Contributions rose by 5.6%, but benefit payments rose by 8.5%. The Trust Fund paid for the deficit, so its balance declined further, to $2.6 trillion.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

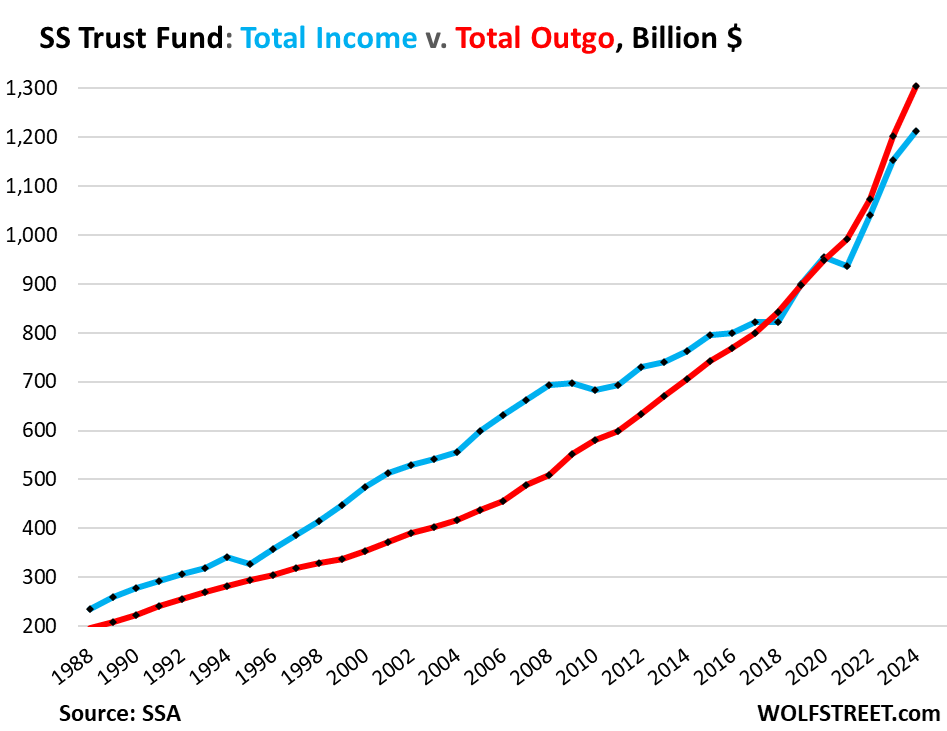

Total income of the Social Security Trust Fund – technically “Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund” – rose by $61 billion (+5.3%) in the fiscal year ended September 30, to a record $1.21 trillion, according to the Social Security Administration (blue line in the chart below).

By category of income:

- Contributions: +$58 billion (+5.6%), to $1.10 trillion due to employment growth and higher wages.

- Interest income from the securities in the Trust Fund: roughly unchanged at $63 billion.

- Taxation of benefits: +$3 billion to $53 billion.

But the outgo rose faster than income. Total outgo rose by $102 billion, or by 8.5%, to a record $1.30 trillion (red line).

By category of outgo:

- Benefit payments: +$102 billion (+8.5%), to $1.29 trillion; more retirees drawing benefits; and COLAs of 8.7% for October, November, and December 2023, and 3.2% this year.

- Administrative expenses: +$500 million to $4.8 billion. They’re relatively small: 0.17% of the Trust Fund balance, and 0.40% of total income.

- Transfer to Railroad Retirement Program: +$300 million to $5.9 billion

When the total income (blue) was above the total outgo (red), the Trust Fund ran a surplus and thereby accumulated assets. When the red line rose above the blue line, the Trust Fund ran a deficit and its assets shrank.

The low 2.5% COLA for the 2025 calendar year will slow the growth of the outgo from that direction, but increasing retirements of boomers will cause the outgo to increase further.

The Social Security Trust Fund.

