Energy News Beat Publishers Note: Outstanding article from the GPF group. Some of the issues not addressed in the article are the financial issues whiting the government causing cash flow issues. They have eliminated some of those with the additional oil field services work with Lybia, and hope to increase further financial independence with the new gas discoveries in the Black Sea.

Turkey’s long-term goal is to become a military and economic power with global outreach. Its path to success, however, isn’t a straight line. Crises will inevitably emerge, requiring tactical pauses or a strategic redirection. Today, Turkey is facing mounting challenges in the international system, forcing the country to rethink its foreign policy. It’s therefore making an effort to stop the deterioration of its foreign relations and to stabilize its financial situation, so that it can resume its quest to become a global power.

Reviving Its Past Glory

Turkey’s claims to great power status have a long history. In the 1930s, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk endorsed the sun language theory – the belief that all languages are derived from an early iteration of the Turkish language. Ataturk, who was a big proponent of Turkish nationalism, wanted to convince European nations that Turkey was one of them. During his time, Turkish historians traced the origins of Turkish nationalism to the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 when the Seljuks defeated the Byzantine army and conquered Anatolia. They emphasized Anatolia’s Hellenistic heritage to advocate that it had a place in Europe.

Like Ataturk, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a populist leader and staunch modernizer. Both men also realized quickly that Russia would not be an ally in Turkey’s quest for greatness. For Ataturk, it was clear that the Soviet model was not one he wanted to follow, and for Erdogan, the two countries’ histories, geographies and perceptions of their own power stood in the way of strategic cooperation. The difference between Erdogan and Ataturk, however, is that Ataturk looked to Europe as a model of modernity that he wanted to replicate in Turkey, whereas Erdogan wants to reconnect Turkey with its Ottoman roots.

Erdogan’s campaign to resurrect Turkey’s past glory and transform it into a military and economic power explains some of Ankara’s recent achievements. Earlier this month, Erdogan announced that Turkey planned to send an unmanned spacecraft to the surface of the moon in 2023. Ankara also plans to launch its first domestic-made communication satellite in 2022.

Over the past two decades, Turkey has developed a robust defense industry that now meets 70 percent of the country’s military equipment needs, with plans to become self-sufficient by 2053. Turkey is one of just 10 countries that manufactures warships and is already working on building a modern main battle tank and a fifth-generation fighter.

