Britons tend to downplay the empire’s slave-trading history. But its links to Virginia tobacco are all over the landscape.

The Irish Sea churns against St. Bees Head. This is northern England’s most westerly tip, in a part of Cumbria once known as Cumberland. Here, giant cliffs face the sea; beyond it lies the Atlantic and North America. Today this is an established heritage coast, its cliffs crowded with seabirds and rare species; the sea below is a marine conservation zone.

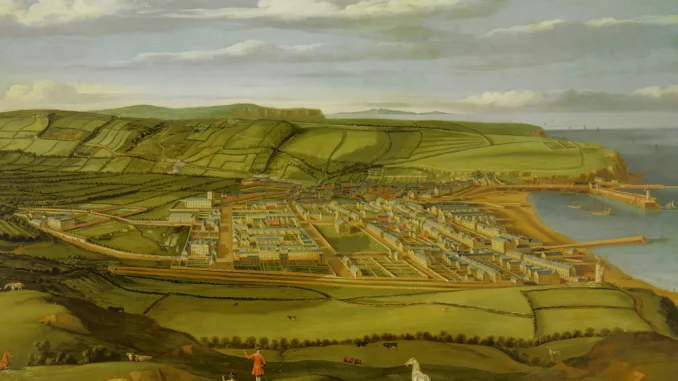

The coast is part of a gigantic coalfield, and coal seams run for 14 miles from St. Bees north to the coastal town of Maryport. Between them lies the Georgian town of Whitehaven. Once a huddle of fisherman’s cabins and thatched cottages, Whitehaven became a major port with sweeping streets and generous mansions belonging to wealthy merchants. Nowadays, Whitehaven styles itself as the place where the Lake District meets the sea. The town’s gentility has faded, and the peeling stuccoed houses rub shoulders with boarded-up shops.

Remote as Whitehaven was from Britain’s urban centers, the isolated coal town nonetheless became the nation’s second-largest tobacco importer and its fifth-biggest slave-trading port. From the 1680s, Whitehaven’s townspeople became tobacco traders, plantation owners, and slavers. In the fullness of time, these colonial figures became magistrates, customs officials, industrialists, and politicians. They climbed the social ranks, married into wealthy families, and gained power and political influence. Transatlantic profits were reinvested in local infrastructure, much of which still stands today.

The British tend to associate the nation’s slavery past with faraway plantations in places such as Louisiana or well-known slave-trading ports such as Liverpool. Yet Britain’s country estates, fields, and hamlets were everywhere altered by imperial wealth of all kinds, whether from the West Indies, America’s southern states, or India. Landownership, for instance, is among empire’s most significant legacies in rural Britain: In the 18th and 19th centuries, colonial profits intensified the process of enclosure, accounting for significant land sales whereby landless locals lost their right of access to common land. Many a British hedgerow was laid with colonial wealth, and many a quintessentially English-looking village church was built with the proceeds of empire. The Whitehaven coast is a prime example of these hidden histories of empire, since its tobacco and slavery history forever altered its built heritage.

A painting depicts an English Navy officer kidnapping an enslaved woman on Barbados Pier, from John Mitford’s “Adventures of Johnny Newcome in the Navy,” London, 1819. Charles Williams illustrationFlorilegius/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

One sunny November day in 2022, I took a walk along the coast, beginning seven miles south of Whitehaven at the village of St. Bees, with Peter Kalu, a writer from Manchester. Peter knows the place well. A decade before our walk, he’d visited the area to read some papers about Barbados in Whitehaven’s local archive, where he’d stumbled across a copy of a 1770s diary about plantation life in Barbados and, for the first time in his life, encountered the words and thoughts of a slave owner. His response was to start writing historical fiction about British slavery. This was no easy challenge, for his personal relationship to colonial history is complicated: His mother is Danish, his father Nigerian. “The invader and the looted inhabitant,” he told me with a wry smile, though there’s no doubt where his sympathies lie.

As a writing mentor and editor, Peter has had a galvanizing effect on the region’s literary culture. History, race, and class are prominent themes in his writing, which spans poetry, fiction, folktales, plays, songs, and film scripts. His crime novel Yard Dogs, for instance, references Manchester’s cotton history and the origins of its wealth in the slave trade and exploited local labor.

The morning of our walk was bright. As we ambled along the beach toward the cliffs, Peter told me about a poem he’d recently written and performed for some schoolchildren. It was about a boomerang, reversing in mid-flight and coming back to smack you in the face. The boomerang was a metaphor for colonialism, which returns with its consequences (looted museum objects, controversial statues, repressed histories). The metaphor well describes his first encounter with the words of that 18th-century enslaver in Whitehaven’s archives. “There I was,” he said, “the son of a Nigerian father, hit between the eyes by an account of plantation violence.”

The diary belonged to a man called Joseph Senhouse, who was born in 1741 in Maryport on the Whitehaven coast, where the Senhouses dominated trade and held sway as landowners, in customs, and as developers and manufacturers. Joseph’s older brother William was active in the colonial trade. William became surveyor general of customs in Barbados in the 1770s and acquired a sugar plantation. Following in his footsteps, Joseph became collector of customs on the West Indian island of Dominica, where he owned a coffee plantation.

Sitting in the Whitehaven archives, Peter was stunned by Joseph Senhouse’s account of his visit to his brother’s Barbadian estates. “What affected me most,” he told me, “was the thingification of Black people.” What Peter meant was that, even when detailing upsetting incidents, Joseph Senhouse appeared to find it all a curious good yarn. He describes the suicide of an enslaved man who, threatened with punishment for absenteeism, jumped into a vat of boiling cane sugar.

Before the area’s leading families entered the transatlantic trade, they made their fortune through coal exports. In the early 17th century, Whitehaven was the territory of the Lowther family. Coal formed the bedrock of their wealth, as they monopolized its extraction, transportation, and sale to Ireland.

During those early coal years, a trade was developing far away in colonial Virginia that would soon transform Whitehaven. English colonists were cultivating a new strain of tobacco to suit European tastes, and tobacco soon drove the colony’s economic development. By the 1620s, plantations were being cleared, and port towns and warehouses springing up. So valuable did tobacco become that its leaves were known as “brown gold.” As the century wore on and plantations became more established, the rising demand for labor saw the increased transportation of enslaved laborers to Virginia.

Meanwhile, the Lowther coal trade was expanding. This burgeoning industry turned Whitehaven from a fishing village into a major coaling port and a planned town designed by John Lowther, the heir to the family’s coalfields and estate. Alongside his wealth, Lowther obtained power. In 1664, he became a member of Parliament for Cumberland, a seat he held for three decades. A member of the Admiralty, Sir John (he had also picked up a knighthood) knew that colonial commerce was everywhere. His head of collieries was a man named John Gale, who owned a Maryland tobacco plantation and fed Lowther information about Whitehaven’s tobacco trade. The Gales were helped into colonial trade by the Whitehaven-born slaver Isaac Milner, who was a key networker in London’s slavery business.

Alive to potential colonial profits, Sir John invested in the South Sea and East India Companies and in the 1660s explored the possibility of investing in the Royal African Company, set up by the newly reestablished Stuart monarchy and London merchants. Refounded in 1672 after heavy initial losses, the company charter lists Lowther as a member. The charter permitted the company to establish forts and factories on the West African coast, and—as with the East India Company—to maintain a standing army. The company was also handed a monopoly on the increasingly lucrative trade in trafficking people from West Africa. Colonial investments would form a significant portion of the Lowther family’s wealth across the generations.

By this point, other regional families were involved in colonial affairs, including the Senhouses, with their links to Barbados and Dominica, and the Curwens, connected to the East India Company, who presided over nearby Workington. Through the expanding port of Whitehaven, local people became well informed about colonial affairs in Virginia, Maryland, India, and Africa—and the opportunities that presented themselves in these far-flung places.

Residential properties in Whitehaven on Dec. 8, 2022. Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images

A few miles into our walk, as Peter and I headed north along the clifftops toward Whitehaven, we returned to the topic of writing. Being a Black writer in Britain, Peter reflected, is like being “a stranger at the gates.” It’s not just that Britain, like many other former empires, has tended to avoid, or even deny, the basic historical facts of colonialism. Rather, he continued, there is “a racial empathy gap,” in particular with slavery history. Writers like Toni Morrison have, he explained, said more or less the same. Peter described the problem he faced in his historical fiction: of somehow representing black-skinned people to groups of White readers who might well see themselves as “universal,” he said, quoting Morrison directly now, or “race-free.”

