This commentary was submitted by Sneha Ayyagari, a Clean Energy Leadership Institute Fellow and a Program Manager for Clean Energy Initiative at the Greenlining Institute. See our commentary guidelines for more information.

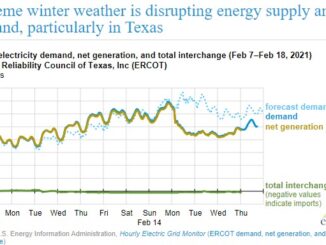

Winter is coming, and having resilient homes is crucial in climate disasters. For instance, Texans were woefully unprepared for Storm Uri which resulted in 246 deaths. While my family shivered under blankets, temperatures in our house stayed safe since we had insulation and a heat pump that kicked into gear when we had short periods of power. It was devastating hearing of families living in poorly insulated homes exposed to hypothermia. Weatherizing buildings and switching to efficient systems like heat pumps can be lifesaving in extreme weather and generally be more comfortable and can save residents money.

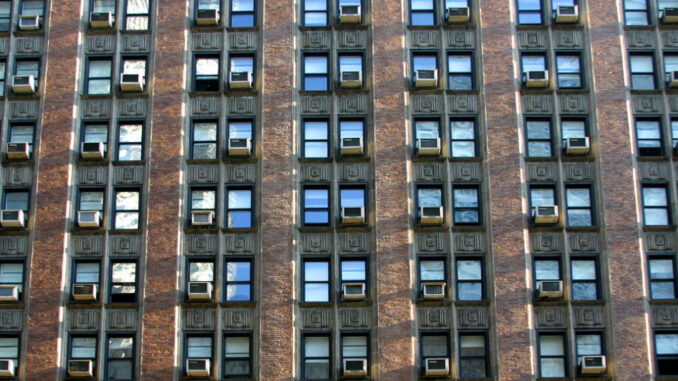

However, for more than a third of residents living in rental housing, accessing incentive programs that allow them to make these upgrades in their homes is very difficult. These barriers are especially high for residents in multifamily affordable housing and mobile homes where many people who are most susceptible to heat-related illnesses live.

States and local governments should implement federal funding with renters in mind. The Department of Energy’s Home Energy Rebates (HER) program provides $8.8B in rebate funding for energy efficiency and electrification projects and an additional $200M for states to develop complementary contractor training programs. States can provide their most vulnerable residents health, economic, and environmental benefits by prioritizing low-income renters in their applications for Home Energy Rebate funding.

To ensure the benefits of this program reach tenants, states should:

Renters should not have to fear that their landlords would use building upgrades as a reason to raise rents or displace them (as has happened in construction projects including apartment renovations in Los Angeles). At a minimum, HER guidance states that the owner must agree to rent the dwelling to a low-income tenant and cannot increase rent as a result of energy improvements for two years. Tenants must also have written notice of their rights in a specific and verifiable mechanism. States should go further to specify clear enforcement and penalties. They should ensure that tenants have access to legal services and support in reporting violations without fear of retaliation. Administrators should prohibit rent increases due to HER or at least extend the window of preventing rent increases to at least 10 years following the precedent of other programs.

In addition to building decarbonization programs, states should adopt policies such as rental efficiency standards, rental registries, eviction protections, and rent-stabilization measures to preserve affordability and increase the quality of rental housing. State and local renter protections such as California’s Transformative Communities Draft Program Guidelines and Berkeley’s Existing Buildings Electrification Strategy include a list of tenant protections and anti-displacement resources.

States have many resources from tenant advocates, environmental justice leaders, and policy groups to build from. This letter led by Just Solutions Collective in collaboration with 60 environmental justice, housing, workforce, and environmental organizations has detailed recommendations on reducing barriers for tenants. Strategic Actions for a Just Economy shared recommendations on developing a tenant protection plan to prevent rent burden, limit evictions, minimize disruptions to tenants, and design enforcement and penalty systems. The Greenlining’s Equitable Building Decarbonization Framework shares how to design a community-led approach to implementation. Just Solutions Collective provides recommendations on ensuring access to low income renters, and Green and Healthy Homes Initiative and Building Decarbonization Coalition shares lessons learned from past federal building retrofit programs. Other resources include American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s webinars and Energy Innovation’s report on ways to design effective outreach strategies.

Regional and local community based organizations should be compensated to be part of the program administration team and help with outreach, implementation, and evaluation of the Home Energy program. The HER application also requires that states create Community Benefits Plans that describe anticipated economic and direct benefits especially for disadvantaged communities. As states develop their community benefits plans, they should ensure that benefits to low income tenants are prioritized within the scope of the goals.

Stacking and braiding federal funding with other state, local, and utility housing, energy, and building retrofits programs can maximize benefits to renters while streamlining the effort of property owners applying for multiple programs. Philadelphia’s Built to Last and Washington’s Weatherization and Health are good examples of holistic programs.

Families shouldn’t have to choose between affording rent and having a safe and healthy place to live, especially in the face of climate disasters. States have a historic opportunity to drastically improve the lives of tenants. By collaborating with tenants, state energy offices can create strong applications in 2024 that ensure healthy, affordable, and climate-resilient housing for all.