This is the Dec. 29, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Another year gone by. Another 365 days of drought, fire, flood and heat. With more to come in the New Year.

You’ve heard it all before; I won’t ask you to relive every blow struck by the climate crisis over the last 12 months. But there are lessons to learn, and they’re not all scary. We’ve got plenty of reasons to worry — and also cause for hope.

Here are my top 10 climate takeaways from 2022, with a focus on California and the American West.

1. Doom is not inevitable

Before Joe Manchin III’s sudden reversal in July, I thought there was no chance Congress would pass a major climate bill this year, ahead of a November election that would probably return the House and Senate to Republican control. The West Virginia senator had previously nixed several climate deals, using his leverage as the most conservative Democrat in a Senate split 50-50.

Then Manchin changed course, and suddenly the U.S. had its most expansive climate legislation ever. The Inflation Reduction Act devoted nearly $370 billion to climate and clean energy initiatives, including support for solar panels and wind turbines.

The bill’s passage was a reminder that as bad as the climate outlook is, we’re not irredeemably doomed. Yes, some temperature increases are locked in due to carbon we’ve already spewed into the atmosphere. But we can still stop the damage from getting a lot worse. The politics of change aren’t hopeless.

That said…

2. Progress isn’t inevitable, either

Despite support from Congress, the renewable energy industry faced dramatic headwinds in 2022. Supply-chain backups, power-grid backlogs and other logistical challenges led to higher prices and lengthy delays for solar, wind and battery projects.

Long term, clean power prices are likely to keep falling, for the same reasons they’ve declined so dramatically over the last decade — economies of scale, government support and more. But scientists say we need to cut carbon emissions nearly in half by 2030 — just seven years away. And at least for now, those emissions continue to rise. We’re running low on time.

The Inflation Reduction Act should help. But it’s far from clear whether political leaders, and U.S. voters, will continue to prioritize renewable energy. Democrats kept control of the Senate but lost the House, after a campaign in which they barely talked about climate. Global warming was similarly not a focus in the Los Angeles mayoral election. Californians rejected a ballot measure that would have taxed the wealthy to generate tens of billions of dollars to build electric car chargers.

Speaking of which…

3. The oil industry is far from dead

All those clean energy investments in the Inflation Reduction Act? Manchin agreed to them only because the bill also requires continued oil and gas leasing on public lands and waters, which President Biden had promised to end. Climate analysts say the bill should do far more good than harm despite that compromise. But the leasing provisions are a sign of the oil industry’s continued political strength.

At least in California, fossil fuel companies aren’t as powerful as they used to be, or lawmakers wouldn’t have been able to ban new drilling within 3,200 feet of homes and schools. That bill, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, had failed for years.

But it might not last. Oil and gas companies appear poised to place a measure on the 2024 ballot that would overturn the drilling ban. Even if voters ultimately reject the ballot measure, the restrictions on drilling would be delayed for two years.

It’s not just fossil fuel companies looking out for the bottom line…

4. Electric utilities will do what is best for them

Utility companies can be some of the biggest beneficiaries of climate action, and thus some of its most powerful supporters. The campaign by climate activists to “electrify everything” — including cars, trucks, home heating systems and kitchen stoves — would create loads of business for electric utilities. There’s a reason they went to bat for the Inflation Reduction Act.

But when it comes to clean energy technologies and business models that threaten their monopolies, electric companies often find themselves at odds with climate activists. In the Golden State, regulators slashed rooftop solar incentives this month after a successful years-long campaign by Southern California Edison, Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric.

In the Southeast, meanwhile, major utilities employed a consulting firm that funneled money to news sites and paid an ABC News producer to attack political candidates not sufficiently sympathetic to those utilities — at times in an effort to undermine rooftop solar, as NPR’s David Folkenflik and Floodlight’s Mario Ariza and Miranda Green report in a startling new investigation.

5. Aridification is now the West’s main water problem

Yes, California and other Western states are still mired in drought. But even if we get a few years of normal rain and snow, our water problems won’t be over. And that’s because of aridification. As my colleague Ian James explains, the West is experiencing a long-term drying trend due to global warming. The last two decades have been the driest period in at least 1,200 years.

