The BRICS economic bloc — comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — ended a three-day summit in South Africa on Thursday. It’s not often that a major international conference of national heads of state has one of its leaders wanted on an international arrest warrant for alleged war crimes issued by the International Criminal Court. South Africa is a signatory to the ICC, unlike China, Russia, India and the US itself. In the event, President Putin was content with a remote video speech and having his chief diplomat Sergei Lavrov represent him in Johannesburg along with the leaders of the 4 other bloc members.

The 15th BRICS Summit ended on Thursday with the organization inviting Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAEUAE -0.7% to join as full-fledged members beginning next year. Will this expansion prove historic as part of a plan to “reshape global governance into a ‘multipolar’ world order that puts voices of the Global South at the center of the world agenda”, as Al-Jazeera puts it? Or is it just another media headline prone to melodrama, attaching the term “historic” to any event that would attract a jaded audience bombarded daily with news of some crisis or the other? If the BRICS expansion does prove “historic” in any real sense, just what will this “multipolar” world order look like?

BRIC(S): An Idea Which Did Not Make Money…

The acronym BRIC was coined by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001 for informing investors about a group of rapidly growing emerging markets (Brazil, Russia, India and China) and their potential to challenge the economic dominance of the developed economies of the G-7. The first formal summit of the group was held in 2009, with South Africa joining in 2010 to constitute BRICS. O’Neill’s investment product, the BRIC Fund, was folded in 2015 after it lost 88% of its asset value since a 2010 peak. Evidently, the strategy of bundling four disparate countries into a single investment theme could not deliver returns.

According to the IMF data on GDP measured in PPP international dollars, the BRICS group accounted for just over 31% of global GDP, ahead of the G-7 (just under 31%) in 2020. Within BRICS, China dominates, accounting for almost 60% of the group’s total GDP. India, the world’s third largest economy after China and the US, was next at just under a quarter (23%) of the blocs collective GDP. The shares for the Russian and Brazilian economies (9% and 7%) are much smaller. Intra-BRICS trade was not of particular significance since the bloc’s founding. Since 2014, China has been not only the world’s largest exporter but also the largest trading nation in terms of the sum of its exports and imports. China’s trade relations with the US, EU, Japan and Southeast Asia were far larger and consequential than that with its other BRICS partners.

The BRICS countries are relatively diverse across political, economic and ideological grounds. China’s economic dominance does not translate into a Beijing hegemony over the group. The two largest members of BRICS, China and India, have had frequent border disputes interspersed with lethal flareups over the past several decades. Along with US, Japan and Australia, India is also a member of the “Quad”, an informal forum, seen by some US strategists as a means to contain Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific. In contrast, the G-7 group is relatively homogenous and acts as a geopolitical bloc under a US leadership committed to a “rules-based order” under the Western-dominated Bretton Woods international financial system.

…Until The Russia Sanctions Came Along

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was transformational for the role BRICS played in international trade. After Russia invaded Ukraine, the U.S., U.K., EU and allies imposed the most comprehensive and unprecedented economic attack on a sovereign nation in recent history. At a stroke, Russia became the most sanctioned country in the world. About half of the Russian Central Bank’s foreign exchange reserves held offshore (which totalled over $600 billion) was frozen. Leading Russian banks were also stopped from accessing SWIFT, the international bank payments system. Since February 2022, multiple sanctions have been placed on Russian individuals and institutions, but the focus has been particularly on its main export earners, oil and gas.

As the global energy order rapidly cleaved into two blocs, intra-BRICS trade gained an unprecedented strategic role in the geopolitical tensions brought about by the Russian invasion. Most of the rest of the world outside of the Western alliance did not support the sanctions because they felt, for good reason, that they did not want to be pawns in a global geopolitical rivalry. They also wanted to be able to trade with Russia – a major commodity exporter of fuels, food and fertilizer — according to their needs.

Countries sanctioning Russia overestimated their control of the global energy trade. While Russian exports of coal, oil and natural gas to Europe have fallen sharply since December, these exports have been re-routed to a number of countries. In June 2023, the top destinations of Russian energy exports were, in order, China, India, Turkey, the EU, Brazil and Saudi Arabia. Reflecting the fungibility of energy markets, China re-exported LNG cargoes from Russia to Europe while India exported refined oil products derived from Russian crude oil to world markets.

BRICS+6: Stronger or Weaker?

