WILHELMSHAVEN, Germany—A long-submerged problem is complicating Germany’s attempts to wean itself off the vast pipelines pumping gas from Russia: Over a million tons of weapons and explosives rusting at the bottom of the sea.

Berlin plans to build three liquefied-natural gas terminals along its northern coast to break its dependence on Russian energy as the war in Ukraine grinds on. The idea is to ship gas in from the U.S., Canada or Qatar instead, diversifying Germany’s energy supplies as Moscow throttles deliveries, squeezing manufacturers and the rest of the German economy.

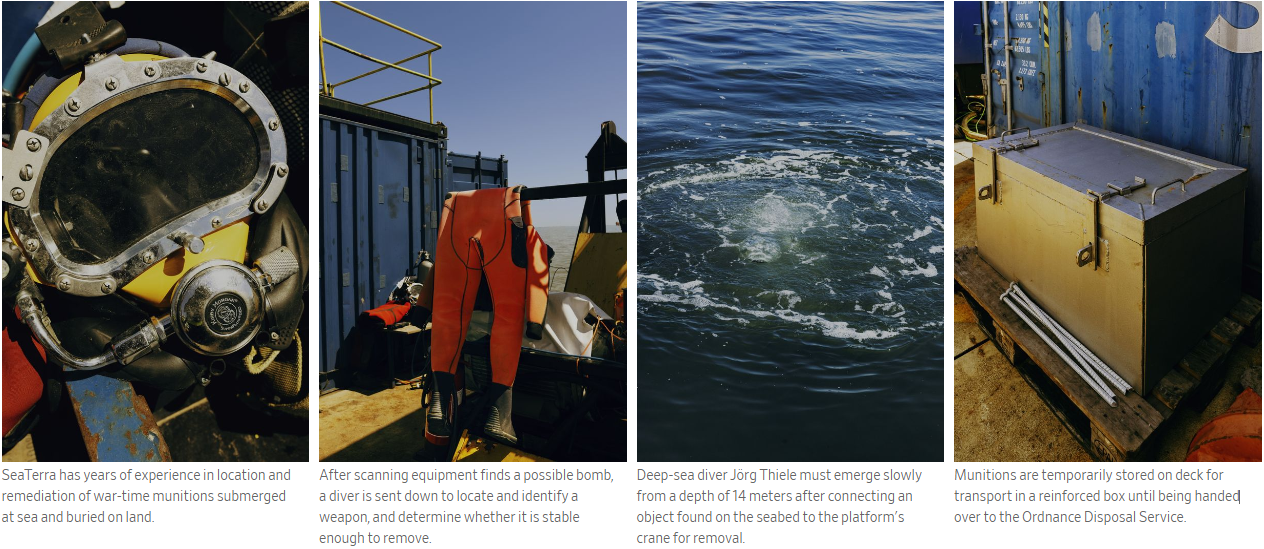

But before the terminals can start taking shipments, specialists such as Dieter Guldin and his company SeaTerra GmbH will have to find and remove all the unexploded wartime ordnance, or UXOs, surrounding the sites. There could be a lot.

“We’ve found something,” said Mr. Guldin as he ferried a visitor from the harbor out to the bomb removal platform stationed offshore. “It’s probably just junk. But we have to remove every piece of metal we find because it could be a bomb.”