So prepare to see photos of depleted reservoirs for the rest of your life. Make water conservation part of your daily routine. And if you live in California’s Central Valley or another farming region, get ready for some tough choices. Agriculture uses about 80% of the water in the Colorado River Basin. Saving the Colorado and other rivers will require farmers to use a lot less.

Aridification is also diminishing hydroelectricity production at dams. Which brings us to…

6. Climate change is making it harder to solve climate change

As the planet gets hotter, it’s getting harder to keep the lights on — especially on hot summer evenings. Partly, that’s because people are using more air conditioning, resulting in higher electricity demand. Partly, it’s because of the aforementioned loss of hydropower. And partly, it’s because we’re increasingly dependent on solar panels, which stop producing energy after dark.

Those forces created chaos on the California power grid in early September. For 10 straight days, state officials begged homes and businesses to use less electricity in the evenings. For the second summer in a row, we barely avoided rolling blackouts.

Power companies are building lithium-ion batteries as fast as possible to store solar power for after dark. But as much as those storage facilities are beginning to help, there aren’t enough of them yet to ensure the lights stay on. Which explains why Newsom signed a bill this year aimed at extending the life of four coastal gas plants — gas plants that worsen the climate crisis, but which can be fired up relatively quickly and supply power after the sun goes down.

It’s not just California struggling to balance supply and demand as climate change screws around with weather patterns, solar and wind power replace fossil fuels and U.S. energy infrastructure gets older. Just this week, parts of the country experienced rolling blackouts as a deadly winter storm drove up demand for home heating and froze natural gas wells and pipelines.

Despite those trends, though…

7. Coal power is still dying

I wrote at the beginning of 2022 about the last coal plants clinging to life in the American West. I counted fewer than 10 plants without planned retirement dates as lower-cost renewables and natural gas outcompeted the dirtiest fossil fuel.

The outlook for coal has only gotten bleaker since then. Two Montana laws designed to save the massive Colstrip coal plant were declared unconstitutional by a judge. A cryptocurrency miner cut ties with a smaller Montana coal plant that it had been helping keep afloat. The New Mexico city of Farmington gave up on saving the San Juan coal plant, which shut down in September.

Utah and Wyoming continue to be strongholds for coal power. But even there, utility companies owned by investors including Warren Buffett are making long-term plans to transition to cleaner energy.

And not just solar and wind…

8. Keep an eye on hydrogen — and nuclear

There’s growing excitement in the energy world for green hydrogen as a kind of jack-of-all-trades, a power source that can do things solar panels, wind turbines and batteries just aren’t good at. Created by using renewable energy to split water molecules, green hydrogen is a clean-burning fuel that can potentially be used in power plants, home appliances and elsewhere.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power spent 2022 beginning construction of a green hydrogen plant in Utah that will replace the city’s coal-fired generators there — a project that was novel when it was first proposed in 2019, but which is now seen as a model by utilities across the country. Southern California Gas, meanwhile, proposed a multibillion-dollar pipeline known as Angeles Link that would bring green hydrogen to power plants and other industries in the L.A. Basin.

But green hydrogen is no sure bet. And some activists worry companies such as SoCalGas will use the fuel as an excuse to slow the transition to electric cars and electric appliances, which they see as more feasible, less dangerous climate solutions.

