ENB Publishers Note: There is a strong relationship between inflation and the use of renewable energy. The more renewable energy, the higher the inflation rate. ENB has research starting to show this relationship in world economies. This is an excellent article from Geopolitical Futures, and if you need to know great opinions and insights please join their ClubGPF today.

Post-pandemic economic growth in the European Union has gotten off to a solid start, with most of the bloc’s macroeconomic indicators having returned to pre-pandemic levels. But the recovery is threatened by inflationary pressure, mainly driven by rising energy prices, which shows no signs of abating – especially in light of the crisis in Ukraine. Companies are concerned about higher costs eating into profit margins, while consumers worry about its effect on their purchasing power. Both are looking to their governments for help, but officials have their own concerns about triggering an inflationary spiral. This dilemma, which every EU country faces, raises the likelihood of a major restructuring of national economies. A closer look at the German and Italian situations reveals how the different political climates and tools available will result in drastically different chances of recovery across Europe.

Life Before the Pandemic

Although there is a consensus that prolonged periods of high inflation are detrimental to any national economic recovery, states differ on where to draw the line and what to prioritize. Companies have been confronting the problem of narrowing profit margins for more than a year now. Logistical bottlenecks, large swings in consumer behavior and increased input costs have already driven up producer prices. Many firms may not remain profitable for much longer, and unprofitability puts the survival of the firm at risk. Meanwhile, European households worry that rising prices are eating away at their purchasing power and have started demanding that employers and governments alleviate the impact. These competing interests present EU governments with a real risk of a wage-price spiral, which occurs when firms and workers take turns responding to each other’s attempts to gain a larger share of revenues by raising prices and demanding pay raises (thereby increasing producer costs), respectively.

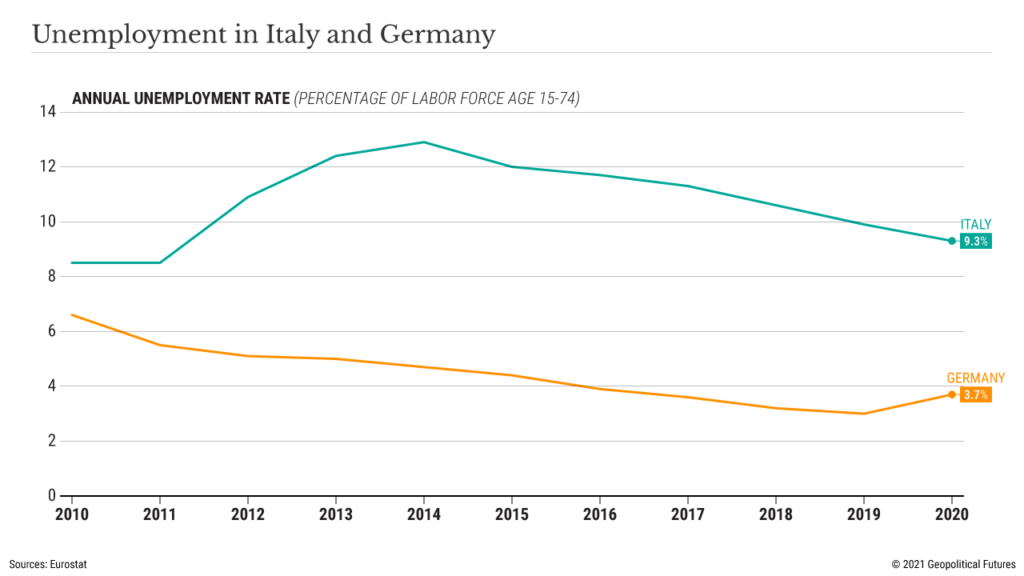

Eurozone governments cannot address inflation on their own, considering the 19-member bloc’s monetary integration and the role that the European Central Bank plays in maintaining price stability throughout the currency area. However, the purchasing power in each state is determined internally and affects the eurozone inflation rate accordingly. Before the pandemic, the ECB was busy trying to stimulate inflation to bring it closer to its former target of close to but under 2 percent annually. Unsurprisingly, differences between member states arose over government measures to reduce unemployment in the years following the eurozone crisis, accounting for the EU’s budgetary limits. For example, in Italy before the pandemic, the unemployment rate was 10 percent. (It peaked at approximately 13 percent between 2014 and 2015.) Youth unemployment was a staggering 28 percent, and there were significant regional disparities, which put further pressure on Rome, trapped between local demands and European rules. To support workers, for instance, Rome in 2018 adopted a minimum income welfare measure known as citizens’ income as well as an early retirement measure called Quota 100. Germany, on the other hand, had an average unemployment rate of around 5 percent before the pandemic. Unlike Italy, the German government did not need to engage in large-scale spending to support employment or household income.

