For years, Stu Turley has sounded the alarm on the chronic underinvestment in global oil and gas exploration and production (E&P). The writing has been on the wall: without sufficient capital flowing into new discoveries and field developments, it’s only a matter of time before supply shortages hit hard, driving up prices and threatening energy security. As the host of the Energy News Beat podcast, I’ve discussed this repeatedly—pointing out how short-term thinking, investor pressures, and the rush toward renewables have left the industry vulnerable. Now, the latest data from Rystad Energy and analyses incorporating their insights, such as those from the International Energy Agency (IEA), confirm what I’ve been saying. Oil exploration is in a steep decline, investments are flattening or dropping, and we’re relying far too heavily on aging fields with high depletion rates. Let’s dive into the details, backed by recent reports, and explore what this means for the future.

The Shrinking Discovery Curve: Rystad’s Wake-Up Call

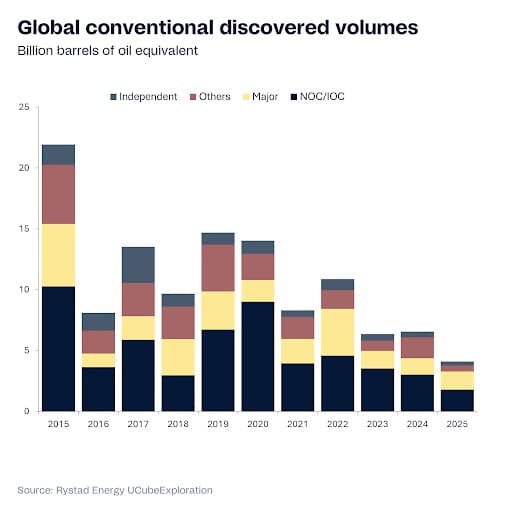

Rystad Energy’s October 2025 insight, “The Shrinking Discovery Curve: Why Exploration Still Matters,” paints a stark picture of dwindling new finds. Global conventional discovered volumes have plummeted from an average of over 20 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) per year in the early 2010s to just over 8 billion boe annually since 2020. The trend has worsened, averaging about 5.5 billion boe per year from 2023 through September 2025. This isn’t just a blip; it’s a structural shift driven by reduced exploration expenditure (expex), which has hovered between $50 billion and $60 billion annually—down from a peak of $115 billion in 2013.

These discoveries are increasingly concentrated in a handful of hotspots, like Namibia’s Orange Basin, Suriname’s deepwater plays, Guyana’s Stabroek Block (with an estimated 13 billion boe recoverable), and Brazil’s pre-salt basins. Supermajors like ExxonMobil, TotalEnergies, and Shell are leading the charge, accounting for about 22% of discovered volumes since 2015, while national oil companies (NOCs) like Petrobras dominate in their home turf. But overall, the industry is shifting away from broad exploration toward high-impact, targeted drilling in proven areas.

The implications?

