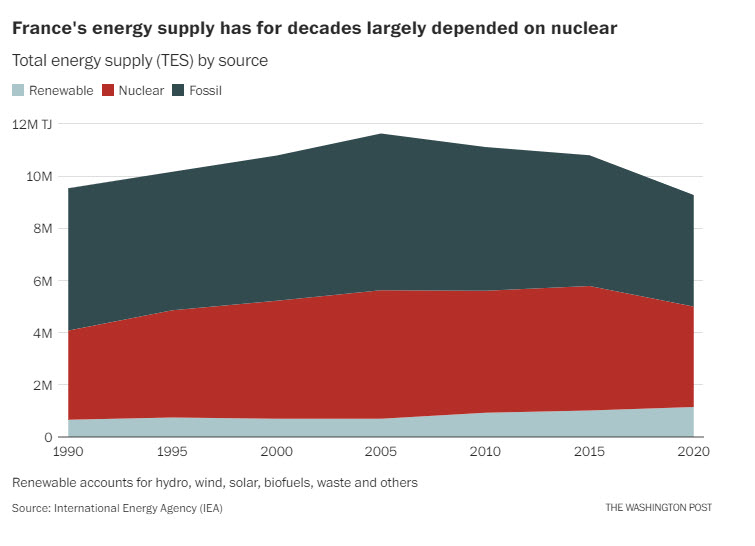

Fessenheim had just begun to come to terms with the closure of its nuclear plant last year, in what the government had said was a “first step” in a “rebalancing” of energy sources. But while Macron remains committed to increasing investments in wind and solar energy, and to putting an end to the burning of coal, his remarks in November confirmed that France isn’t giving up on nuclear technology, its primary source of energy.

Source: Washington Post

Source: Washington Post

Macron’s government argues that investments in nuclear power will allow France to keep energy costs in check, control its own supply and meet its climate goals. France is leading a group of mostly central and eastern European countries that are pushing the European Union to add modern nuclear energy to a list of “environmentally sustainable economic activities.”

In Fessenheim, that has sparked hope that the town — where the power plant supported more than 2,000 jobs — may get a second chance. “We don’t want to be the sacrificed and forgotten ones,” said Mayor Claude Bender, who welcomed Macron’s speech as a “positive surprise.”

But one of the biggest obstacles — for Fessenheim and for Macron’s broader plans — lies about half a mile to the east of the town’s old nuclear plant. That’s where France ends and Germany begins.

The new German economy and climate minister, Green party member Robert Habeck, was among the politicians who signed a statement celebrating the closure of the Fessenheim plant. The German government has argued that nuclear plants are too risky, and too slow and costly to build, to be a solution to the climate crisis. Germany’s outlook is influenced by nuclear accidents, such as the 2011 Fukushima meltdown in Japan. And Berlin points to reports like one this past week, of cracks in the pipes at a French nuclear reactor, as evidence that plant safety remains a problem.

Germany is among a group of skeptics, including Denmark and Austria, that wants Europe to shut down its remaining nuclear plants and that fiercely oppose a climate-friendly designation for nuclear power, which would signal to green investors that nuclear energy is worthy of financing.

The controversy may come to a head within days, with the European Commission expected to make a decision just before its Christmas break.

Perhaps no place symbolizes European divisions on nuclear energy more than Fessenheim.

The 1,800-megawatt nuclear power station here was built in the 1970s — a gigantic white block with two towering reactor-containment buildings, rising from behind a forest outside the town.

On the French side of the border, it was a source of pride, and of economic benefits. The power plant was by far the biggest employer in the area. And taxes from the plant helped subsidize the development of the town, including sports fields, schools and a shopping center.