China and Russia have a great deal in common. Both are authoritarian states, both lost territory in the twentieth century, and both are set on redressing those losses. Both are critical players in the world’s energy markets, howbeit for very different reasons, and both see the US as “the enemy”. Both are nuclear powers, and both have heavy military expenditure.

The similarities can of course be pushed too far: China is a rising power based upon a rising economy; Russia is much smaller in almost every respect. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russia has become dependent on China, and in many ways has become something of a vassal state.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 follows on from its more tentative moves in annexing South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and then Crimea. It has long been obvious – expect perhaps to those in charge of German foreign policy – that Russia’s sights are set immediately on securing Belarus and Ukraine within its embrace, and, as the Baltic states have recognised, they are the next logical step for as long as Putinism survives.

In the Ukrainian case, Russia can point to past occupation, and if it goes far enough back, Kiev as the capital of the Russian people, long before Stalin inflicted mass famine on its population. In China’s case, first it has been the re-integration of Hong Kong into the Communist Party’s embrace, and next up is Taiwan, the last refuge of Chiang Kai-Shek in the Chinese revolutionary war that Mao won. In neither case is the will of the people in Ukraine and Taiwan, respectively, any part of their concerns.

In the case of Taiwan, it is hard to think that China could ever give up its claim and recognise the democratic right of Taiwan’s people to choose their own fate. On the contrary, the current leader has made his intentions crystal clear. It is a question of when, not if, and the signs are that it is going to be sooner rather than later.

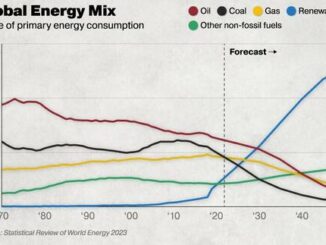

What is also crystal clear is that preparation for the fallout in energy markets is notable by its absence. With uncanny similarity to the Germans pursuing Nord Stream 1 and then 2, deliberately (in Putin’s case) aiding Russia’s isolation of Ukrainian gas pipelines in the process, the EU and the US are merrily increasing their dependency on China for the critical minerals for the net zero transition, and increasing dependency on Chinese solar panels and wind turbines and much else. The control by Russia of gas into Europe hit very hard; a parallel dependency is building for the energy of the future. Every day that dependency grows.

The scale of the shock

Assume for a moment that China launches a full invasion tomorrow, and imagine that the Taiwanese people and its military do not surrender instantly, as the Ukrainians were supposed to do within ten days in February 2022. Imagine the headlines, imagine the political response, and imagine the economic fallout.

It is reasonable to suppose that there would be immediate big falls in financial markets. Investors would run for cover as the great supply chains built up in the last three decades fell apart. The dollar would rise, US Treasuries would rise, and most likely there would be a big recession to follow. Given the instabilities already built up in the pack of asset cards constructed on the back of negative real interest rates over the last two decades, two reasons for a crash would coincide. It could be the mother of all financial crises. Inflation might worsen too, as goods and services costs rise in the scurry for non-Chinese goods.

That first macroeconomic shock would be even bigger if the US plus or minus allies retaliated militarily. Japan and Australia would see themselves as the next targets and, even if they did not join the battle, would separate themselves more forcefully from China and, in Japan’s case, rearmament would accelerate. The response of the UK might be similar to that to the Vietnamese War, cheering on, but with no actual military engagement.

Of course, it probably would not come to this, but, even in the rapid surrender case, there would be huge pressure to wean the EU and US off Chinese minerals, the refining of those minerals, and a great deal of trade. The world’s economy would morph further towards great power blocs, increasingly isolated from each other, and playing for friends and allies amongst what used to be called the non-aligned developing countries. This would especially extend to forcing the Middle Eastern oil and gas producers to choose sides.

Lessons from Ukraine not learned

After the shock of the great European gas crisis, you might think that lessons had been learned, the security of supply playbook would now be ready to roll out more generally, and, having been caught asleep at the geo-political wheel over Ukraine, there would be no mistake second time around.

You would be wrong, just as you would be wrong to believe that the world is well placed to handle the next pandemic, now that the coronavirus is no longer an international emergency.

The depressive history of the gas price crisis is that it has followed the usual pattern: denial, panic, relief and then complacency.[1] The gas price crisis is probably over, as European gas prices return to their five-year average. Electricity prices are starting to come down, and so will the inflation and the affordability crisis.

The remarkable thing about the gas crisis is that almost nothing has been learned, except for the political leaders to double down on what they are already doing. Ludicrous conclusions are drawn – that we should all try to get out of the future threat of high and volatile gas prices, just to make sure that we do not benefit from low and stable gas prices that are very likely to follow. It is the sort of mistake made in previous crises. In the great oil shocks of the 1970s and especially in 1979 with the Iranian Revolution, there was a great attempt to “get out of oil”, and hence to reduce the benefits of the two decades of rock-bottom prices that followed.