Mines sunk in World War II

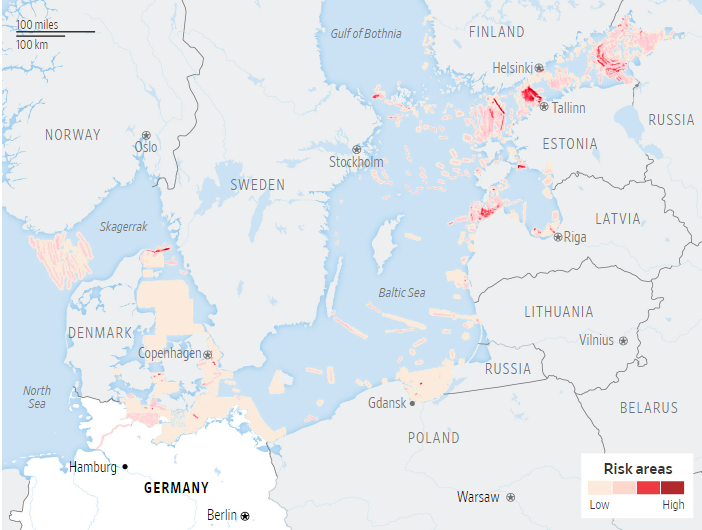

Much of Europe still bears traces of World War II in the form of unexploded ordnance, but the problem is especially acute in Germany, where an estimated 1.6 million tons of weapons and explosives were dumped in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Most were put there after the war, when Allied commanders ordered the destruction of Germany’s stockpiles of weapons. Now the UXOs, from large cannon-fired grenades to torpedoes and sea mines, are setting back new developments, including offshore wind farms.

One project, TenneT TSO GmbH’s Riffgat wind park, went online a year late in 2014, after 30 tons of World War II munitions had to be cleared to lay the cable connecting the turbines to the grid onshore.

The problem is becoming more pressing as Germany moves to adopt a broader mix of energy supplies, creating an opening for professional bomb-hunters.

“We are dealing with a ticking time bomb,” said Jann Wendt, CEO and founder of north.io, a tech company that is developing technology to map lost munitions on the ocean floor.

One of the proposed sites for the new liquefied-natural gas terminals is Minsener Oog, the first of a chain of East Frisian islands that hug the northern German coast west of Wilhelmshaven, home to Germany’s largest naval base and a small commercial harbor.

There are an estimated 10,000 tons of munitions in the area. To reach the site, ships have to make a hard right turn through a narrow passage past the weapons-dump site. The presence of the explosive has already delayed pre-Ukraine war plans to widen the shipping lane.

“Before the shipping lane can be widened and straightened in the area the old munitions must be removed,” said Marcus Grünwald, who is directing the local Waterway and Shipping Office project to clear the bombs. The acute danger, he said, is largely if a ship were to veer off course and drop anchor, accidentally detonating the munitions.

Recent findings suggest there could be a much larger dump site nearby along the Hooksiel Plateau, just south of Minsener Oog and close to Wilhelmshaven port.

“There are probably 300,000 tons of munitions about three or four kilometers away from Wilhelmshaven, a big hot spot,” says Uwe Wichert, a military historian who advises the state of Schleswig-Holstein and the Helsinki Committee, a group of Baltic countries that work to improve the environmental quality of the Baltic Sea. “No one knows for sure,” how many munitions there are, he said.

Mr. Wichert relies on British military archives and local harbor logs. The British controlled the northern ports after the war and initiated much of the effort to dispose of weapons stockpiles at sea.

But while the biggest dump sites are known and vessels aren’t allowed to pass over them, there are few records about where else the ammunition was dropped. Allied commanders often paid German fishermen to haul weapons out to dump sites. Paid by the load, many off loaded their bombs randomly so they could hurry back to take another shipment, according to transcripts of government interviews with fishermen in 1970.

A fisherman who transported three shipments of weapons from Flensburg to the mouth of the Kleine Belt fiord near the German-Danish border said these were just tossed overboard on the way to the Belt and back, according to a government interview transcript dated Sept. 14, 1970.

Using these sources, German authorities have managed to locate materiel that were dumped under the supervision of the western Allies, but there are gaps. There is no reliable information about weapons or munitions that the former Soviet Union might have dumped into the Baltic Sea.

The Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission, or Helcom, has been working for years to unite all Baltic nations in an effort to clean up the Baltic Sea, including old munitions. The group formally stopped meeting in February, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

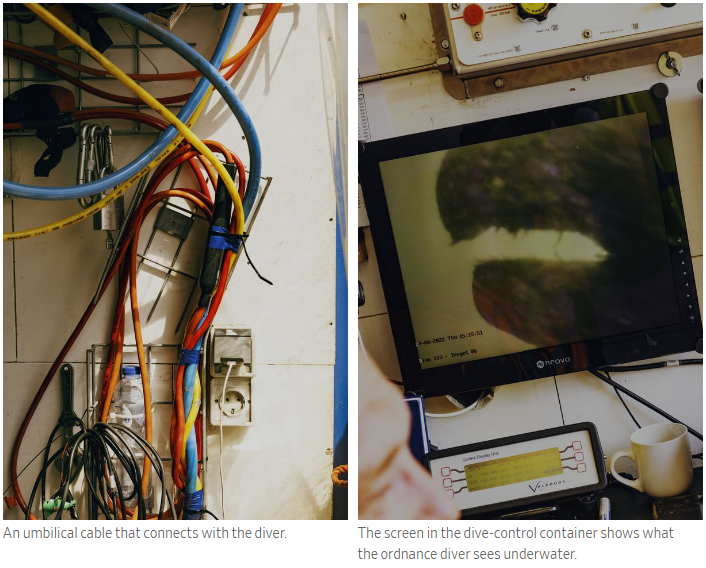

Until now, finding and removing the munitions has been tedious. Often, after scanning equipment finds a possible bomb, a diver is sent down to locate and identify a weapon, and determine whether it is stable enough to remove. In some cases, the ordnance is detonated on site, which removes the danger of unexpected explosions but risks spreading toxic pollution.

A study of the Kolberger Heide, one of the biggest dump sites in the Baltic Sea, found concentrations of toxins in shellfish living on or directly next to munitions so high that the author, Edmund Maser, director of the Institute of Toxicology and Pharmacology for Natural Scientists at Kiel University, Germany, told a parliamentary hearing that the shellfish posed a cancer risk and shouldn’t be eaten.

Abandoned munitions might also be having an impact on fish stocks, Mr. Maser said. Fish like structure in the open water, it is often where they spawn. The nooks and crannies in rocks or the spaces between piles of torpedoes, sea mines, and bombs. Mr. Maser said his studies show that the levels of toxins found in dump sites kill the eggs and young fish, which could shrink fish populations.

While experts agree that the underwater dump sites pose an environmental hazard, it is the economic risk posed by the weapons that is creating a new sense of urgency.

Gabriel Felbermayr, president of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, an economic think tank, says as much as 15% of Germany’s GDP and 3.5 million jobs depend on maritime transportation. A serious accident could shake confidence in shipping in the region, he said.

“One big event suffices to shake an entire economic ecosystem,” he said. “We clearly need public action.”

The German government has for the first time earmarked a small budget to create a pilot project to test the use of modern technology to systematically clear entire dump sites instead of using today’s piecemeal process.

Mr. Guldin of SeaTerra, and rivals, such as Thyssenkrupp Marine Services, are working on prototypes for a floating bomb detection-and-removal platform that would remove the munitions from the seabed and burn them on board. This would be a new way of cleaning up the sites that could accelerate the process. They say this could be done without releasing toxins in the environment.

One of the first test beds for similar technology is likely to be off Minsener Oog. The German government is planning to support a pilot project there to test whether the cleanup can be scaled up. If approved, the work would begin by 2024, speeding up the process of removing UXOs.

Alexander Orellano, chief operating officer of Thyssenkrupp Marine Systems, predicts that one such platform could dispose of three tons of munitions a day.

“That means it would take 1,000 years to get rid of all the weapons,” he told a conference in September. “We would need 100 of them to cope.”

European Union leaders took a big step in the economic fight against Moscow over its invasion of Ukraine by agreeing to block 90% of Russian oil imports by year-end. The embargo faced opposition from countries highly dependent on Russian crude, especially Hungary

Source: Wsj.com