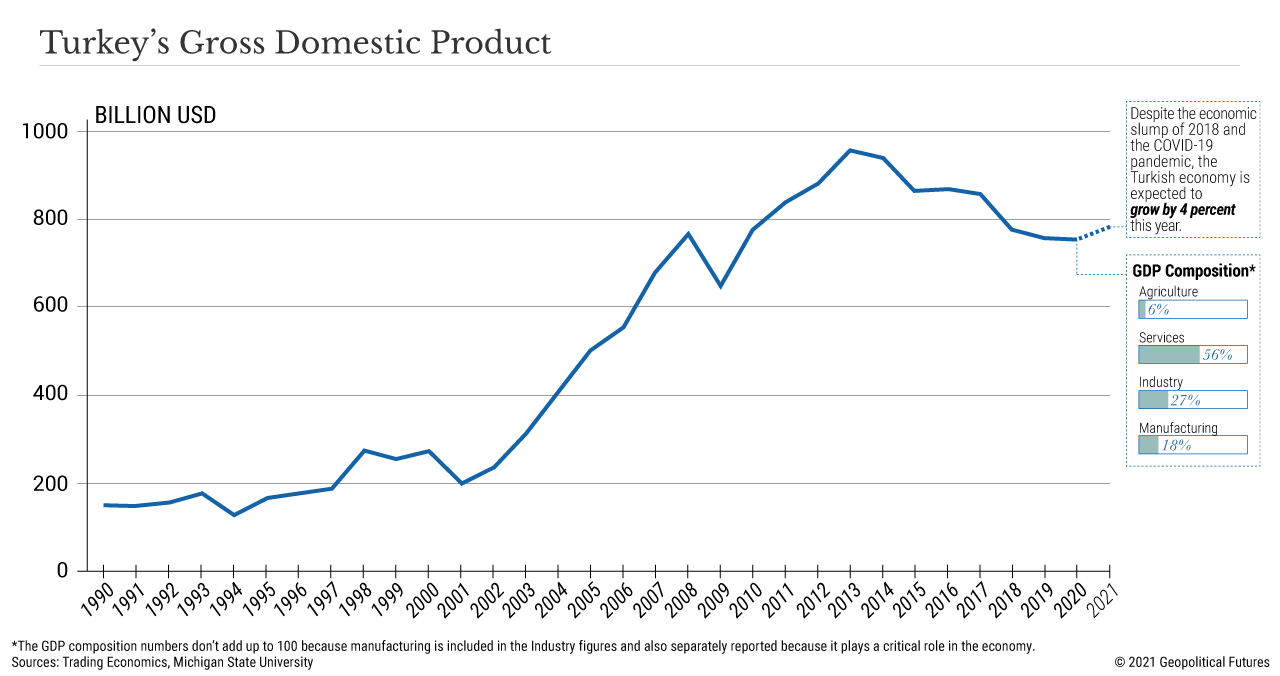

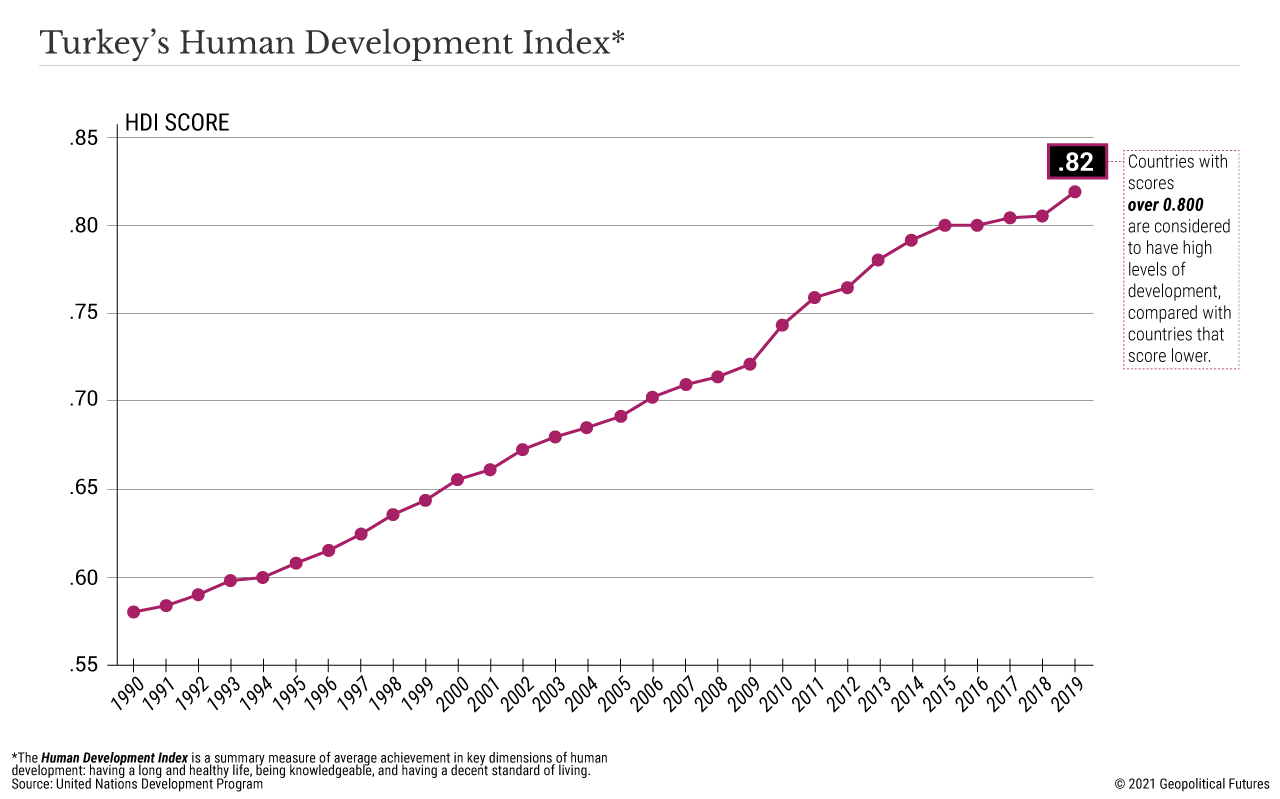

Turkey has also experienced impressive economic development over the past 30 years. Its economy is the world’s 19th largest and 13th largest in terms of purchasing power parity. Its human development index rose from 0.58 in 1990 to 0.82 in 2019, placing it in the very high human development category. It has a modern economic structure, with 65 percent of the labor force involved in the services sector, 27 percent in industry, and 8 percent in agriculture. Despite the economic slump of 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic, the Turkish economy is expected to grow by 4 percent this year.

