyrocketed, David, in the last few months, like in New Jersey. Understand, but yeah, understand. New Jersey, they went from $600 to $1,000. Right, but offshore winds played a big role in that, and there’s a lot of factors. Let’s take New Jersey’s. New Jersey has nuclear and natural gas. Why are their prices going up? It’s because of the transmission costs. But they also have offshore wind.

David Blackmon [00:30:16] For they have promised exorbitant you know they’ve made commitments to exorbatant rates for those offshore wind farms under this governor anyway i’m sorry i don’t want to derail

Paul Tice [00:30:27] No, no, no. You’ve set me off, so I need to jump in on this. And I’ve written about it recently, but in New Jersey, my utility just raised my rates and everybody else in the state by 17 to 20 percent in June. And that is attributable to both problems here under Murphy, within the state, and our participation in PJM. For the last 10 to 12 years has gone from being one of the better run RTOs to one of the worst run RTS. Right? But here, as you say, if you care about emissions, we have almost an optimal mix of generation right now because it’s nuclear and natural gas. Right? And our natural gas is right next door in Pennsylvania. So, hey, call me crazy. Let’s build more pipelines over to Pennsylvania. You know, New York is shutting down their pipelines. Murphy has been shutting down pipelines that cross across New Jersey as well, right? And he’s wasted all this money on offshore wind, which has nothing to prove for it right now. All those projects have been canceled. And Orsted took a billion dollars of federal money that Murphy re-gifted out to them to keep them in their last project, which should have gone to subsidized rate payers in the state. So right now, we’re dependent on PJM because we can’t supply all of our generation needs because we shut down the last of our coal and we stopped building natural gas years ago, basically when Murphy came into power. And nuclear, like everything else in the country, has been in this condition of stasis where no one’s been adding capacity up until the recent talk. So we need to… I think New Jersey would be great to participate in the nuclear build out. We should build more natural gas. And I’ve argued we should probably get out of PGM, because they have the same problem on steroids that we have in New Jersey, because it’s a collection of more than a dozen blue states in the northeast. Maybe we’re just going to compound all of our climate policies together. And you’ve seen that with PGM. You know, they have a capacity market. What have they been let bid into it? Wind and solar, most of it’s been fictitious. The interconnects and the transmission requirements have delayed all of it, and they’ve allowed fossil fuels to be shut down over the same period of time. So, committed capacity in PJM has dropped sharply, and now we finally get the price reaction, right? 17 to 20% is not a normal, well-functioning market. So, pray for New Jersey. November when we have our

David Blackmon [00:33:19] Paul sounds like ice now when I talk about Irka.

Tammy Nemeth [00:33:25] Irina, I want to bring you into this. What was the reaction in Bulgaria amongst the people when they approved nuclear power? Like this Westinghouse one, which was signed, I think, just like a month ago.

Irina Slav [00:33:43] Did they? Well, we’re in polite company, so I won’t quote, but the price tag is much higher than it would have been if it had, you know, they had continued with the original plans because they have to take everything down and Westinghouse’s prices are just much higher. And we’re not happy about it because, I mean, we normal people, regular people, because we’re going you have to pay for it. And it’s a purely political decision. It’s not an economic decision, which is what most decisions of our latest dozen governments have been, which is why we don’t really like this. But we can’t do anything about it. I don’t know, are they going to start construction anytime soon? Because it could take years. Yeah. And it probably will. We don’t if this government will, you know. Live through a full term, four years, and who knows what the next government will be like and what will happen then. So I would understand if Westinghouse is in no rush to start work on this project.

Paul Tice [00:34:55] Is the current government, is the current government liberal or conservative?

Irina Slav [00:35:00] Oh yeah, it’s very pro-western. We don’t do liberal and conservative here. We do pro-Western and anti-Westerm. So the last few governments, none of which live to term, have been all very, very pro Western, but they haven’t really been able to do anything with long-term implications because they get overthrown in just a few months. This one might I think it might survive a year or a couple of years. We’ll see how things go next year when we adopt the euro because people are unlikely to be happy about this. So this may make such large-scale projects more problematic, even more problematic.

Paul Tice [00:35:50] Yeah. Well, I mean, if you’re not going to break ground on this, then, you know, there’s probably a risk that you could easily cancel it. So, um,

Irina Slav [00:35:58] Yeah, I think the European Union should pay for it because they made as close four of our six reactors and the two that they graciously allowed us to keep using are producing a lot of electricity that are keeping the lights on in most of the country.