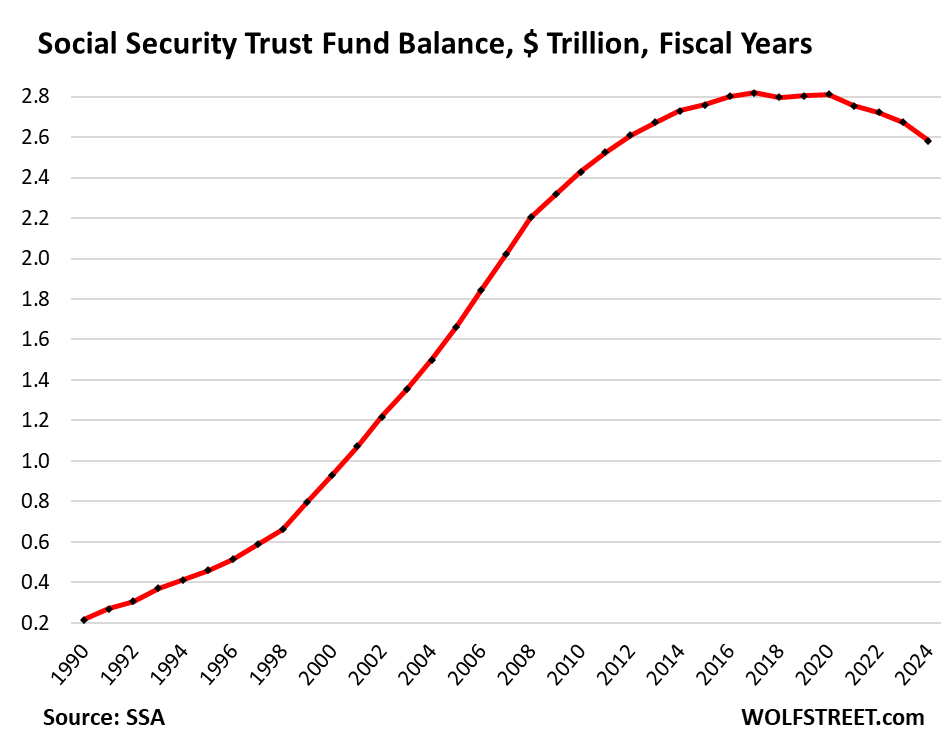

The deficit in the fiscal year was $91.5 billion, the biggest deficit yet, and the fourth year in a row of deficits.

Over the past 35 years, 30 years had surpluses, totaling $2.6 trillion, which accumulated in the Trust Fund. Five years had deficits (2018, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024), totaling $225 billion.

The shortage between income and outgo is paid out of the Trust Fund, and in the fiscal year, the Trust Fund balance declined by the amount of the deficit, by $91.5 billion, or by 3.4%, to $2.58 trillion.

These figures to not include the Disability Insurance Trust Fund, which by law is a separate entity from the OASI Trust Fund, and is not part of this discussion here.

How the Trust Fund invested the $2.58 trillion.

At the end of the fiscal year, the Trust Fund held $2.39 trillion in interest-bearing special-issue Treasury securities and $197 billion in short-term cash-management securities (“certificates of indebtedness”).

These securities are not traded in the secondary market, and are not subject to the whims of the secondary market, similar to the Treasury I bonds and EE savings bonds that retail investors hold in their accounts at TreasuryDirect.

So the value of these holdings – like the value of investors’ accounts at TreasuryDirect – doesn’t fluctuate with the trading prices in the secondary market. The Trust Fund holds Treasury securities until they mature and then gets paid face value for them. Day-to-day price fluctuations are irrelevant for the Trust Fund.

Investing in Treasury securities when they’re issued and holding them until they mature is a low-risk conservative strategy.

This strategy allows the SSA to operate the system with ultra-low administrative expenses, amounting to just 0.17% of the assets under management.