Recent Foreign Policy Changes

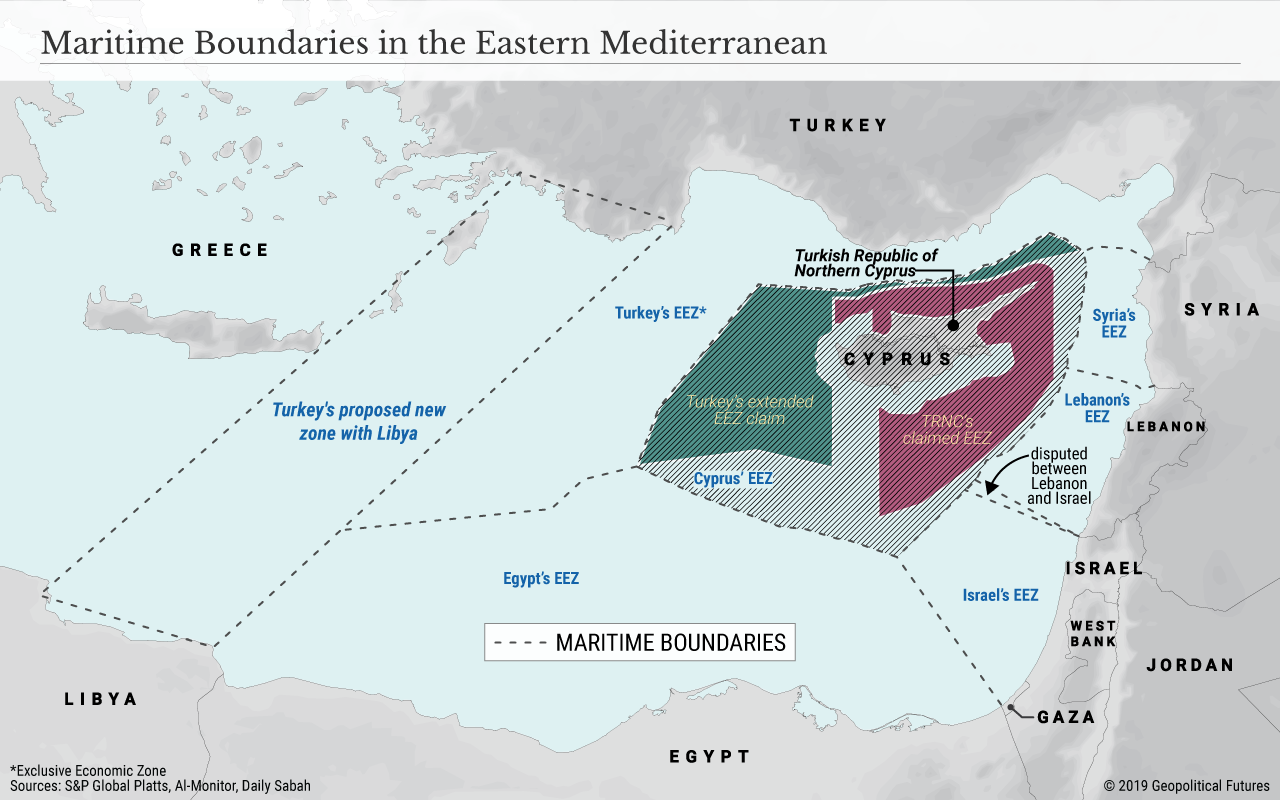

Since the 2016 failed coup, Turkey’s foreign policy has seen a raft of changes. Former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu’s 2004 “zero problems with our neighbors” policy has been replaced with a bewildering array of enemies in the Middle East and beyond. Over the past five years, Turkey has participated in armed conflicts in northern Iraq, Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. It also maintains significant military contingents in Qatar, Northern Cyprus and Somalia. Ankara’s relations with Europe and the United States have deteriorated thanks to its military adventurism, purchase of Russian-made S-400 missiles (which led to a U.S. ban on arms exports to Turkey and Ankara’s expulsion from the F-35 fighter jet program), and recent activities in the Eastern Mediterranean.

However, Turkey appears determined to make 2021 the year of political flexibility and diplomacy. Erdogan is keen on engaging the new U.S. administration – despite President Joe Biden’s calling Erdogan an autocrat during his election campaign and his secretary of state, Antony Blinken, saying that Turkey was not acting as an ally. Erdogan continues to believe that U.S. support for the Syrian Kurds is at the center of the rift between the two countries, but he has softened his tone, signaling that Turkey’s problems with the outside world can be resolved through dialogue. Turkey’s minister of defense also suggested the country was willing not to use the S-400s in an effort to defuse tensions and avoid incurring sanctions.