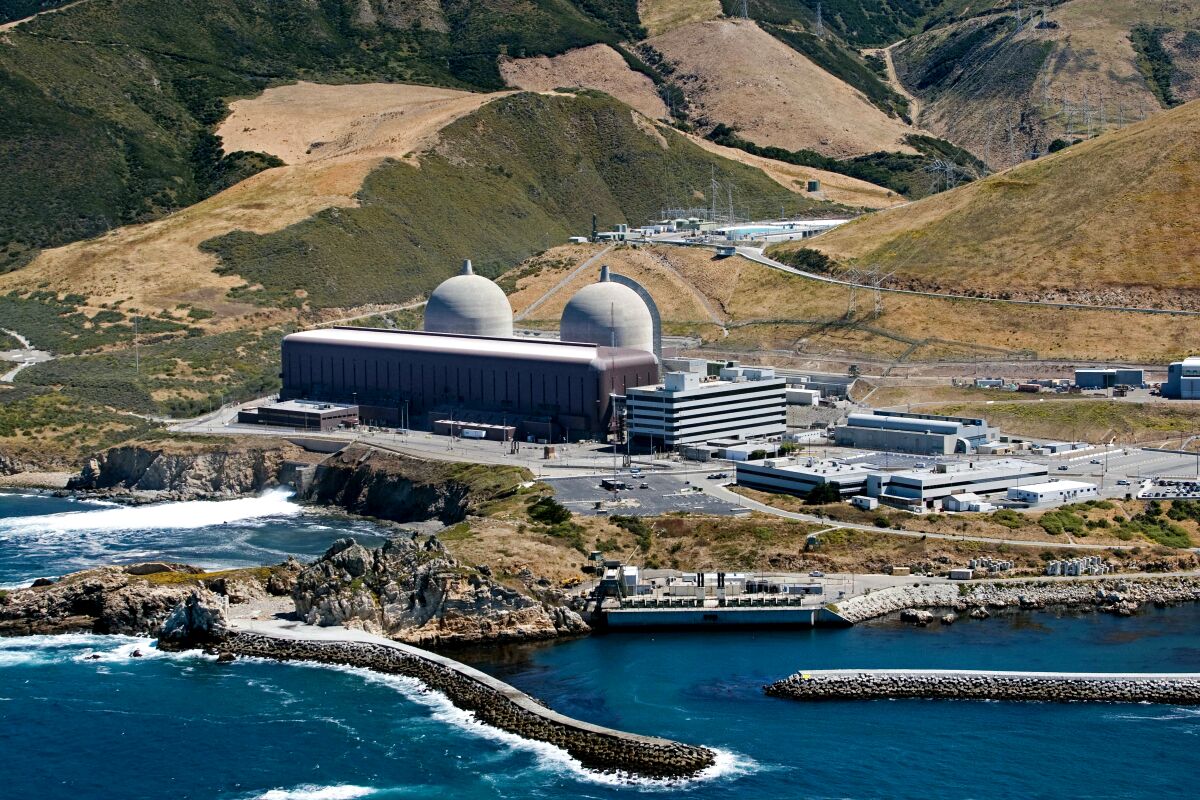

Other companies see nuclear power as a potential climate savior, although some early-stage efforts to build smaller, less expensive reactors have faced delays and rising costs. Efforts to stop existing nuclear power plants from shutting down are likely to yield greater climate dividends, at least in the short term. Newsom and Biden joined forces this year in an attempt to extend the life of PG&E’s Diablo Canyon nuclear plant — California’s single largest electricity source — from 2025 through at least 2030.

As always, nuclear power is extremely controversial. But it may not be the biggest climate battle on the horizon…

9. Land-use conflicts are on the rise

As energy companies seek to build thousands of solar, wind and battery facilities across the country, more of those projects are facing public pushback. Whether that pushback comes from small-town residents who don’t want to look at wind turbines, farmers who don’t want to see panels replace agricultural land, or conservationists who don’t want to see wildlife habitat destroyed, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to build renewable energy infrastructure without first overcoming local opposition.

It’s a trend I’m documenting through the Repowering the West reporting project, and I’m convinced it will be one of the defining climate stories of the coming decades. Tensions are already high. Renewable energy developers say more land should be opened to solar and wind farms. Conservation activists say it’s possible to build enough clean energy while protecting the most important wildlife habitat and farmland. And some local governments have banned solar and wind farms from large areas.

Keeping global warming to manageable levels will depend on California — and the rest of the nation — finding a way to navigate those tensions, without creating political blowback that derails the clean energy transition. It won’t be easy.

On the bright side…

10. Not every year will be hell

California had some nasty wildfires over the last 12 months. But 2022 wasn’t nearly as bad as the two years that preceded it, in terms of acres burned. About 360,000 acres went up in smoke, compared to 2.5 million in 2021 and 4.3 million in 2020.

Yes, 2020 and 2021 were record fire years. And yes, there was plenty of destruction this year, including nine deaths, compared to three last year. But 2022 could have been a lot worse. The Times’ Alex Wigglesworth wrote about what went right, including well-timed rainstorms and government investment in wildfire resilience projects such as forest thinning and prescribed burns.

Not every year will be worse than the last. It’s a small blessing, maybe. But let’s take our gratitude where we can get it.

Here at the Los Angeles Times, we’ll do our best to keep bringing you climate, energy and environment stories that hopefully help solve these problems. If our work was meaningful to you this year, please consider subscribing to help us keep doing it.

Source: Latimes.com