Amid a deluge of terrifying headlines about destructive tornadoes, blistering heat waves and DVD-sized gorilla hail, here’s a surprising bit of good news: Global carbon dioxide emissions may have peaked last year, according to a new projection.

It’s worth dwelling on the significance of what could be a remarkable inflection point.

For centuries, the burning of coal, oil and gas has produced huge volumes of planet-warming gasses. As a result, global temperatures rose by an average of 1.5 degrees Celsius higher than at the dawn of the industrial age, and extreme weather is becoming more frequent.

But we now appear to be living through the precise moment when the emissions that are responsible for climate change are starting to fall, according to new data by BloombergNEF, a research firm. This projection is in roughly in line with other estimates, including a recent report from Climate Analytics.

Thanks to the rapid build-out of wind and solar power plants, particularly in China, global emissions from the power sector are set to decline this year. Last year, the amount of renewable energy capacity added globally jumped by almost 50 percent, according to the International Energy Agency.

And with the rise of electric vehicles and heat pumps, similar gains are anticipated in the transportation sector and residential buildings.

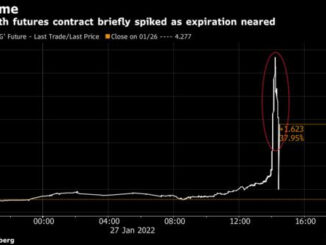

Forecasting emissions is an inexact science. Greenhouse gas levels fell during the Covid-19 pandemic, then spiked as the world emerged from lockdown. Other wild cards, such as melting permafrost or huge wildfires, could further scramble projections. Nevertheless, the data suggests that after centuries of growth, humans are finally on the cusp of reducing the overall production of heat-trapping gases.

The decline in emissions will not be swift. Even if every government and business in the world made combating climate change a top priority, it would still take at least two decades, and an estimated $215 trillion, to make a full transition to an emissions-free world.

Doing so, the report said, would require the immediate adoption of what would essentially be a wartime approach to constructing renewable energy and subsidizing low-carbon technologies, and a set of strict regulatory measures designed to curb emissions-heavy modes of transportation, energy production and industry. For example, BloombergNEF projects that no new internal combustion engine vehicles could be sold after 2034.

In such a scenario, the BloombergNEF report forecasts that it may be possible to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, resulting in an average global temperature rise of 1.75 degrees above preindustrial levels.

At the other end of the spectrum, the report spells out what it calls the “economic transition scenario,” which is more or less business as usual.

On this path, clean energy will be cheaper as current policies and subsidies continue to promote some efforts to reduce emissions. But in this scenario, overall emissions will fall just 27 percent from current levels by 2050. As a result, global average temperatures will rise some 2.6 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a level of warming that scientists say will lead to steep sea level rise and even higher temperatures.

This is the scenario oil companies are preparing for. Oil companies have brought in record profits in recent years, and the demand for energy is surging around the world. Governments are approving new oil and gas projects, effectively locking in decades of additional emissions. And even as wind and solar power produce more electricity, fossil fuel executives forecast durable demand for their products.

Over the past year, some of the biggest fossil fuel companies in the world struck deals in a bid to expand their reach. Exxon Mobil last year signed a $60 billion deal to buy Pioneer Natural Resources. Then Chevron agreed to acquire Hess for $53 billion. And yesterday, ConocoPhillips agreed to buy Marathon Oil for $22.5 billion.

As those deals make clear, the fossil fuel business isn’t going away anytime soon. “Who is going to replace jet fuel?” Scott Sheffield, the chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, told my colleague Clifford Krauss last year. “Who is going to replace petrochemicals? What alternatives will replace all that?”

Nevertheless, it appears inevitable that in aggregate, fossil fuels are set to decline. The International Energy Agency expects global demand for both oil and gas to peak by 2030.

“This is the last gasp of the fossil fuel industry,” said Tzeporah Berman, founder of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, a movement that seeks to phase out coal, oil and gas. “They read the writing on the wall. They know that their days are limited. And they’re doing everything they can to make sure that they are the last barrel sold.”

Getting to net zero by 2050 is a virtual impossibility without extraordinary efforts to reduce emissions around the globe. It’s also not a given that we’re stuck with the “economic transition scenario” outlined by BloombergNEF. Instead, the reality is probably somewhere in between. How fast we stop producing planet warming gases depends on many different factors.

Chief among them is China. The world’s second-most-populous country is currently the biggest emitter on the planet. More than 60 percent of China’s energy supply comes from coal, according to the I.E.A. At the same time, China is also doing more than any other country to develop solar panels and electric vehicles.

The BloombergNEF report suggests emissions in China may peak this year, and then begin a gradual decline. A recent report from Carbon Brief also signals a potential peak in Chinese emissions.

Other factors include the raft of elections across the world this year, permitting reforms, lobbying by fossil fuel companies, global conflicts, corporate efforts to reduce emissions, consumer behavior and emerging technologies, to name just a few.