Slavery, of course, was central to the tobacco trade. And tobacco made Whitehaven rich. In the 1680s, a 94-ton ship called the Resolution entered Whitehaven port loaded with tobacco packed into large barrels, or hogsheads, marking the beginning of the town’s colonial trade. Tobacco warehouses were soon built at Whitehaven port to weigh, inspect, and store the hogsheads. The ships kept coming. In 1693, customs officers logged 10 vessels from Virginia; 10 more arrived the following year, rising to 20 in 1697. In 1699, a clay pipe-house was opened, and a tobacco processing plant began work in 1718.

By the 1740s, Whitehaven was second only to London for tobacco imports: “tobacco,” opined one local official, was “the very life and soul of Whitehaven.” The heyday of Whitehaven’s tobacco trade opened up opportunities, and not only for local merchants. Many worked on ships, became apprenticed clerks, or found positions in booming businesses such as iron forges or fisheries to supply food to the growing population.

By the early 18th century, as it became a hub of colonial trade, the town made its almost inevitable entry into the slave trade. Local merchants found investors for slaving ships. The Royal African Company maintained its monopoly on slave-trading, but there were many independent merchants and sea captains who, setting themselves up in provincial ports, wanted to get in on the lucrative slave trade. In Whitehaven, a temporary decline in tobacco trade coincided with this increase in slave-trading.

The Whitehaven slave trade developed along its existing trade routes for coal and tobacco. In 1716, the Whitehaven Galley left the harbor loaded with coal, which was sold in Dublin. There, the ship was filled with goods such as Irish linen, salt beef, candles made from Irish tallow, and other provisions. From Dublin the ship sailed to West Africa, where its goods were sold or traded. Crossing the Atlantic from West Africa with its cargo of enslaved people, Whitehaven Galley put in at Montserrat, Jamaica, and Honduras, where it loaded up for the return journey with ivory, logwood, and anatta dye. Likewise in 1759, the locally built Betty cleared port, sailing to the Sierra Leone estuary; later, it disembarked 210 enslaved people in Charleston, where many Whitehaven tobacco merchants had connections.

Whitehaven’s slave-trading business lasted some 60 years, petering out by the late 1760s, decades before the abolition of slavery in Britain. It’s thought that there were insufficient quality goods made locally to trade in West Africa (hence the stopovers for Irish linen and tallow), while merchants were ultimately dissuaded from a trade that gave uncertain financial returns. In other words, there was nothing particularly moral about Whitehaven’s turn away from the slave trade: The reasons were purely economic. Although many locals claim that Whitehaven had a minor slave-trading history, the town was once Britain’s fifth-largest slave-trading port. Its merchants trafficked more than 5,739 people and caused at least 906 deaths on transatlantic voyages.

Transatlantic traders pumped money into many local businesses, including ironworks and ropemaking. They invested heavily in shipbuilding, too: Transatlantic vessels and slaving ships

were built and repaired just north of Whitehaven. Sail-makers operated from the town, and the Lowther family leased premises to shipwrights. Local cloth traders expanded across Cumbria to supply the colonial trade, especially along Africa’s west coast.

Just as Whitehaven’s harbor expanded, so, too, did the town. In the lifetimes of Sir John Lowther and his son James, the local population had increased from 250 to well over 3,000. This growing population needed infrastructure. The building of houses and factories, and the constant upgrading of the harbor, provided jobs, as did the local brickworks, owned by Walter Lutwidge, an Irish-born slaver, tobacco merchant, and lighthouse-builder.

With the footpath now bringing us inches from the cliff edge, we walked in single file. We crossed a bracken-covered hill, and the path broadened into a track past old mineworks. As the coastline descended to sea level, we arrived at Whitehaven harbor. In the distance, we could see the marina and the climb to Lowther Castle, a three-story castellated building. The harbor itself was eerie. A white lighthouse at its entrance was dwarfed by the seaweed-covered harbor walls.

Beside the harbor was Whitehaven’s Beacon Museum. We popped in to see a large goblet that commemorates a slave ship called the King George. It is engraved with the Royal Coat of Arms and depicts a sailing ship with the words: “Success to the African Trade of Whitehaven.”

We wandered into the town. Today, Whitehaven remains the most complete Georgian town in Europe, and 268 of its buildings appear on Historic England’s list of the most important historic constructions. The streets are wide, the squares generous, the houses evenly designed. Through it runs Lowther Street, arrow-straight from Lowther Castle to the port, a statement of the family’s dominance.