Paul Tice [00:36:16] So they’ve made you, even though.

Irina Slav [00:36:18] Oh, yeah, it was a condition for joining the European Union. They were too old, they were too Russian. The two functioning ones are also Russian, but they’re perfectly fine. So they made us close them on safety grounds. There were no safety problems. I actually have a friend who works in an industry adjacent to the nuclear power plant. And I asked her, was there a chance to restart? At least a couple of the ones we shut down, she said that it’s not possible because they’re being shut down too long ago. So we are forced to build new reactors if we want more nuclear power. But at least we don’t have Germany’s problem with the environmentalist lobby and anti-nuclear mad men and mad women. I don’t understand. So at least that’s that, that’s good news. So whoever ends up building new reactors, there will be no such, you know, massive opposition from the population, which is good news, I think.

Paul Tice [00:37:28] Right. No, no, certainly is a two front war as far as right.

Irina Slav [00:37:34] Joanna had a good question, I think. If AI doesn’t provide its own electricity, doesn’t it mean we the rate payer will be paying disproportionately more for the power and transmission?

Paul Tice [00:37:48] Yeah, I mean more more load in general is going to stress the overall grid. So unless you have some of these AI users Having their own dedicated power Um, it’s going to stretch it and I think Policymakers need to take that into consideration, right? They can’t just again like like in pjm just allowing any capacity real or not to be bid in they can’t Just allow any you know million foot data center that’s going to gobble up power like a small city, if not a large city, to just come online. There has to be a gating function, I think, to that. Otherwise, everyone’s going to pay for it. I agree with that. So that’s another argument. If you want to push some of them to get their own dedicated power and keep it separate from the grid in order to minimize the cost to average ratepayers, I think that that should be part of the policy. Um you know there’s a lot going on we have to shore up the existing grid right because we’ve been asleep at the switch for at least 10 years now um really at every state that has a real portfolio standard i mean it’s been 20 years we’ve been pushing these dumb things even west virginia pushed it and didn’t realize that until 2015 after their coal industry was dead they finally got rid of their rps right so every state has it some to an extreme and and hopefully with what Trump and the DOE are doing now with the endangerment finding and dismantling a lot of the federal climate bureaucracy, the next step will be to push down through all the states, right? Get rid of all of these, you know, zero emissions targets or climate goals, right, and a lot of them have fed into the electricity grid. But we can’t have a by-forgetting grid, I agree with that, and the goal policymakers has to be had to minimize the average cost over time of electricity. And I think that’s having a diverse mix of coal, nuclear, and natural gas. And we shouldn’t just all do natural gas because it’s a thing we can build more quickly right now. Because down the road, we’re going to have to deal with higher natural gas prices, potentially. Which is part of the cost of electricity, because we’re gonna be exporting a lot more LNG. And our market is going to be more tied to the international market. And gas overseas is tied to oil prices. So we’re going to import a lot of that volatility. We can’t go all gas, right? Nuclear clearly is attractive. It’s only 8% of our capacity, and it’s almost 20% of our actual generation. So it has punched above its weight for years. We need to remember that. And I think we should start building coal plants again. I mean, if you really want to call out the whole climate argument, build another coal plant, right, that is also good baseload power. And then again, we’ve got three different streams, and that over time should minimize our exposure to supply chain issues and feedstock costs.

Tammy Nemeth [00:40:45] Yeah, those are all really great points. And I want to kind of tie it back to the whole financing thing, because one of the criticisms of the Vogel plants and why the cost was so out of control, you make a really good point in your paper and your report that if there had been this other financing mechanism, it would have reduced the cost because the way you describe it is Westinghouse. Which had never constructed nuclear power plants before said, yeah, we can do this. We can be the contractor and we can be the designer and we’re gonna do this all in one ourselves. But you’re proposing that private equity with dedicated infrastructure companies that have experience building large projects would be able to bring that cost down. Can you explain that probably a little bit better than I just did?

