Negotiations last week between the United States and Russia say a lot without saying much at all. Talks first took place on Jan. 9 ahead of more official discussions in Geneva the next day. A few days later, Russia and NATO spoke in Brussels about Ukraine and, related, the non-expansion of NATO to the east.

There was never much hope for the negotiations, the top agenda for which was Russia’s proposals for security guarantees, especially vis-a-vis NATO. The three parties ended their talks agreeing only that disagreements remain. After the meetings, the media naturally began to talk about escalation and preparations for an invasion of Ukraine. But this “escalation” looks like a tactic rather than a true position, an attempt by Russia to pressure its adversaries to participate in additional meetings and thus ensure the safety of its precious buffer zones.

Showtime

Even during the negotiations, Russia began to up its psychological pressure on the U.S. and NATO. For example, it initiated military exercises in the western regions of Voronezh, Belgorod, Bryansk and Smolensk – all of them close to the Ukrainian border. (Roughly 3,000 troops participated.) The purpose of the drills was clear: to demonstrate its capabilities and a desire to protect its interests. Psychological operations such as these are particularly important to Moscow, which believes it needs to stand its ground without resorting to war or incurring additional sanctions.

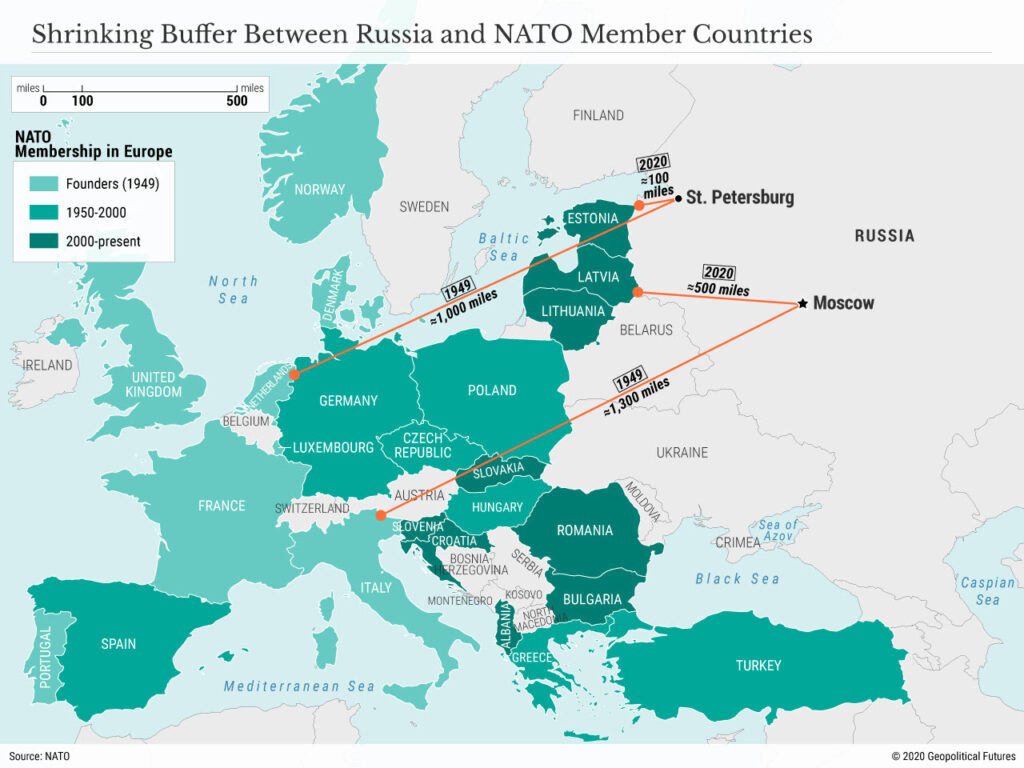

The purpose of Moscow’s demands is also pretty clear. It wanted a guarantee from NATO and Washington that they would not use neighboring countries to prepare for or carry out an armed attack on Russia. It wanted Washington to halt the eastward expansion of NATO, refusing the admission of all former Soviet satellite states. And it wanted assurances that the U.S. would not create military bases in those states, and that NATO would cease military activities in Ukraine as well as other parts of Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Without these guarantees, Russia will inevitably feel vulnerable in its western borderlands. Indeed, one of its most important geopolitical imperatives is to maintain a buffer zone between its heartland and external threats from Europe.

Of course, the Kremlin never expected the U.S. to capitulate to its demands last week. But it had hoped that the West would at least soften some of its stances on these issues. And since the negotiations didn’t go anywhere, we can all expect Russia to act a little more aggressively, if only rhetorically, in the near term. After all, the borderlands remain unsecured: There is a frozen conflict in Donbass, the Caucasus region is constantly challenged by Turkey, and Central Asia is still unstable. In a recent interview with CNN, for example, Russian presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov made several statements that Russia’s relations with NATO are approaching a redline thanks to the alliance’s military support for Ukraine. He went on to say that NATO is a tool of confrontation, that Russia is seeing a gradual NATO invasion of Ukraine, and that proposed U.S. sanctions against Russian leaders could lead to the termination of bilateral relations. Moreover, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, a direct participant in negotiations, said in an interview with RTVI that he cannot rule out the possibility of deploying military assets to Cuba and Venezuela if negotiations with the West fail. Again, this may all be rhetorical, but it nonetheless puts the U.S. on the defensive – and publicly at that.

Aside from heightened rhetoric, Russia has openly stepped up military movements. Over the past week, several dozen videos on TikTok and Instagram have shown the transfer of military personnel and equipment from Siberia and the Far East to Russia’s western regions. Soon thereafter, the Tank Army of the Western Military District began exercises in five regions, in which more than 800 servicemen and more than 300 weapons were involved. Elsewhere, Russian troops began to arrive in southern and western Belarus for exercises. With these moves, Russia intends to send the message that its forces are ready.

Limits

Despite this performative maneuvering, and despite reports of possible strikes, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest neither Russia nor the United States is interested in a serious military confrontation.

First, if Russia wanted a confrontation, it would have done it quietly. Well-advertised military movements, particularly ones involving soldiers from the polar opposite end of the country, surrender any element of surprise Russia could have hoped to have. And though the numbers of troops and tanks in western Russia seem large, they are not nearly enough to wage a winnable war in the vast lands of Ukraine. (Notably, the repositioning of Russian materiel has been underway for nearly a year; it didn’t just start last week.)

Second, deploying weapons or troops to Cuba and Venezuela is no easy task. It would be difficult in the best of times, but these are not the best of times. Bilateral cooperation between them and Russia, for example, is far weaker than it has been in recent years. And in any case, operating in such a remote region requires active movement and reliable logistics to ensure the safety of military installations. The projects will require serious capital investment, which Russia’s unstable economy is not ready for.

Last, the Kremlin can achieve its imperative of securing a buffer zone without resorting to war. For Moscow, a peaceful stabilization in Donbass is a suboptimal but entirely acceptable outcome. Any truce thereto would paint Russian President Vladimir Putin as a peace negotiator who put an end to the frozen conflict, likely raising his approval ratings and world standing. In short, Putin can’t enter a crisis and leave with nothing. The U.S. has even less reason to intervene in a conflict far from its borders with no exit strategy.

Russia wants to appear ready to wage war without losing any leverage at the negotiating table. For its part, the U.S. suspects Russia is probably bluffing. It understands Russia’s limits, and it’s seen this movie before. Russia will continue to conduct operations to try to achieve control over the buffer zone, and the U.S. will be unhappy with those actions, but both sides understand that to ease tensions, they will have to have a dialogue not with the EU, NATO or Ukraine but with each other.