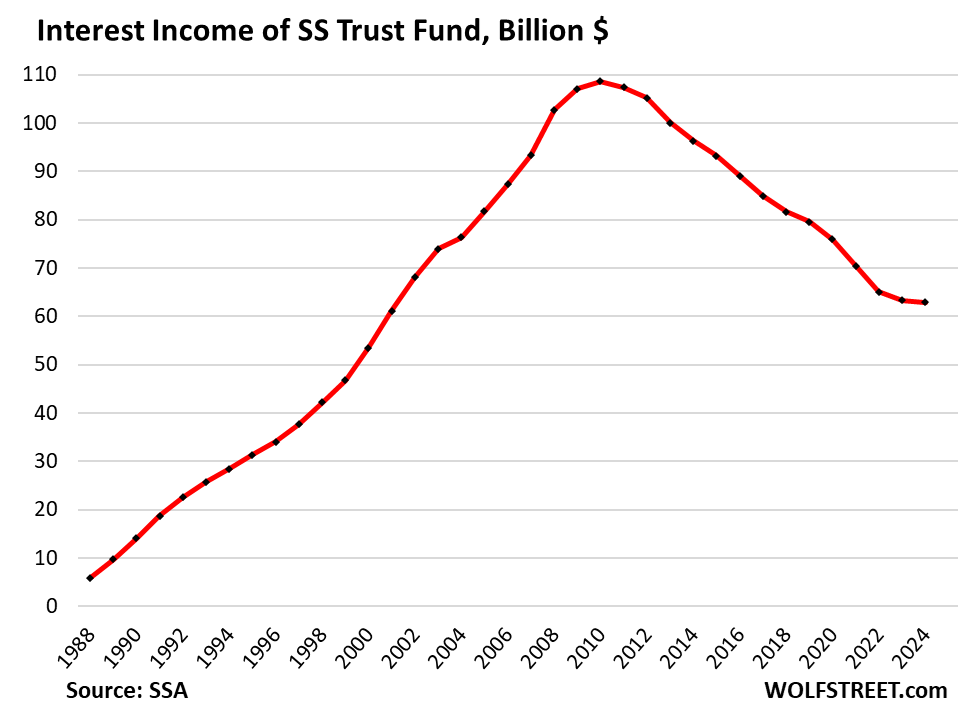

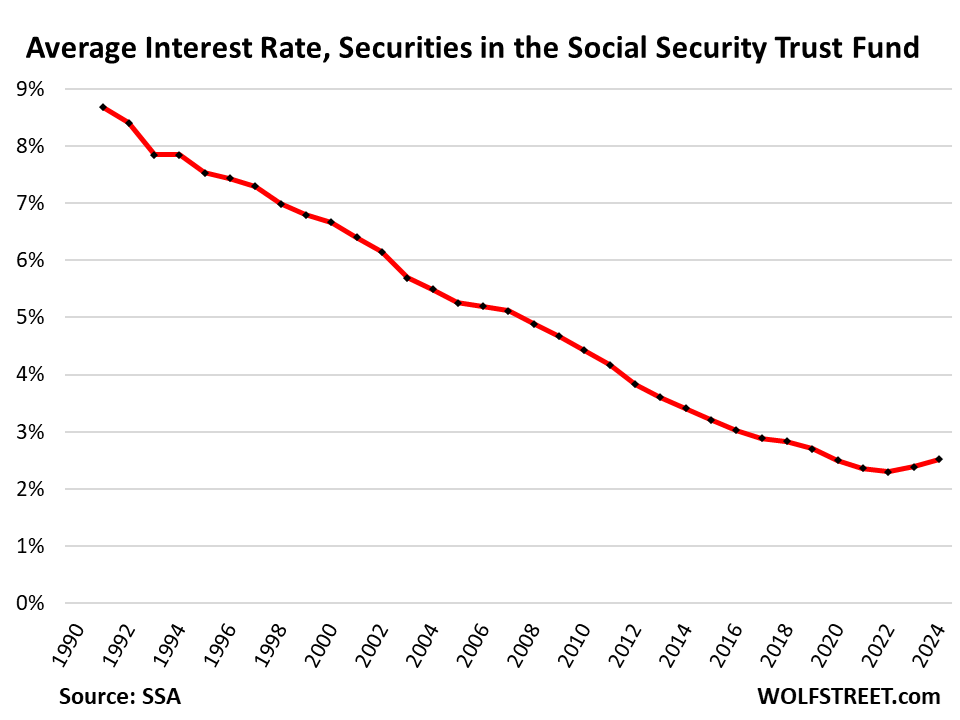

Fed’s interest rate repression contributed to the deficit.

The Trust Fund earned $63 billion in interest on its Treasury securities in the fiscal year, down by 42% from the peak in 2010, though the Trust Fund balance was a little lower than today.

When the higher-interest-rate securities from before the Financial Crisis matured in 2008 and later, they were replaced with much lower-interest-rate securities as a result of the Fed’s interest rate repression, including QE, which pushed down longer-term interest rates until the 10-year yield finally dropped below 1% in mid-2020.

And the interest income of the Trust Fund – along with the interest income of all yield investors, including savers – took a massive hit.