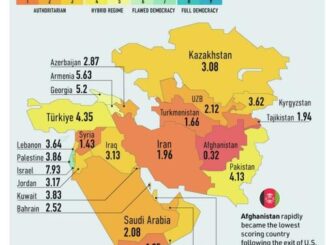

It is by no means clear that all six invited countries will accede as full members of BRICS come January 2024. Argentina’s two leading presidential candidates have outright rejected or cast doubts on such plans although the country’s membership was heralded by Brazil’s President Lula as a positive step. Clearly, the most significant aspect of an enlarged BRICS bloc is the inclusion of three energy heavyweights from the Middle East Gulf: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates. From owning 9% of global oil reserves, the enlarged BRICS+ group will account for 41%; and from producing 20% of global oil production, BRICS plus its three Gulf members would increase the new BRICS+ production share to 42%. Adding to the weight of the Middle East and North Africa region, Egypt is already a major natural gas producer. With new oil and gas discoveries , it will play an increasingly important regional role in energy affairs. Both Egypt and Ethiopia will benefit from access to the BRICS New Development Bank which will have fewer conditionalities than typically imposed by the likes of the World Bank and the IMF.

Both China and Russia welcome the BRICS expansion. The rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, brokered under China’s auspices, was aided by an assertive Saudi foreign policy under Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman. The addition of Iran and Saudi Arabia as well as its Sunni Gulf ally UAE strengthens the role of both OPEC+ and a future BRICS+. Russia will join Saudi Arabia as a key player in both groups. India, reportedly “more cautious” in its approach to BRICS expansion, officially stated that it “fully supports” the expansion. India, like Brazil and South Africa, needs to maneuver its support for BRICS economic integration without alienating a US-led Western alliance that is at ‘proxy’ war with Russia and intent on ratcheting up the rhetoric on containing China in the “Indo-Pacific” region.

Multipolarity And A New World Order

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 signified a unipolar moment to many commentators. The US and its allies stood supreme after the end of the Cold War and “proved” the argument that, in the clash of ideologies between capitalism and communism, capitalism stood supreme. It was ‘the end of history’, as Francis Fukuyama argued. In this view, there was one way towards progress and improvement in material life, and that was to go towards a liberal democratic order, as shown to the world by the US and its allies.

In the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, IMF Economic Counsellor Gita Gopinath stated that “sanctions on Russia could erode the dollar’s dominance by encouraging smaller trading blocs using other currencies”. Zoltan Pozsar, a strategist at Credit Suisse went further in arguing that “We are witnessing the birth of Bretton Woods III – a new world (monetary) order centered around commodity-based currencies in the East that will likely weaken the Eurodollar system…”

However, the widely reported “plans” by China and Russia to introduce a common BRICS currency, backed by commodities or gold, gained little traction in the South African summit. Both China and Russia welcomed trade settlement in national currencies among the BRICS countries as well as others outside the Western alliance. While it has been reported that Saudi Arabia is considering accepting the yuan for its oil exports to China, it is not clear whether this threat to the petrodollar will materialize. On its part, China has little interest in opening its capital account and making its currency freely convertible. Jim O’Neill, the economist who coined the BRIC term, finds ‘de-dollarization’ and the idea of a BRICS common currency to replace the US dollar’s international reserve status “ridiculous” and “almost embarrassing”.

What will the “new world order” look like? For the EU, the loss of access to cheap Russian energy looks irreversible. There will be continued energy demand destruction and de-industrialization, drastic falls in living standards, social strife and the rise of populist parties (such as the AfD in Germany). The US, by the same token, gains comparative advantage in manufacturing over a vassalized Europe with cheaper energy and greater resource endowments. US exports of LNG to Europe, at far higher cost than Russia’s pipeline gas exports, are now an established feature of Europe’s energy balance.

Energy-deficit developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America will face more expensive energy supplies and slower economic growth. They will weigh their own national interests and make their own energy choices. Their choices will not necessarily be cynical and transactional but likely reflect their own attempts to climb the energy ladder that led the West to their current high living standards. For leading developing countries such as Brazil, India, China and South Africa, protecting their freedom to trade with the commodity superpower Russia and other sanctioned states such as Iran is as important as ensuring that they do not become the next victims of a globalizing West wielding its dominance in international financial institutions.

The Ukraine war is a watershed moment in history and the world has changed forever, though perhaps not quite like some would have predicted. It looks less like Fukuyama’s “end of history”, and more like the Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” in the remaking of world order.

Source: Forbes.com

ENB Top News

ENB

Energy Dashboard

ENB Podcast

ENB Substack