Paul Tice [00:41:43] Sure, but let me expand on some of the points about Vogel, because that is central to the whole argument that we can build nuclear large reactors on time and on budget. We just need to look past everything that was unique around Vogel. So it was the first time construction of the AP1000, first next generation design, first reactor we built in an actual generation in this country. Right? First time we built something going through the new NRC process with a combined construction and operating license. Right? So it was a learning experience for everyone, including the people at Georgia Power, which sponsored the project. You know, it’s not the same people that built unit one and two at Vogel, right? Those people that, you know, long since retired. And so it was a first of its kind from a number of perspectives. But as you mentioned, one of the big things that we’re not gonna have to worry about going forward is the fact that the EPC contractor for Bogle was Westinghouse. So they designed the reactor, I mean, they’ve designed most of the reactors in the world that are in operation right now. So they’re very good at nuclear reactor design, but as you said, they have never built a reactor, right? And so, you know, anyone who’s done a home construction project know you don’t want it to be a learning experience for your contractor. Right when he’s working on something and you have a Westinghouse and and they actually compounded the problem because they were building the two reactors at Bogle in Georgia and simultaneously they were doing two same-sized reactors in South Carolina for the South Carolina utilities so you have four 1.1 gigawatt reactors they were building simultaneously okay um you know and the regulators the company sponsors in Georgia as well as South Carolina. No one raised their hand and said maybe this is a problem so I think the due diligence was pretty poor all the way around right and not surprisingly we had a surprise delay at the front end of the process because the NRC changed its rules right um they approved the AP1000 back in 2005 In 2009, when these four reactor projects were going to FID, the NFC came out and said we need to change the plans because we have to make sure the nuclear reactor can withstand the commercial hit from an airliner right so that delayed us three more years right and then we kind of basically started in 2013 and what was found is that the change order process was very rigid there were almost 200 amendments for each of the Bogle units because they had constructability problems they had modular issues where they couldn’t fix some of the fabricated units on site, so they had to ship them back. Again, it’s all learning because this is the first time one of these things was ever built. And then, not surprisingly, with all the delays that were built into it and the fact that they went to FID without detailed engineering plans, which you never did. The cost just escalated. And Wesley House filed for bankruptcy, right? So, and their contracts were very rigid. So they had to eat a lot of the change orders. And so it’s not surprising that they filed. So anytime you have a contractor file in the middle of a construction project, you know it’s gonna be painful, right. And so that delayed it further. It doubled the time from five years, which was the original plan, to 10 to 12 years, right, cost went from, as I said, it was close to $8,000 per kilowatt. When the dust finally settled was $6,000 for two weeks. And then also we had COVID at the back end. So I think we’re never going to have another COVID situation. So you bake all that into it and explains away a lot of the cost overruns and delays around Bogle and why we shouldn’t have to deal with that going forward. But the sticker shock is there. What’s interesting, at the National Center for Energy Analytics, we do an annual energy conference that in Washington. It’s called the Energy Future Forum. And we sponsor it with real clear energy. And this past year, we did it with the US Chamber of Commerce. And we had the head of Georgia Power speak on one of the panels, or get interviewed, really. It was a form of fireside chat. And she was talking about nuclear and Vogel, obviously. And at the end, the moderator asked her the question. They said, any plans to build any more nuclear reactors in this country? And she just shook her head and said, no. And I think that just speaks to the problem we have because clearly Georgia Power knows the best about how you build these things and what went wrong and what to do right going forward. And they know that unit four came in better than unit three in terms of cost. And we started to see the beginning of an efficiency and learning process going from one unit to the other. And still Georgia Power has no plans, right? So I think with electric utilities, their track record is still poor. You have the Bogle headline still fresh in everyone’s mind. And I think the people who run electric utilities are fairly risk averse, right? So you’re taking career risk if you get this thing wrong, right? And we saw that with the South Carolina project. Again, that one was canceled that Westinghouse was building. So, 9 billion of capital was sunk into the ground there. Uh, Scanna, one of the sponsors there, they were so weakened by that, that they were forced to sell to Dominion, right? Uh, the head of the other utility had to step down, right. Some of their executives went to jail, right, for misleading regulators. I think a lot of that was scapegoating. Um, but even, even Georgia Power didn’t come out unscathed, right?. They were downgraded. Their bond ratings were downgraded because of financial stress. They were forced to sell their Florida utility to raise money to shore up the balance sheet. And so I don’t think any executive who’s at the tail end of their career, who’s doing an actuarial estimate is going to want to take that risk. So as you mentioned, we’re proposing a project financing and project finance has always been a way to mitigate risk, right? So if you’ll have a large capital project, do it off balance sheet, don’t risk the company. Which is what was done with Bogle, right? Georgia Power and Southern obviously were a stronger utility to start with, and they were able to weather even $35 billion total cost for those two reactors, right, but most utilities are not in the same position as Southern, I would argue. So project financing allows you to move all of that risk, construction risk and financing risk, off the balance sheet, do it on an asset-specific basis, but we need to bring in a better manager for the construction period. And we think that infrastructure, private equity, fund managers have all the skills that would allow them to succeed in nuclear construction and still achieve their targeted returns. So it’s all about making money. The fact that, you know, Wall Street and private equity investors have never done anything in nuclear is because it’s been very unattractive because of the open-ended construction risk, right? You will kill your economics during the construction phase if you get it wrong. You can never make that back. Right? So nuclear has been unique in that respect. But when you think about it, it’s not too different from building LNG liquefaction terms, right? Or plants, right. There’s a lot of capital commitment there. You know, there’s a lot of assets specific binary risk. So I think a lot that skill set is transferable. And project financing lets you raise a lot cheap debt. So that will allow you to put smaller equity checks into every project. Which will help you minimize your risk as a fund manager and we need the government to help out in terms of providing that debt option, which they’re already doing for renewables. So we’re arguing just repurpose a lot of that money, which obviously will no longer be going towards subsidies for other technologies. So we do think it could work, but I think the White House really needs to make the pitch. And this morning. The piece I wrote in the Washington Post kind of goes through that whole argument that Trump really needs to get out there and make the pitch to Wall Street about nuclear as an attractive investment, right? The economics can work. We go through that in the piece. They can still create these nuclear reactors at an attractive value for utility buyer while still making, you know, north of 20 percent returns, right. So we just need to get execution and we need to have a proof of concept. So another reason why we need to get a bunch of these projects going, and then I think it’ll feed on itself. The private markets will step in and solve problems that it’s given. So if you can prove that the first couple work. And the other important point about Vogel, we have final blueprints from Vogel. They’ve all been approved by the regulators. So assuming we can build that without making any more meaningful change orders for the next AP 1000s, the execution, we should not be surprised by anything on the regulatory side. And back to your question before, I think it was David about where do we build these? I would gravitate towards existing sites, right? We have nuclear plants, there are 21 in this country, the DOE came out with a report back in June, which identified nuclear and coal sites that actually would have room for an AP-1000. Right? We have 21 nuclear sites. Most of them are obviously skewed towards the east, because that’s where most of nuclear. Capacity currently sits. If you want to do a pure greenfield that’s fine. Definitely we should do something in Texas because I agree with your you know your issues around ERCOT. But coal also we’ve mothballed a lot and we and those are connected to transmission And I think the number is, we’ve got 84 coal sites. That could handle an AP-1000, right? So I think nothing else, but we would definitely want to fast track and what the Trump administration can do besides providing cheaper loans to the DOE is fast track the approval and siting process.

