Natural gas isn’t the only power-plant fuel on fire this year. Thermal-coal prices have soared from Appalachia to Australia, threatening more increases in manufacturing costs and power bills this summer.

Futures for coal delivered to northwestern Europe have risen 137% so far this year, to $323.50 a metric ton as of Wednesday. The benchmark price in the Pacific region, set at an Australian export facility, is up more than 140% this year. Cash prices in central Appalachia have climbed 40% in 2022—and more than doubled over the past year—to $129.65 a short ton last week, the highest price on record.

Power demand has come roaring back from the pandemic to drive the gains, as has Russia’s war in Ukraine, which prompted European electricity producers to stock up ahead of a ban on coal exports from Russia starting in August.

Meanwhile, investment in mining has dwindled in the midst of expectations that coal would keep losing market share to renewable sources, such as wind farms, and cleaner-burning natural gas.

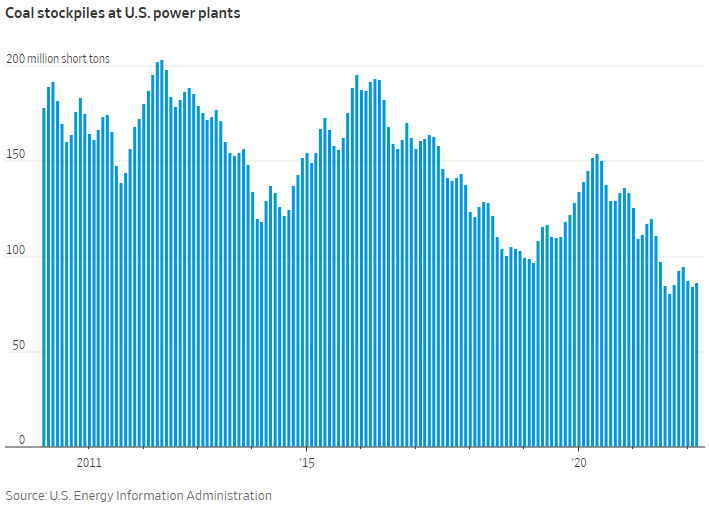

That has left inventories low.

In the U.S., coal stockpiles at power plants in September hit their lowest level since the 1970s and have been kept down by strong demand. Power-plant coal inventories were about 44% below the 13-year average in March, according to the Energy Information Administration’s most recent data.

“Not only is the domestic market looking for coal for power generation, but international markets are as well,” said Andy Blumenfeld, data analytics director at McCloskey by OPIS. The pricing service is part of News Corp’s Dow Jones & Co., which publishes The Wall Street Journal.

Though coal production is expected to rise this year compared with last, utilities are having trouble finding the fuel, given the congestion at railheads and ports. Financing for speculative coal production has dried up in recent years. Miners now sell most of their output in advance.

“A lot of the mining companies are very close, if they’re not already, to being sold out for this year,” Mr. Blumenfeld said.

Normally the fix for high coal prices is to switch to burning more natural gas, which is the leading power-generation fuel. But gas prices have popped up since the pandemic, for reasons similar to coal. U.S. natural-gas futures are up 127% so far this year and have been trading at their highest level since 2008.

High prices for both coal and natural gas have obviated the need for fuel switching among power producers and made for fairly inelastic markets in the electricity business, said Sheetal Nasta, an analyst at RBN Energy.

U.S. electric bills have soared, and are likely to move higher as households break out their air conditioners. WSJ’s Katherine Blunt explains why electricity and natural-gas prices are up so much this year and offers tips on how to manage the expense.

“As long as the gas market remains tight and coal remains unavailable to pick up incremental power demand, there’s no limit to how high prices for both fuels could go,” she said.

Coal demand is also being buoyed by slower than expected development of renewable-energy installations. The U.S. power sector has retired about a third of its coal-fired generating capacity since 2010, and another 6% is scheduled to go offline this year. Some of those closures are being rescheduled, though.

Utility owner NiSource Inc. said last month that it would push back until the end of 2025 the retirement of two coal-burning units at an Indiana generating station, which were scheduled to be shut down by the end of next year and their output replaced by solar farms. NiSource said it would keep burning coal while it waits out delays in constructing the solar plant, which it attributed to a Commerce Department investigation into whether Chinese solar producers are illegally circumventing tariffs by routing operations through other countries.

Source: Wsj.com