It’s no secret that international trade is still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the energy and monetary problems both have caused. But a recent episode involving Turkey and its Black Sea trading partners shows how countries are adapting – and struggling to adapt – to these new challenges.

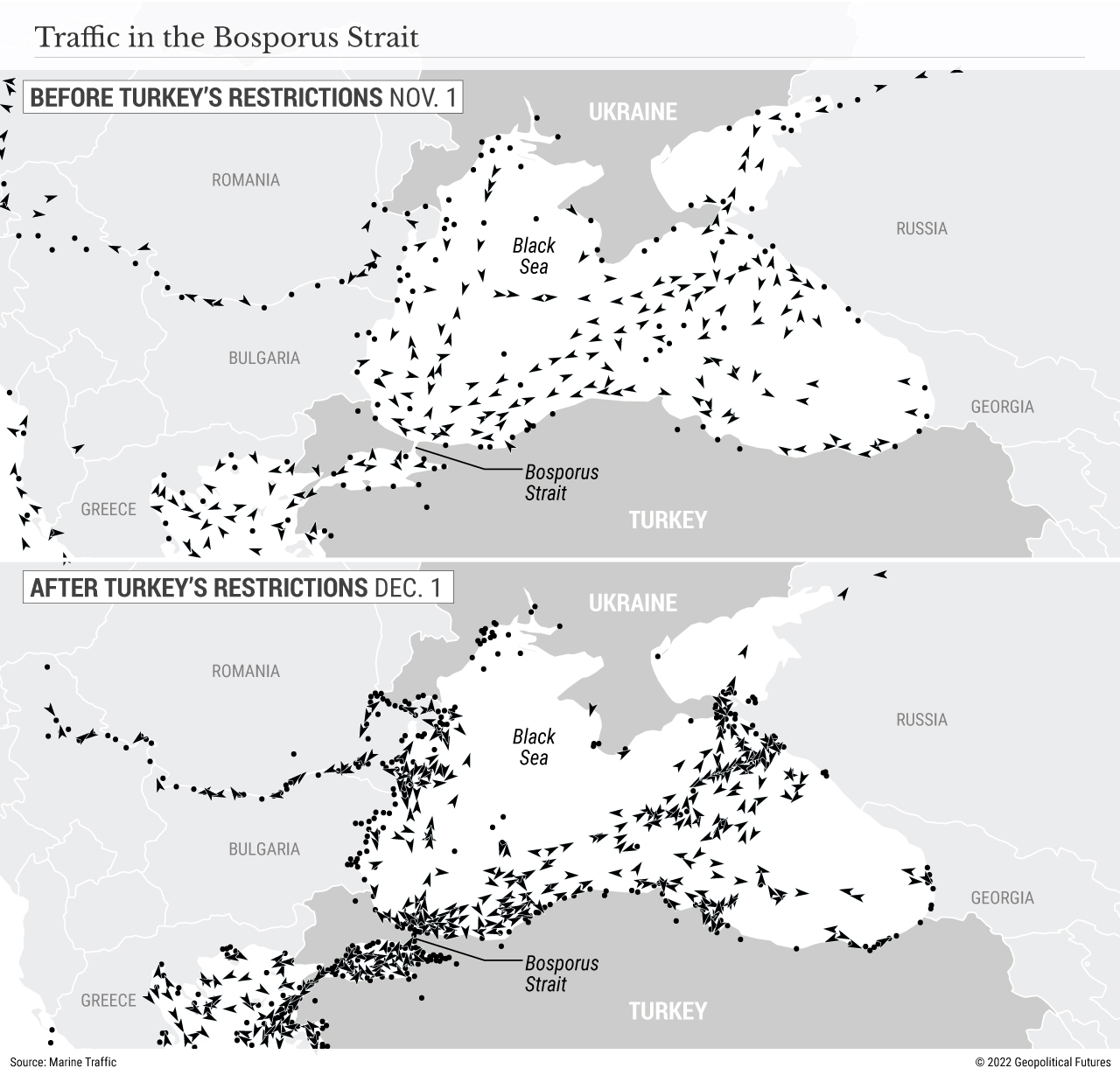

Lloyd’s List, a global shipping publication, reported late Dec. 5 that the G-7 and the EU intervened in negotiations between Turkey and the International Group of Protection and Indemnity Clubs over insurance guarantees, which Ankara had requested for oil shipments passing through the Bosporus strait. Turkey issued a notice two weeks before it implemented restrictions requiring all tankers from Russia and Kazakhstan transiting Turkish waters to provide letters of confirmation from their P&I clubs attesting that insurance coverage will remain in place under any circumstances throughout their stay. (Notably, the notice was issued too late to make it anything but impossible for insurers to comply with.) The measure follows G-7 and EU sanctions that were put in place on Dec. 5 and allow insurance only for Russian oil shipments that have been purchased at or below $60 a barrel. Turkey claims this makes it impossible for port authorities to use conventional insurance verification systems. Ultimately, this has led to congestion in the Black Sea and the Bosporus, creating even more uncertainty in the shipping industry.

To avoid creating more uncertainty in the markets, the G-7 and the EU had awarded a grace period on oil cargoes from Russia that loaded before Dec. 5, while Russia said it would wait until the end of the year to ban companies selling oil using the price cap. Neither the West nor Russia seems to have taken seriously Turkey’s ability to suspend traffic in the Bosporus, a historical source of its regional influence.

Navigating the Water

Since the war in Ukraine started, Turkey has been accommodating both sides, positioning itself as a mediator between the West and Moscow. Before the embargo placed on Russia for its invasion, the EU received about two-thirds of its oil imports from Russia by sea, most of which must first pass through the Bosporus. Put simply, both sides need Turkey, and any threats to hold up traffic in the Bosporus can – and have – concerned Russia and the West.

Geopolitical balancing acts aside, the situation was caused by something Turkey had little to do with: the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions, which have been difficult for businesses to adapt to. This is especially so for companies that did business with both Russia and Ukraine, many of which had to hire consultants to help them navigate the legal waters, as well as companies that depend overwhelmingly on the Black Sea for shipment and delivery.

Unsurprisingly, maritime traffic in the Black Sea dropped dramatically after the war started. Liner shipping services – transporting goods and cargo from one destination to another by ships on a regular schedule – were among the first to fall. Ukraine has been completely cut off from the market since February due to security concerns. Nine out of 10 global container liners have suspended their operations in the Black Sea region. In Russia, liner shipping services were at a loss for all its ports. Before the war, Germany was Russia’s largest partner, with a monthly average of 114 voyages. That number has fallen to 32 since the war began. However, liner business with Turkey remained constant at around 70 voyages per month, and connections with China increased from 29 to 50 voyages.

Cargo ships departing from the northern shores of the Black Sea have also dropped since February. Departures from Ukraine’s ports dropped from 100 per week to 10 per week, recovering only after the Black Sea grain initiative went into effect. (They are still 35 percent below prewar traffic.) Ships departing from Russian ports also decreased. As a result, the number of calls in the Turkish ports dropped as fewer ships going from Ukraine and Russia were looking to pass through the Turkish straits in the first months after the war.

For the rest of the article, please subscribe to GPF HERE. –

Geopolitical Futures is the best place for a total view of critical geopolitical situations.