One study estimates that covering California’s canals with solar panels could generate enough energy to power Los Angeles for most of the year.

Back in 2015, California’s dry earth was crunching under a fourth year of drought.

Then-Governor Jerry Brown ordered an unprecedented 25 per cent reduction in home water use. Farmers, who use the most water, volunteered too to avoid deeper, mandatory cuts.

Brown also set a goal for the state to get half its energy from renewable sources, with climate change bearing down.

Yet when entrepreneurs Jordan Harris and Robin Raj went knocking on doors with an idea that addresses both water loss and climate pollution – installing solar panels over irrigation canals – they couldn’t get anyone to commit.

Fast forward eight years. With devastating heat, record-breaking wildfire, looming crisis on the Colorado River, a growing commitment to fighting climate change, and a little bit of movement-building, their company Solar AquaGrid is preparing to break ground on the first solar-covered canal project in the United States.

“All of these coming together at this moment,” Harris said. “Is there a more pressing issue that we could apply our time to?”

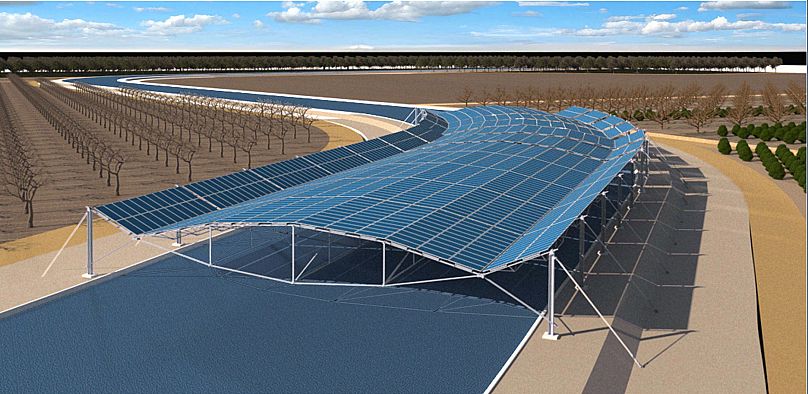

The idea is simple: install solar panels over canals in sunny, water-scarce regions where they reduce evaporation and make electricity.

A study by the University of California, Merced gives a boost to the idea, estimating that 63 billion gallons of water could be saved by covering California‘s 6,437 kilometres of canals with solar panels that could also generate 13 gigawatts of power. That’s enough for the entire city of Los Angeles from January through early October.

But that’s an estimate – neither it, nor other potential benefits have been tested scientifically. That’s about to change with Project Nexus in California’s Central Valley.

How long have solar canals been in the works?

Solar on canals has long been discussed as a two-for-one solution in California, where affordable land for energy development is as scarce as water. But the grand idea was still hypothetical.

Harris, a former record label executive, co-founded ‘Rock the Vote’, the voter registration push in the early 1990s, and Raj organised socially responsible and sustainability campaigns for businesses. They knew that people needed a nudge – ideally one from a trusted source.

They thought research from a reputable institution might do the trick, and got funding for UC Merced to study the impact of solar-covered-canals in California.

Published in 2021, the study’s results are catching attention. They reached Governor Gavin Newsom, who called Wade Crowfoot, his secretary of natural resources.

“Let’s get this in the ground and see what’s possible,” Crowfoot recalled the governor saying.

Around the same time, the Turlock Irrigation District, an entity that also provides power, reached out to UC Merced. It was looking to build a solar project to comply with the state’s increased goal of 100 per cent renewable energy by 2045. But land was very expensive, so building atop existing infrastructure was appealing.

Then there was the prospect that shade from panels might reduce weeds growing in the canals – a problem that costs this utility $1 million (around €900 mn) annually.

“Until this UC Merced paper came out, we never really saw what those co-benefits would be,” said Josh Weimer, external affairs manager for the district. “If somebody was going to pilot this concept, we wanted to make sure it was us.”

The state committed $20 million (€18 mn) in public funds, turning the pilot into a three-party collaboration among the private, public and academic sectors. About 2.6 kilometres of canals between 20 and 110 feet wide will be covered with solar panels between five and 15 feet off the ground.

The UC Merced team will study impacts ranging from evaporation to water quality, said Brandi McKuin, lead researcher on the study.

“We need to get to the heart of those questions before we make any recommendations about how to do this more widely,” she said.