The energy policy challenges of China

To be fair, the US has recognised that dependency on China is a threat, and the Chips Act, the Infrastructure Act and the (grossly misnamed) Inflation Reduction Act are targeted at starting to build up US supply chains in critical minerals and refining. The US also has the luxury of abundant cheap fossil fuels – so much so that it is now supplying 50% of the EU’s liquefied natural gas (LNG).

It is a start and in money terms a significant one. The US and several European countries are also beginning to tentatively disentangle from the Chinese information systems – from Huawei and TikTok and the pervasive types of mass surveillance risks that China’s monitoring experiment on the Uighur people has demonstrated.

But when it comes to the great minerals of the future – lithium, nickel, copper and cobalt – the US has a long way to go to build up both the (colossal) mining required and the refinery capacity. For so-called rare earths, it is an even greater mountain to climb, and is even more China-dependent. The manufacture of solar panels, electric cars, batteries and wind turbines has a lot of catching up to do too.

Going forward, in addition to these incremental steps, what is really required is to redefine security of supply and the associated resilience that would give the US and Europe the ability to survive a Chinese shock post the invasion of Taiwan.

Security of supply turns out to be about the full supply chains, about strategic stockpiles, about fully integrated electricity systems. An energy-independent country would have its own mining and mineral supply chains and with “friendly” countries, it would have its own refining capacity, its own strategic stockpiles, and then its own battery manufacturing capacity, its own wind turbine manufacturing capacity, its own electric car factories, transmission and distribution cabling, and so on.

To see how far adrift current policy is, consider the Powering Up Britain paper produced by Grant Shapps, Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, at the end of March 2023.[2] All of the above requirements are given lip service at best. Despite the government’s claims, there is no credible mineral strategy, and almost nothing to give confidence in the supply chains. Instead, there are lots and lots of claims about “zero emissions” without much understanding of what actually goes into making the batteries, the electric cars, the network upgrades, and the wind turbines and solar panels. At minimum there should be a credible and robust analysis of how much of all this is “made in China” and a plan to deal with what happens if this supply chain suddenly gets ruptured.

The dangers of the gradualist approach

A twist to this dependency is that the more the US and Europe signal their intentions to gain a bit more independence from China, the greater the imperative for China to get on with the invasion of Taiwan. This incentive problem was all too apparent with Russia and Ukraine. As the Germans had fallen for the Nord Stream pipelines, and hence increased their reliance on Russian direct supplies, and the more the Germans under Merkel and then Scholz followed the Schröder line of believing that Russia would always be a reliable supplier of oil and gas (and much else too on the minerals and refining front), the timing for Putin got better and better.

Putin was led to believe that the Germans would squeal quickly when it came to sanctions and would undermine the EU’s support for Ukraine. Assuming, too, that the invasion of Ukraine would all be over in around ten days, that the Ukrainian government would capitulate and sue for peace, and a puppet government could be put rapidly in place were classic mistakes of an autocrat who loses contact with reality and is told only what he wants to hear.

China must be banking on a somewhat similar narrative – a quick victory, and a very quick subsuming of Taiwan into China. And, as with Russia’s timing on Ukraine, the current great dependency on China might just weaken as a result of deliberate policies by the US in particular. The more successful the US and the EU are at disengaging and building energy supply chains that are non-Chinese, the more emboldened the Taiwanese may become and the greater the economic fallout in China. Paradoxically, the gradual US moves and the much more feeble ones in the EU and the pathetic ones in the UK might accelerate China’s invasion plans. If it happened tomorrow morning, the impact on all those shiny net zero plans would be stark.

De-coupling the supply chain

What should governments do? The first and obvious step is to learn the lessons from Ukraine. Instead of denial, followed by panic, then relief and finally complacency, the moment for action is actually as the immediate crisis passes. It takes time to decouple, and the right way to go about this is to set out where you want to get to – what a secure energy system that is decarbonised should look like – and then to work back to the steps needed to get from here to there.

This is almost the opposite to what the Powering up Britain paper actually says. It is all about the net zero outcome, and silly stuff about the “cheapest energy in Europe”. (In public Grant Shapps drops the wholesale prices reference.)

Start at the beginning with the mining and minerals, move to the refining capacity, then to batteries and storage, and only finally to the electricity generation, electric cars and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The political difficulty with all this – for Shapps and Labour’s Miliband too – is that going from a fundamentally insecure energy system to one with a semblance of security is going to be costly – very costly. It is not just about the investments in nuclear, wind and solar generation, but about investing in the whole supply chain. Since there is very little UK savings to finance the huge investment required, and since UK consumers are not prepared for the rising bills that will need to pay the interest and dividends and repay the capital to all the foreign investors who will be the main source of that financing, the gap between the “cheapest energy” and what it might actually cost is going to come as a very big shock.

If there are any lessons from the history of energy policy, this sort of fundamental resetting of energy policy will not come before a crisis but after one, and only if that crisis lasts long enough and is painful enough to inflict real damage. It turns out that even the European gas crisis is not enough to do the job. A China crisis as it invades Taiwan might well be of a different order of magnitude. The hope is that ministers will wake up to what may be coming and prepare. But history suggests otherwise.