By Michael Every of Rabobank

Yesterday was quiet due to the Martin Luther King Day holiday in the US. The trading that took place mostly saw bond yields and equities drift a little higher, neither disturbing the recent consensus that while the market arc of the universe is long, it bends towards rate cuts.

Of course, not everyone agrees.

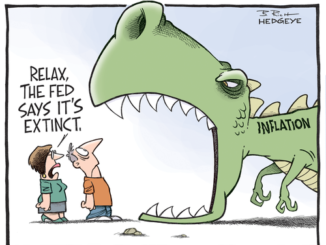

Our Fed watcher Philip Marey thinks they are on hold for all of 2023 due to a wage-price spiral; and yesterday’s Daily reiterated the “what if?” that the next rates move would have to be up if certain geopolitical slash supply side slash commodity conditions came to pass, as part of a ‘guns or butter’ reallocation of capital. At Davos, where global capital relocates to get Schwabbed, the Vice Chair of Blackrock also said rates are only going up or sideways this year, and that the market has got it wrong – which got me thinking about market expectations.

Obviously, nobody knows what the future holds – market analysis would be vastly easier if we did. Most non-analysts are not particularly interested in every analyst’s view: opinions are like ubiquitous anatomical features, and only a few draw the public’s interest – mostly the most bullish or bearish ones. Yet market pricing is seen as having explanatory power in the form of “the wisdom of crowds.”

Yes, there is wisdom in crowds. But there is madness too. Furthermore, a key problem with ‘the market says’ argument is that markets are not trying to guess the weight of a cake. They are trying to eat the cake, or to have their cake and eat it.

Talk to anyone on the equity side: isn’t it always time to buy equities? Because if not, there is less need for equity people. As a result, isn’t the ‘wisdom of that crowd’ biased?

Talk to anyone on the gold or crypto side: isn’t it always time to buy gold or crypto? Because if not, there is less need for gold and crypto people. (And indeed there are now many fewer crypto people.) As a result, isn’t the ‘wisdom of that crowd’ biased?

Talk to anyone on the traditionally staid bond side: isn’t it always shortly time to buy bonds too? Because higher yields destroy a financialised, highly indebted economy, what goes up must always come down. Because if not, there is less need for bond people telling you that. As a result, isn’t the ‘wisdom of that crowd’ biased?

Talk to anyone in economics: doesn’t inflation always return to the central bank target of 2%? That’s the thought process as well as the function of their DSGE models. Because while this may not mean less need for economics people, it does mean more need for a different kind of economist – one who understands political economy, or logistics, etc. Indeed, saying inflation doesn’t come down means admitting the whole economic paradigm has changed. And what do you do when you only have a hammer and a screw, or a rawl plug, not a nail? As a result, isn’t the ‘wisdom of that crowd’ biased?

The above points are linked: because ‘inflation always goes back to 2%’, ‘bond yields always come down’, and so equities always go up’. Hence we need lots of traditional economists, bond people, and equity people. How convenient – and biased.

The gold argument is the mirror-universe, bearded-Spock inverse: ‘inflation never comes down, and bond yields either rise a lot or cannot rise a lot, because fiat’. Crypto is the same plus monkeys in sunglasses. Conveniently, this means the need for lots of gold and crypto people. And another form of bias.

In short, asking markets about the inflation and rates outlook, when so few in markets are truly neutral, is like asking very small children what they think is going to be for dinner: it’s always going to be chocolate and fries. That’s what they actually think, because that’s what they want it to be.

So, is it worth listening to “the wisdom of crowds”? Yes, because you get trampled if not. And no, because no matter how much you want chocolate and fries for dinner when you are 3, the odds of your parent putting that on the table every day are fairly low.

Indeed, although central banks are refusing to fully admit that their models are wrong, and that the entire global political-economy structure is changing, because they are sticking to 2% assumed targets longer term, they are making clear that in order to get to that 2% level they are prepared to see every other variable move: unemployment higher; growth lower; and asset prices lower. That is the equivalent of a plate of greens for a 3-year old. It’s good for them in the long run, but entirely unpalatable compared to chocolate and fries.

The current market rally is the equivalent of a young child repeating “Chocolate and fries!” in the belief that the parent will buckle. It will be followed by a market tantrum when it realizes that it is dreaded greens after all. Their hope then is then that parents’ delicate eardrums/central banks’ asset bias will see them relent, and proffer chocolate and/or fries. Which, to be fair, some childless cynics have as the basis for their calls for lower bond yields and higher equities, etc., rather than any real belief in that view.

Except, in a nod to gold and crypto-nites, the geopolitical backdrop for such policy pivots really is changing. We do have hammers and screws and rawl plugs, not nails. If you think central banks can ‘just’ return to 2019 via low, low rates, QE, and high, high asset prices, you are also selling yourself a narrative like yummy chocolate and fries. Doesn’t it suit your book to be doing so? If not, then, yes, give it more credence.

Let’s see what a rates pivot would do to parenting/central bank credibility; to commodity prices; to supply chains; and so to inflation – unless we have a real deflation overshot into a biting global recession. Yet in that case we also know that any reflation attempt will be behind protectionist walls, as long projected here, and now bewailed by The Economist, et al. as being the real junk food.

The issue is what happens next if it isn’t chocolate and fries: and I don’t think the average market analyst, or the wisdom of crowds, or global capital in Davos has any real idea – or at least not an idea that also works for them. So, what’s for dinner tonight? Volatility. It’s just still in the oven.

By the way, today’s key Chinese data were another example of chocolate and fries. The market didn’t have to demand good outcomes there: it was given to them directly. No sooner had Covid Zero been reversed than backwards data into December came out as amazingly good too. As a result, Q4 GDP was a huge beat. It was all a sweet, greasy hit of junk that doesn’t sit easily in the stomach.

December industrial production soared 1.3% y-oy vs. 0.1% expected; retail sales were -1.8% y-o-y vs. -9.0% expected(!); fixed asset investment was 5.1% y-o-y year-to-date (y-t-d) vs. an expected 5.0%; property investment was -10.0% y-o-y y-t-d vs. -10.5% consensus; and unemployment declined from 5.7% to 5.5% rather than rising to 5.8%. Q4 GDP therefore leaped 2.9% y-o-y, not 1.6% as foreseen, and was flat q-o-q, not -1.1%, marking 2022 with 3% GDP growth, not 2.7%. If you read the small print of the release carefully, China also won the FIFA 2022 World Cup.

Loading…