The pre-pandemic approaches to unemployment illustrate the diverging political views over how the fiscal deficit should be handled and what its limit within the eurozone should be. The existing rule limits deficits to 3 percent of gross domestic product. Its purpose was to help maintain stability within the currency area. Observing this rule cuts into the type of programs governments have available to support and stabilize their economies. Moreover, with limits on public spending, governments must be even more scrupulous about how they distribute funds – whether to prop up companies’ profits or to pay consumers. Their answer to that question depends on the economy’s composition and internal political dynamics.

But then the pandemic came, and in the midst of the ensuing emergency, the goals of Berlin and Rome were very similar: to contain the damage of the economic downturn. In the short term, this meant implementing measures to maintain the incomes of households forced to stay at home and of firms forced to close – with little regard for inflation or budgetary limits, which were suspended at the EU level to free up space for public interventions.

In Italy, the pandemic package was known as the Cure Italy Decree. It introduced indemnities and bonuses worth approximately 100 billion euros ($113 billion) to put more money in consumers’ pockets. An emergency income was also adopted for families under a certain income threshold, and the collection of some taxes was de facto postponed. In Germany, the government directed more support toward companies than consumers. First, it temporarily reduced the value-added tax, in which consumer purchases help fund the payment of a company’s tax liabilities. Berlin also introduced assistance packages to support microenterprises, small and midsized employers and their employees, and the self-employed and freelancers. State-owned investment and development bank KfW issued loans.

Recovery and Inflation

The economic reopening and consequent economic rebound made possible the gradual reduction of government programs, without any major political backlash. In Italy, unemployment is now around 9 percent, a significant improvement compared with the years prior to COVID-19. In Germany, it was slightly over 5 percent but falling. Therefore, Rome and Berlin have begun to scale back some emergency social measures. For instance, Germany recently ended its VAT cut, and Italy will likely not extend the emergency income in 2022. Rome also probably won’t continue the delay of tax payments.

However, inflation has been building for months amid persistent supply chain disruptions and consequent supply bottlenecks. As prices continue to soar, particularly in the energy sector, workers are concerned less with employment and more with wages. In particular, labor unions have become more active. The low inflation environment that preceded the pandemic was not conducive to mass organized labor activity, but inflation’s return has changed that. In Italy and Germany, unions are calling for inflation expectations to be factored into wage negotiations. This reactivation of unions is important because it intensifies political pressure on governments and affects policy decisions.

Another factor putting upward pressure on wages is labor shortages. Germany’s workforce is forecast to shrink by 300,000 in 2022, and labor shortages would reach 5 million by 2030 if they continued at the current pace, according to estimates by the German Economic Institute. In Italy, the phenomenon is confined to specific sectors, such as tourism, hospitality and health, but these sectors are significant – in 2019, tourism accounted for 13 percent of Italy’s GDP. As firms struggle to attract workers, they may be forced to raise wages.

The End of the United Response

With pressure on governments mounting, it’s likely that both Germany and Italy will introduce measures to mitigate the effect of inflation on workers. Which strategies they adopt, however, will vary drastically.

With a general election scheduled in the first half of next year, Italy will be more deferential toward the demands of workers. The already fragile government coalition, made up of all the major parties but one, is already under pressure to extend the bonuses and indemnities. Failing to address households’ concerns over rising prices would damage the support of every party in the coalition, cementing the rise of the only opposition party – which is also the most euroskeptic party.

Italy is also a country that is not generally averse to inflation. Before adopting the euro, Rome often employed currency devaluations to gain international competitiveness and keep unemployment contained.

Germany, on the other hand, will be more focused on containing inflation. Germany is an export country, and rising input prices – labor, in this case – mean final output prices will be higher. Products with higher prices lose competitiveness, jeopardizing Germany’s export model.

The discrepancy over public spending among different EU member states will once again be on full display. With its high public debt levels, Italy has very little fiscal room for maneuver to implement additional social welfare policies. It cannot rely on EU money from the pandemic recovery package to extend bonuses and sustain wages, because the so-called Next Generation EU money must be used to address structural deficiencies (e.g., infrastructure, regional cohesion, health care, research and development, digitization). Instead, it will likely need to increase its already enormous deficit and debt levels. This will inevitably put it at loggerheads with its northern eurozone partners like Germany, especially since EU fiscal limits are set to be reintroduced at the end of 2022.

Germany, meanwhile, has more fiscal room within eurozone budgetary limits. For starters, it suspended its constitutional rule that limits deficits. This move benefits German companies and facilitates a more orderly restructuring in the wake of the pandemic. Berlin has also proposed increasing the minimum wage in order to keep pace with, but not surpass, inflation. While there is no guarantee the German government will follow through, the newly elected government has little political wiggle room and needs to appear as if it is trying to make good on its campaign promises.

These differing approaches to inflation and unemployment will yield different results, and Germany looks better positioned than Italy to weather the storm. First, Germany has more options for supporting companies than Italy, which had to resort to more direct social payouts. Italy’s services-based economy also looks likely to suffer more bankruptcies than export-oriented Germany, which has international trade to fall back on.

By – Francesco Casarotto – Geopolitical Futures