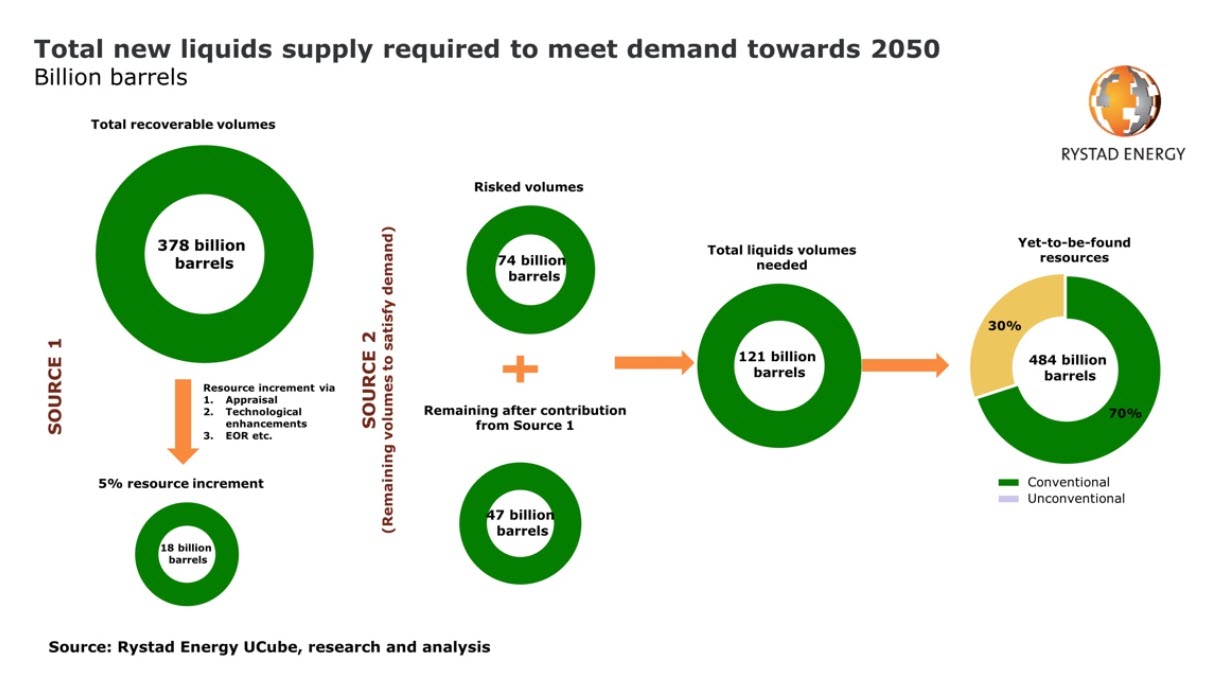

Without sustained exploration, we can’t replace reserves fast enough to offset natural declines in existing fields. Rystad warns that this could lead to supply shortages, price volatility, and challenges to the energy transition itself, as hydrocarbons will still play a role in a net-zero world. Frontier nations are offering attractive fiscal terms to lure investors, but mature producers need new finds to arrest production drops in under-explored plays like ultra-deepwater.To visualize this trend, consider the following table summarizing Rystad’s data on discovered volumes:

Investment Levels: Falling Short of What’s Needed

Turning to investments, Rystad Energy’s projections for 2025 show global oil and gas capex totaling $735 billion—a slight dip from $736 billion in 2024, marking the first decline in five years. This figure is concentrated in short-cycle, low-cost projects, with frontier exploration fading amid inflation, geopolitical risks, and energy security concerns. While natural gas demand is expected to rise through 2035, oil demand may plateau in the 2030s before a gradual decline.

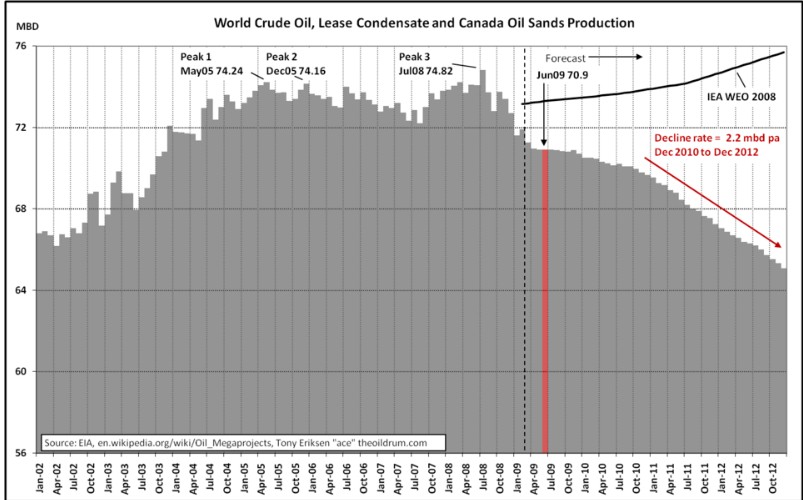

But is $735 billion enough? Analyses using Rystad’s data, including the IEA’s report on “The Implications of Oil and Gas Field Decline Rates,” suggest not. The IEA estimates that upstream investment (a subset of total capex focused on E&P) will average around $570 billion in 2025, with nearly 90% of that—about $500 billion—dedicated solely to offsetting natural declines in existing fields. Only 10% goes toward expanding supply to meet demand growth.To merely maintain current production levels through 2050, the IEA calculates that an average of $540 billion annually in upstream investment is required. At lower levels, like $150 billion, production would decline sharply, focusing only on the cheapest existing assets (under $7 per boe). Current trajectories allow for modest growth, but any drop could lead to static or falling output. Without this investment, global oil production would plummet by about 8% annually (losing over 5.5 million barrels per day, or mb/d), equivalent to the combined output of Brazil and Norway. For gas, the drop would be 9% per year (270 billion cubic meters, or bcm), matching Africa’s total production.