We passed the Rum Story Museum, but having previously looked in, I didn’t have the heart to suggest we go inside. The museum does not yet close the “racial empathy gap.” Although it acknowledges the connection between rum production and human enslavement, the museum primarily celebrates the Jefferson family, which set up Whitehaven’s rum cellars in the early 19th century by trading with Virginia and the West Indies. Today you can enter the old, barrel-filled cellars of their base at 27 Lowther Street to view rooms with displays of tropical forests, sailing ships, rum bottles, and enchained Africans.

A disused mining ventilation chimney is seen close to Whitehaven near the site of a proposed coal mine on Oct. 4, 2021.Jon Super/AP

As we walked up Lowther Street, Peter shared his discomfort with nostalgic visions of English rural life. “The African continent was robbed,” he said, “and the fingerprints of the English countryside are all over the crime scene. No amount of warm beer, nuns on bicycles, and thatched roofs can obscure that.”

As Peter knew well, Whitehaven’s traders and enslavers did not just bring tobacco and sugar back with them. They brought enslaved people, too. The town’s history shows how the triangular trade, as it is sometimes called (British goods to West Africa, enslaved people to the Caribbean, then plantation produce back to Britain) was far more complicated than the three points suggests. Enslaved people were often trafficked from island to island and from continent to continent.

We reached the tower of St. Nicolas, a sandstone church that glows pink at sundown. Standing beneath the tower, we surveyed the elegant old square. The main, rebuilt church building was closed, but we wanted to visit the site because at least 66 people of African—and sometimes Indian—descent were baptized, married, or buried at St. Nicolas and at churches in Maryport, Workington, and St. Bees.

I had a copy of local archivists’ list of parish record entries, and Peter and I perused the names. In 1753, the parish register of St. Nicolas recorded that “Samuel, Son of a Female Negro Slave call’d Powers, a native of Carolina in North America” was baptized there. This brief record notes that he was connected to a family in the Cumbrian town of Kirby Lonsdale. In 1758, St. Nicholas Church also saw the baptism of a man whose name and identity followed the now-established tradition of renaming enslaved people after places in the British Isles: “Thomas Whitehaven,” reads the entry, “a Negro of ripe years.”

Eight years later, also at St. Nicholas, the burial took place of “Othello, a Black of Mr. John Hartley,” the slaver: “Othello” reflected the equally common practice of giving enslaved people literary names. Tiny fragments such as these testify to enslaved people’s exclusion from the historical narrative. So many unanswerable questions sprang to mind: Why were they here? What were their lives like? What did they think of Whitehaven and how did they change it? These glimpses of them are mediated by official figures.

By the time the act to abolish the slave trade was passed in 1807, the legacy of slavery had long since been felt along the Whitehaven coast, which was proportionately more multiracial in the 18th century than it is in the 21st. When, in 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed, a further Act of Parliament empowered commissioners to pay compensation to enslavers for their loss of property—but not the enslaved. In Whitehaven, the Hartley family claimed for 794 enslaved people in five Jamaican estates, which mostly produced sugar, molasses, rum, and pimento. Major slave owners, the Hartleys were respected townsmen, both manufacturers and bankers, and the compensation money was duly paid into the Hartleys and Co. Bank.

To anyone versed in British slavery compensation records, these Whitehaven stories feel familiar. “But what really counts is how places tell their stories,” Peter said. “You can tell a lot by looking at which stories get bigged-up and which are minimized or ignored.”

I thought of the National Trust’s description of the Whitehaven coast, which illustrates how celebrations of the landscape can obscure historical truths. Whitehaven’s mining heritage is mentioned, but the description focuses overwhelmingly on flora and fauna, including work by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to care for puffins and other seabirds. The sandstone cliffs, the Trust description reads, are among Britain’s tallest. There is no mention of tobacco or slave-trading at all.

Copyright © 2024 by Corinne Fowler. Originally published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen Lane as Our Island Stories. From the forthcoming book The Countryside: Ten Rural Walks Through Britain and Its Hidden History of Empire by Corinne Fowler to be published by Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC. Printed by permission.

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Take the Survey at https://survey.energynewsbeat.com/

ENB Top News

ENB

Energy Dashboard

ENB Podcast

ENB Substack