The US government is getting ready to unleash $27 billion to fund projects in disadvantaged communities that cut greenhouse gas emissions and boost clean energy. The cash infusion from last year’s sweeping climate and tax law is meant to drive the deployment of solar panels, heat pumps and electric vehicles in underserved places around the nation.But even before the government formally seeks funding applications, hundreds of potential recipients are jockeying for the money. The competition pits credit unions and community development institutions against a national not-for-profit organization that says it should collect much of the haul and be a clearinghouse for the taxpayer dollars, making it the first-ever US-government-minted green bank.

Within days, the Environmental Protection Agency is expected to render its verdict on the best funding scheme, with a formal request for proposals that will signal its plans for doling out the cash in just a few months. The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, as it’s known, is one of the biggest single pots of money in a broader climate law that dedicates upward of $370 billion to advancing clean energy and fighting climate change.

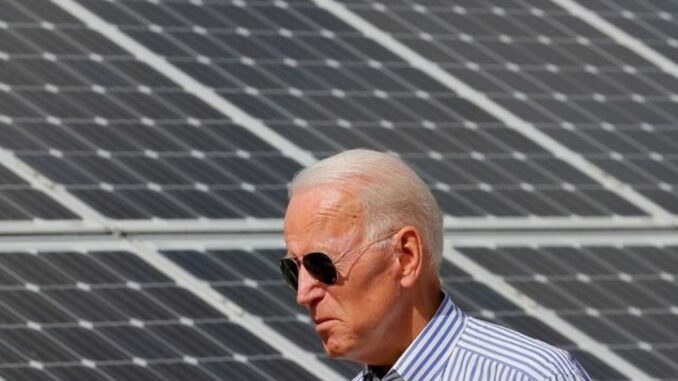

It’s also an early test of the Biden administration’s ability to swiftly implement massive initiatives created under last year’s sweeping climate law — even when it means picking winners and losers.

How the EPA comes down is “the million-dollar question — or, really, the $27 billion question,” said Khalil Shahyd, a managing director of environmental and equity strategies at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

At stake is the fate of an unprecedented effort by the US government to fight climate pollution and environmental injustice at the same time. A successful program could spur the creation of innovative lending arrangements and business models that lure private-sector capital into neglected markets, while bringing the benefits of clean energy to low-income communities.

“At the end of the day, we really want to amplify the expertise that exists, the capacity, the relationships, the financial products and strategies to really be able to effectively deploy this assistance,” said Marissa Ramirez, director of NRDC’s community strategies, environment, equity and justice center.

But there’s little time to waste. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, the agency has only until Sept. 30, 2024 to award grants from the $27 billion fund to deploy zero-emission technologies and carry out other carbon-cutting activities. According to the law, the EPA is supposed to start that process Sunday.

States and tribes are set to get $7 billion. The remaining $20 billion is available for “eligible” nonprofits to provide financial assistance to national, regional, state and local projects, with at least 40% of the funding put to work in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

The law offers little guidance on who those eligible recipients might be. They must be funded by public or charitable contributions and be designed to provide capital or other financial assistance for rapid deployment of low- and zero-emission products, technologies and services. But they can’t take deposits, except for repayments and other revenue tied to the grant program.

Congress left the rest up to the EPA, setting off a scramble by institutions that want the money.

The Coalition for Green Capital, a nonprofit that supports regional green banks, argues it should be the main repository for the $20 billion, making it a nationwide clearinghouse for the funding.

Reed Hundt, the coalition’s chairman, said it is best positioned to maximize investment, with the government’s seed money luring far more private dollars to finance an array of projects and deliver on Congress’ intended benefits.

“The plan here is to maximize leverage with a national entity that can get the greatest amount of investing” so it can be deployed in underserved communities, Hundt told reporters in a December briefing. “If $20 billion were put into a single national entity over the course of a decade, it could cause more than $250 billion of investment.”

Supporters of the approach say the coalition, which does business as the American Green Bank Consortium, can draw on more than a decade of work and across a broad network of state and local partners to ensure money flows to sustainable projects and delivers a bigger carbon-reduction bang for every buck.

“Through the centralized and coordinated green bank model, we can reach the community organizations and the community leaders to activate their networks, to activate their expertise on the ground,” said Michael Jeans, chief executive officer of Growth Opportunity Partners, which provides development capital and services to low-income areas.

Before the IRA’s passage last year, some of the initiative’s biggest congressional champions argued the EPA should use the funding to capitalize a single, nonprofit national financing institution.

But some environmental advocacy groups and local lenders, including credit unions and community development financial institutions, take issue with that approach. Putting all the fund’s eggs in one basket is too risky, they say. The initial grant recipients are a critical gateway for the funding, but a single entity could end up favoring existing relationships and packaging deals in a way that bypasses many of the very communities the law was targeting.

“Concentrating all resources into a single national green bank runs a high risk of excluding community development and green finance intermediates and increases the risk that funds will not be deployed on a timely basis and to the populations the GHGRF is designed to serve,” Michelle Outlaw, with the African-American Credit Union Coalition, told the EPA in written comments.

Critics of the single-entity idea argue that local lenders are better equipped to nurture projects in novel ways, by directly working in the communities they serve to identify opportunities, match building owners with contractors and engineers and even scrutinize the most innovative deals.

The money “will not reach low-income and disadvantaged communities unless funding is provided to financial institutions with specialized expertise in serving them,” said the Rural Community Assistance Corporation, which supports organizations serving low-income people living in the rural West. If the money is distributed widely from the start, “it will allow recipients and their subrecipients to develop customized solutions that truly meet community needs.”

It’s a big balancing act for the EPA and the head of the initiative, Jahi Wise, a former White House climate aide, green bank champion and general counsel of a firm financing electrification projects.

Now, some are advocating a compromise they say offers the best of both worlds: The EPA could steer much of the $20 billion to a national green bank that can lure more private capital and catalyze clean energy ventures with a countrywide reach. The rest could be spread across an array of regional and local organizations, which may have deep experience working in disadvantaged communities but need help building green lending expertise.

The answer may come as soon as next week.

Share This: