Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The longed-for Fed pivot may come quicker than expected — especially after this week’s very soft inflation data — but equities still face more downside if hopes for easier monetary conditions clash with the rising risk of a recession.

The Fed’s battle with inflation this year has pitched the stock market into one its most bearish cycles in decades. The expectation — or hope — is that once the Fed takes its foot off the brake, stocks will cast off their shackles and new a bull market will take flight.

That doesn’t look likely. And that’s despite the fact that evidence is mounting that the Fed is at, or at least very close to, peak hawkishness.

Central-bank rhetoric has begun to soften, the midterms are now behind us, and market expectations of where the Fed rate will peak now consistently exceed the high-point implied by its so-called “dot plot” projections. With the market now helping, not hindering, the Fed in its monetary objectives, the central bank shouldn’t have to keep sharpening its talons for much longer.

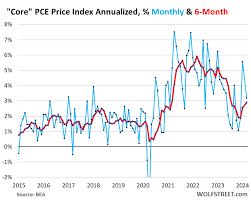

On top of that, the Fed pivot could come much sooner than most expect. The median length of time between the peak in inflation and the first rate cut is 22 weeks, according to US hiking cycles going back to 1972. June’s CPI print likely marks this cycle’s peak in headline inflation which, historically speaking, would put the first cut in as little as four to eight weeks.

This is not a prediction. But it does highlight how a Fed reversal could happen more quickly than the market expects. Either way, equity investors should treat it as the false dawn it is.

Firstly, financial conditions continue tightening for about five quarters after the first Fed hike. In the current cycle this would take us until the second half of 2023. Secondly, there’s a still greater squeeze in liquidity to come. The Global Real Policy Rate is still extremely negative and close to the all-time lows of -6% it reached in 1974, before it rose all the way to +3% by the early 1980s. Today it is at -4.4%, barely above its -5.6% nadir.

Overall, global financial conditions, as measured by the Global Financial Tightness Indicator, remain very restrictive, with no respite on the horizon. This will remain a poor environment for equities and other risk assets.

Even then, stocks might avoid the worst if the US dodges a recession, but the chances of that are rapidly diminishing as higher borrowing costs filter through the economy. As one of the most interest-rate sensitive sectors, housing is often first to feel the squeeze of those hawkish Fed claws.

As housing costs mount substantially, price growth is falling rapidly. Existing and pending home sales are declining fast. Mortgage rates have risen to 20-year highs, a trend that’s also contributing to the swift decline in growth of building permits. When residential building slows, it almost always leads to a weaker housing market and thus to a more fragile economy. The falling value of the homes they live in will also dent consumers’ confidence.

Used car prices, the poster-child of rapidly rising inflation last year, are collapsing in year-on-year terms as demand slumps. And credit conditions are deteriorating, leading to wider spreads, reduced liquidity and increased difficulty for borrowers in raising money.

Reliable leading indicators, such as the Philadelphia Fed State Diffusion Index and debit balances in customer margin accounts, are at levels that have always preceded recessions in the past. Even if the Fed were to start cutting rates tomorrow, an economic slump already looks to be baked in.

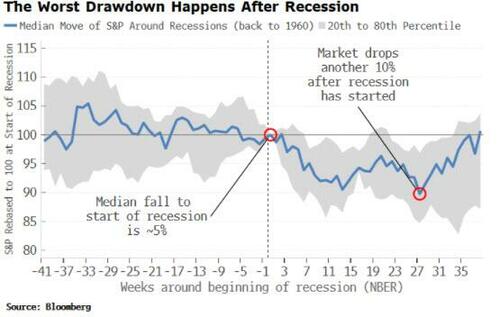

Have no fear you might say, with the market already down over 20% from its highs, a recession is already in the price. But that’s not what the past tells us.

Stocks are, in fact, pretty poor leading indicators, tending to sell off most once a recession has actually begun. Going back to 1960, the median sell-off of the S&P before the beginning of an NBER recession was 5%, but the market goes on to sell-off double that — 10% — in the months following the downturn.

Stocks may find themselves flipping from the inflation frying-pan into the recessionary fire, as the monetary easing the market has so desperately yearned for sets the stage for a new act, which promises to bring yet more misery.