David Blackmon [00:52:29] What do you think about the Trump approach of fast-tracking the ability for developers to build plants on federal lands, you know, at federal property around the country? Some of that’s not going to work, right, because it’s not gonna be connected to enough transmission to make it go. But I mean, we have locations in Texas, in major population centers, there are five Army bases in San Antonio, for example, five military bases. In San Antonio, Texas, where you could theoretically do that. But is that an effective approach, I guess, is my question.

Paul Tice [00:53:06] Yeah, I mean, I think, you know, one of the things about the spatula power is it’s concentrated and, you know, the footprint is small, as it is such efficient energy. So I think we need to locate it, you know, near where the load is, but also where the transmission infrastructure is, because you want to minimize the delays all through the chain. I do think your point, David, around SMRs and putting them on federal land or army bases, that will eventually trigger a backlash from somebody when they realize we’re going to have these mini nukes. You know, right next door. So I’m sure locating those closer to population centers you know will lead to some delay.

David Blackmon [00:53:46] Right.

Paul Tice [00:53:47] Right? I would bank on it. So I think we should, again, the industry kind of hit this hiatus back in the late 80s. There were plans to build, you know, unit three and unit four at Vogel, you know, back then, right? And it’s the same for a lot of other nuclear sites right now, which only have two units, right?

David Blackmon [00:54:08] Yeah, Comanche Peak in Texas is one of those, yeah.

Paul Tice [00:54:11] But the problem is we need the regulators at the state level to also push it. Just like they’ve pushed renewables on us for the last 20 years, we need to get a concerted push to hopefully get the ball rolling. So I think the federal outreach also has to go to some of the state levels and maybe, you know, I mean, Georgia, South Carolina would be good candidates to build it. I mean I would say red states, but you know even blue states, you know we can’t to get our fellow citizens. Unfortunately located in blue states.

David Blackmon [00:54:44] They sometimes forget themselves is the problem.

Paul Tice [00:54:48] Yeah. So, I mean, and you’ve had happy noise made by New York State and some others about nuclear.