For example, this fiscal year: If the Trust Fund had earned an average 4.5% on its balance of $2.39 trillion of Treasury securities, it would have earned $107 billion in interest income, instead of $63 billion, and the Fund’s deficit would have been $47 billion, instead of $91.5 billion. Last year, it would have had a surplus!

Now, the maturing low-interest rate securities are replaced with higher-interest rate securities, which is slowly pushing up the average interest rate earned by the Trust Fund.

The average interest rate the Trust Fund earned rose to 2.52% in the fiscal year, from 2.39% a year earlier, and from the low of 2.30% in 2022.

Going forward, the average interest rate will continue to rise as those very-low interest-rate securities, including those issued in 2020, are replaced with higher interest-rate securities. For example, the 10-year yield has risen to 4.3%, from below 1% in mid-2020.

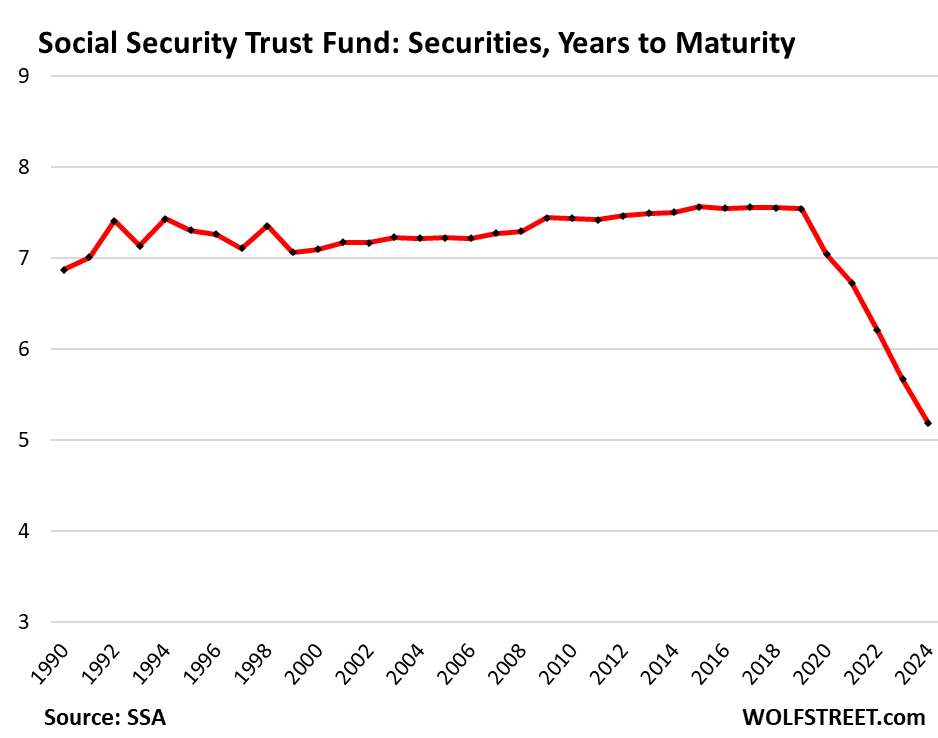

Shifting to shorter-term securities.

The average number of years to maturity used to be around 7 to 7.5 years. But in 2020 it began to drop, likely a strategic decision by the SSA to not load up on the near-0% longer-term securities issued at the time.

In the fiscal year, the average years to maturity declined to 5.19 years, the shortest on record. And the current crop of higher-yielding securities is going to make its way into the Fund a little more quickly.

Tweaking the plan is necessary.

The deficit of $91 billion this year is not large for a $29 trillion economy. If no changes are made to the plan, the Trust Fund will be depleted in about 10 years, and at that out-of-money point, without adjustments till then, either the benefits would need to be trimmed by some percentage to match income on an annual basis, or the general budget would be used to make up the difference. That’s the worst-case scenario, if Congress doesn’t get its act together.

Various proposals have been floated in Congress over the years to tweak the system, but they have gone nowhere. Generally, each proposal tweaks the system in several ways, and each tweak could be relatively small, but combined and over time, it’ll get there. It was done before, and somehow it ended up not being the end of the world. And it can be done again.

We give you energy news and help invest in energy projects too, click here to learn more

Crude Oil, LNG, Jet Fuel price quote

ENB Top News

ENB

Energy Dashboard

ENB Podcast

ENB Substack

![]()