Erdogan has also expressed an openness to working with Europe. In part, that’s because European leaders already approved sanctions on Turkey over its drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey’s apparent willingness to restart talks with Greece on demarcating exclusive economic zones in the Mediterranean doesn’t change its fundamental position. But the move shows that Ankara would rather use diplomacy than flex its military muscle (which angered NATO, and especially France) to defend its drilling rights in Mediterranean waters. Erdogan has also toned down his criticism of France, after calling French President Emmanuel Macron a thug. Turkey’s foreign affairs minister expressed willingness to start a constructive dialogue with France to resolve their differences on issues ranging from Syria to Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean. Erdogan also urged Europe to remove obstacles blocking its accession to the European Union and European customs union and stalling visa-free entry into the EU for Turkish citizens.

Erdogan has also extended an olive branch to Egypt. Last September, he spoke of the deep historical ties between Turkey and Egypt. He called for dialogue with Cairo and recognized Egypt’s interests in Libya, eager to strike a maritime agreement similar to the one Ankara reached with Libya’s Government of National Accord. Erdogan emphasized that intelligence cooperation between the two countries continued despite their political differences. (Erdogan was a supporter of former Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi, who was ousted in a 2013 military coup led by current President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi.) Turkey has also made overtures to Israel, appointing a new ambassador in December after leaving the post vacant for two years.

Constraints on Policy Shifts

Despite showing room for negotiation on some fronts, Turkey’s position on the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and People’s Protection Units (YPG) remains unshakeable. Ankara views these groups as existential threats because it believes leaving them unchecked could lead to Turkey’s demise. Ankara was angered by the U.S. State Department’s statement earlier this week on the deaths of 13 Turks in Iraq because the statement made its condemnation of the killings contingent on verification that the PKK carried them out – rather than accepting Ankara’s account. That Blinken called his Turkish counterpart to accept the Turkish version of events attests to the Biden administration’s openness to dialogue.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey does not recognize the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea because Ankara believes it favors Greece and Cyprus. Turkey does not expect to reach an agreement with Greece in 2021 to delineate their exclusive economic zones. Though Erdogan is willing to negotiate, he’s not willing to concede much on this issue, which enjoys rare national consensus in Turkey.

With Russia, Turkey has many ongoing disagreements, including over Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. In Syria, Turkey wants an end to Bashar Assad’s regime and a comprehensive political settlement that allows the return of displaced Syrian refugees. In Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkey managed to penetrate Russia’s backyard by backing Azerbaijan’s war to reclaim the disputed region last year. In doing so, it gained access to the Nakhchivan Corridor, linking it to Azerbaijan, as well as Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan via the Caspian Sea.

Future Outlook

Despite its diplomatic overtures, Turkey will face a number of challenges this year. Its relationship with the U.S. will not normalize in 2021, though it’s unlikely to deteriorate any further. Erdogan isn’t willing to burn bridges with an administration that just took office. His most formidable challenge, however, is defining Turkey’s relationship with Russia. Both countries will be bound by dialogue, but their disagreements especially over Syria’s fate will be an obstacle to any rapprochement.

Ankara’s diplomatic outreach may be more successful among its Middle East neighbors. The Saudis, concerned about a shift in Washington’s Gulf policy, especially on Iran and the Houthis in Yemen, seem to have opened up to Turkey to try to secure a semblance of a regional balance. The Saudis are quite interested in allying with Israel, but they cannot do so without the backing of a major Muslim country, such as Turkey. Indicators point to the opening of a new chapter of friendly relations between Riyadh and Ankara. (Turkey also maintains good relations with Qatar, which was the subject of a 3 1/2-year Saudi-led blockade that recently ended.)

Erdogan’s pursuit of an independent Turkish foreign policy sends signals to the West that Turkey will no longer be subservient. In this sense, his foreign policy approach is close to that of Ataturk, who fiercely defended Turkey’s sovereignty and independence. Erdogan is probably the Middle Eastern leader best equipped to seize opportunities when they arise and change his position when circumstances permit, as they do now.

George Friedman’s team at GPF is an outstanding organization – sign up for their paid subscriptions and newsletters to stay current in world politics –geopoliticalfutures.com