David Blackmon [00:54:54] And even Gavin Newsom in California, you know, is kind of moderated a little bit on the existing sites there, right, allowing them to, the one that’s still operable to continue, extended the life of it.

Paul Tice [00:55:07] Yeah, I mean, it’s going to be a much different discussion about building a new nuke in California. And I think in New York with Hope, well, I think she’s just been honestly playing Trump, because she got the Empire wind project restarted. And now she’s saying, oh, well, maybe we’ll talk about natural gas. And then she’s commissioned a study on nuclear. So that’s basically going to delay it years down the road. It’ll make it seem like she’s doing something. But we’re not building any natural gas pipelines here. And the New York State laws are kicking in at the end of this year where new construction can’t have natural gas in it, right, for private homes. And so electricity prices, as you said, they’ve been high in New York for a while and will continue to go up. And now you’re going to force people building new houses to basically heat and cook much more expensive electives.

Tammy Nemeth [00:56:02] Which will increase demand.

Paul Tice [00:56:06] Right. Right. And, you know, again, if we’re going to electrify the economy, then we shouldn’t be dependent on intermittent renewables, right, for our generation. Right. So none of this makes any sense at the end of the day. And then when you point out that renewables are raising the cost of electricity, you know, the response you get back is, no, that’s not true. And then you have these contorted arguments about why, because, you know, one of the states in the Midwest has very low cost, but nobody lives there. That apparently proves that everything you see with your eyes and your ears is not true, right? And you see it in Europe too, Tami Arena, right. I mean, every time you bring up that Germany has high electricity costs because of their bad electricity policies, it’s like, no, no no, it’s all because of natural gas, right, so the solution to that is just get rid of fossil fuels and then prices will go down.

Tammy Nemeth [00:57:00] Yeah, that’s what we hear in the U.K. Every day.

Paul Tice [00:57:04] You’re just blaming the victim, right? Yes. Basically.

Tammy Nemeth [00:57:07] So I’m wondering, Paul, would this be a case of the private equity and infrastructure companies having a project and then trying to sell it to the utilities to say, look, we think you have an issue here, we’d like to do this. Will you support it? Or is it a matter of the utilities approaching the private, equity and infrastructure companies to build these plants that they know that they need the power? Which, how will that work?

Paul Tice [00:57:36] I think it can be both. I mean, I think it could be an idea that germinates hopefully within the electric utility industry and they can be there as the buyer, right? I mean that will help any any construction commitment by a sponsor, right, if you know that the buyer is going to be there at X price, right. So I just need to make sure I can execute and preserve my margin and still sell at that price. So that be helpful but I think you know there’s nothing preventing Wall Street from basically, you know, developing this concept and then shopping around their utilities. Or, you, I think the logical thing would be to like sell the utility, sell the reactor once it’s completed, right? But there’s nothing that says that you can’t, right, because a lot of these private equity funds who are active in infrastructure, you they have fund structures that are evergreen, right? Because, you now, they realize that a 10-year private equity fund term… Probably doesn’t work when you’re investing in assets that are 75 to 100 years of operating life. So rather than forcing the fund manager to sell at a point in time for an artificial reason and maybe leave money on the table, a lot of the incumbent managers, you know, like Blackstone or GIP or Macquarie, they’ve developed these evergreen structures that can continue to hold it. So there’s nothing that’s saying that after you build it, these sponsors couldn’t also continue to Hold it. And then potentially sell it down the road. So they would have that optionality. But I think it’s a logical thing to have both of those potential tracks, right? So they’d have that flexibility. But obviously, there are a lot of counterparties that need to be involved in all these discussions, which is why I think the White House needs to kind of coordinate kind of the process and maybe kick it off.

Tammy Nemeth [00:59:30] Well, I think we’re running up to our, our stopping point here. So Paul, I flew by, oh my gosh, so many comments. Thank you to everybody who commented or had a question. Paul, thank you so much for your time in talking to us about your, your really innovative proposal for how we can get big nuclear back on the grid.

Paul Tice [00:59:54] Thanks guys, this was fun.

Irina Slav [00:59:56] Thank you. Thanks everyone. Have a lovely week.

Sponsorships are available or get your own corporate brand produced by Sandstone Media.

David Blackmon LinkedIn

The Crude Truth with Rey Trevino

Rey Trevino LinkedIn

Energy Transition Weekly Conversation

David Blackmon LinkedIn

Irina Slav LinkedIn

Armando Cavanha LinkedIn