In short, we’re skating on thin ice. The gap between actual investments and what’s needed to counter declines is widening, echoing my long-held concerns about underfunding E&P.Reliance on Existing Fields: The High-Depletion RealityNow, let’s address the core calculation: what percentage of global oil and gas production comes from existing fields with high depletion rates? Using Rystad’s UCube database (which tracks over 30,000 assets), the IEA provides clear insights. In 2024, nearly 90% of all global oil and gas production came from fields past their production peak—meaning they’re in decline and require constant investment to sustain output.

Breaking it down:Oil: About 80% of production is from post-peak fields, which exhibit an average observed annual decline rate of 5.6% once past peak.

Gas: Around 90% comes from post-peak fields, with an average decline rate of 6.8%.

These post-peak fields are characterized by high depletion, especially in smaller offshore fields (declining up to 10.3% annually for deep offshore oil) and unconventional plays like US shale (where production can drop 35% in the first year without new drilling). Supergiant fields, mostly in the Middle East and Russia, have slower declines (2.7% for oil), but they only account for about 50% of oil and 33% of gas production. The rest relies on mature, high-depletion assets.To put this in perspective, if all investment stopped at the end of 2025, global oil output would fall to 42 mb/d by 2035 (from around 100 mb/d today), and gas to 1,600 bcm (from over 4,000 bcm). Unconventionals would suffer the most, losing over 70% by 2035. This heavy dependence on declining fields underscores the urgency: we need 45 mb/d of new oil and 2,000 bcm of new gas from conventional fields by 2050 just to offset losses—requiring annual discoveries of about 10 billion barrels of oil and 1,000 bcm of gas.

Here’s a breakdown in table form:

|

Resource

|

% from Post-Peak Fields (2024)

|

Average Observed Decline Rate

|

|---|---|---|

|

Oil

|

80%

|

5.6% per year

|

|

Gas

|

90%

|

6.8% per year

|

Charts and Visual Insights

To illustrate these trends, let’s reference key visuals from industry sources.

First, on discoveries: Rystad’s charts show a clear downward trajectory in conventional volumes.

(This chart depicts historical crude and condensate production trends, highlighting the reliance on existing supplies amid falling new discoveries.)On investments: Global upstream capex breakdowns reveal the sector’s focus.

(This illustrates market share by sector, showing upstream’s portion in the broader oil and gas capex landscape.)

For decline rates: IEA figures emphasize the accelerating natural declines.

(While specific IEA charts aren’t directly available here, the data points to steep curves, especially for unconventionals—imagine a line graph dropping 8-9% annually without capex.)

The Pricing System Will Be Changing

Also mentioned on the podcast is that the complex pricing matrices are going to be changing in 2026 and 2027. OPEC is looking to move to production and demand at the refineries to eliminate the on-water traffic and geopolitical implications. The following is from Jack Prandelli out of Switzerland on X.

🚨 OIL ONCE HAD NO PRICE 🚨

Before charts. Before futures. Before screens.For most of history, oil had no public price.

• No WTI ticker

• No futures curve

• No “market sentiment”

• Just private deals and powerWTI was not a benchmark.

It was just Texas crude flowing into… pic.twitter.com/isNHqJTuRx— Jack Prandelli (@jackprandelli) January 28, 2026

The Bottom Line: Time to Act

As mentioned above, Stu Turley has warned on Energy News Beat that the lack of investment in oil and gas E&P is setting us up for a supply crunch. Rystad’s data shows discoveries and expex at historic lows, while investments stall below levels needed to combat declines. With 80-90% of production from high-depletion fields, we can’t afford complacency. Policymakers, investors, and industry leaders must prioritize balanced energy strategies—boosting exploration while advancing transitions—to avoid volatility. The clock is ticking; let’s ensure supply keeps pace with demand before it’s too late.

So “Drill, baby, drill” sounds like a great political rally for lower prices for consumers, but the real impact on consumers could backfire if we do not invest in new exploration and the current price does not support new discoveries. There is a balance between Drill baby Drill, and Grow baby Grow. As Saudi leaders have stated, it is better to set a higher price that supports new drilling but is low enough to keep consumers satisfied.

Stay tuned to Energy News Beat for more insights. What are your thoughts? Drop a comment or join the podcast discussion.

Sources: Rystad Energy insights (October 2025), IEA report on decline rates (using Rystad UCube data), Upstream Online (November 2025).

Sources: theenergynewsbeat.substack.com,

Get your CEO on the podcast: https://sandstoneassetmgmt.com/media/

Is oil and gas right for your portfolio? https://sandstoneassetmgmt.com/invest-in-oil-and-gas/

Be the first to comment